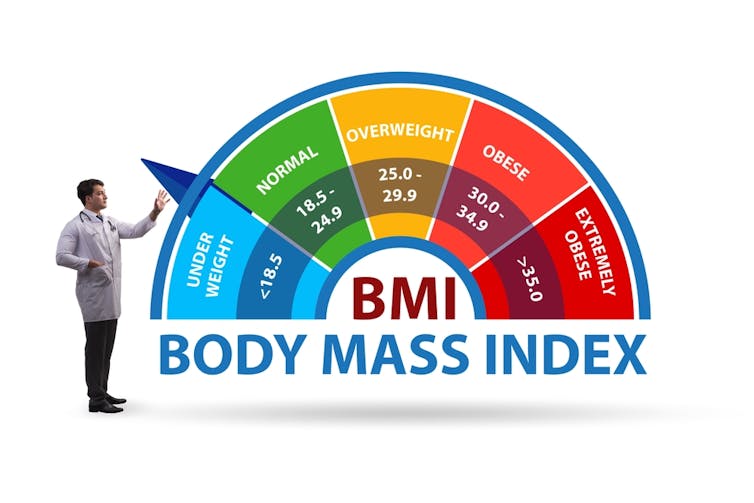

Being slightly overweight might not shorten your life, but being very thin might. A large Danish study tracking more than 85,000 adults has found that people with a BMI below 18.5 were nearly three times more likely to die early than those in the middle to upper end of the so-called “healthy” range.

The link between body weight and health is more complicated than often assumed. This new research, which is yet to be peer reviewed, suggests that the lowest risk of death may not sit neatly in the traditional “healthy” body mass index (BMI) range.

Instead, the findings suggest that people with BMIs that would normally be classed as “overweight” appear to have outcomes that are just as good as, or even better than, those with lower BMIs.

Researchers found a U-shaped curve when plotting BMI against mortality, meaning those with the lowest and highest BMIs were at the highest risk of death.

In the data, presented as a conference paper at the Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, being underweight carried the greatest danger. People with a BMI below 18.5 were nearly three times more likely to die prematurely than those with a BMI between 22.5 and 24.9.

Those at the lower end of the “healthy” range also faced higher risks, with BMIs between 18.5 and 19.9 doubling the likelihood of death. Even people with BMIs between 20 and 22.4 were at a 27% higher risk of an early death compared with the reference group. These findings seem surprising, given that the BMI range of 18.5 and 24.9 is usually considered optimal.

At the other end of the scale, carrying extra weight did not always translate into greater risk. In the study, people with BMIs between 25 and 35 (typically categorised as “overweight” or “obese”) showed no significant increase in mortality compared with the reference group.

Only those with a BMI of 40 or more saw their risk of death rise substantially, more than doubling (2.1 times).

These findings add further data that challenges the common societal association between thinness and health. But research shows that being underweight is a risk to health, particularly in older age.

Having some fat reserves can help the body cope with illness. For example, patients undergoing cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy, tend to lose weight due to factors such as appetite loss and changes to taste.

Those with more fat reserves at the start can draw on them, helping their bodies continue essential functions. In contrast, someone with very little fat may run out of reserves quickly, limiting their body’s ability to recover.

Unintentional weight loss is also often a warning sign of illness, with conditions such as cancer and type 1 diabetes often resulting in weight loss before diagnosis. This means a low BMI can sometimes be a marker of underlying disease.

Not surprising

Following on from the researchers’ conference paper, there have been headlines such as: Being too thin can be deadlier than being overweight, Danish study reveals. That might sound surprising, but it shouldn’t. We need food to survive, and without it, we will die. We know this, and have known this for hundreds, if not thousands of years.

Without food, the body enters a catabolic state, where it breaks down tissues to get the energy needed to keep the brain functioning. In this process, other important body functions, such as immune function, are put on hold to prioritise energy for the brain.

It is worth noting that the Danish participants in this study had all undergone body scans for health reasons. These scans are costly, so they are usually carried out for a good reason – when a health issue is suspected.

The researchers acknowledge that a possible reason for their findings is that participants could be losing weight due to an underlying illness, and so it could be the illness itself, rather than the associated weight loss that is increasing the risk of death.

Still, the findings reinforce what other research has suggested: thinness is not always protective, and extra weight is not always harmful. The concept that you can be “fat but fit” continues to gain scientific backing.

Does this mean the “healthy” BMI range should be revised upward? The researchers suggest this, saying that modern medical advances, which help people manage obesity-related conditions such as diabetes and heart disease, could be shifting the safest weight range higher than before. A BMI between 22.5 and 30 may now carry the lowest risk of death, at least in the Danish population studied.

Elnur/Shutterstock.com

A blunt tool

The trouble is, BMI has always been a blunt tool, as I have previously argued. It doesn’t take into account important factors for health, such as diet, lifestyle, and fat distribution, among others.

BMI can be misleading for people from different racial, ethnic, or cultural backgrounds. Critics say the standard cutoffs are based on white body types, which can make perfectly healthy bodies from other groups seem “unhealthy”.

Indeed, BMI was developed nearly two centuries ago using data from a small sample of white, European men. Although some efforts have been made to adapt ranges for certain ethnic groups, for example, NHS guidance lowers the BMI thresholds for increased risk of diabetes in Asian and black groups, BMI still fails to account for differences in body composition, fat distribution and baseline risk among individuals in our diverse society.

When significant healthcare decisions – such as access to fertility treatments and certain surgeries – are based on BMI, we should expect it to be an accurate and fair measure, developed and validated in populations that truly represent the people it is applied to.

Read more:

Why you can’t judge health by weight alone

In an ideal world, healthcare professionals would have access to more detailed measures such as blood tests, imaging scans, and detailed lifestyle information. These are costly and time consuming, but they reveal much more than a height-to-weight ratio ever can. Until better measures are widely available, BMI will continue to be used, but studies like this underline the need to refine how it is interpreted.

The Danish data is still preliminary. More details and further research will be needed before drawing firm conclusions. But the headline message stands: being very thin is dangerous, and carrying some extra weight may not shorten life. The real lesson is not that thin is bad and fat is good, but that BMI alone is a fragile measure of health.

Source link