More than 10 million people worldwide are living with Parkinson’s disease, a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that leads to symptoms such as tremors, slow movement, limb stiffness, and balance issues. Scientists still don’t know what causes the disease, but it’s thought to develop due to a complex mixture of genetic and environmental factors, and treatment is still quite limited.

But new research is putting scientists one step closer to some possible answers.

In a recent study published in JCI Insight, researchers found a common virus, called human pegivirus (HPgV), in the brains of patients who had Parkinson’s disease when they died. Although HPgV infections don’t usually cause symptoms, researchers believe the virus may be playing a role in the development of Parkinson’s.

“The hypothesis is that a long-term, low-burning infection might lead to these sorts of diseases,” such as Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders, says Barbara Hanson, a researcher at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, and one of the authors of the paper.

Here’s what we know so far.

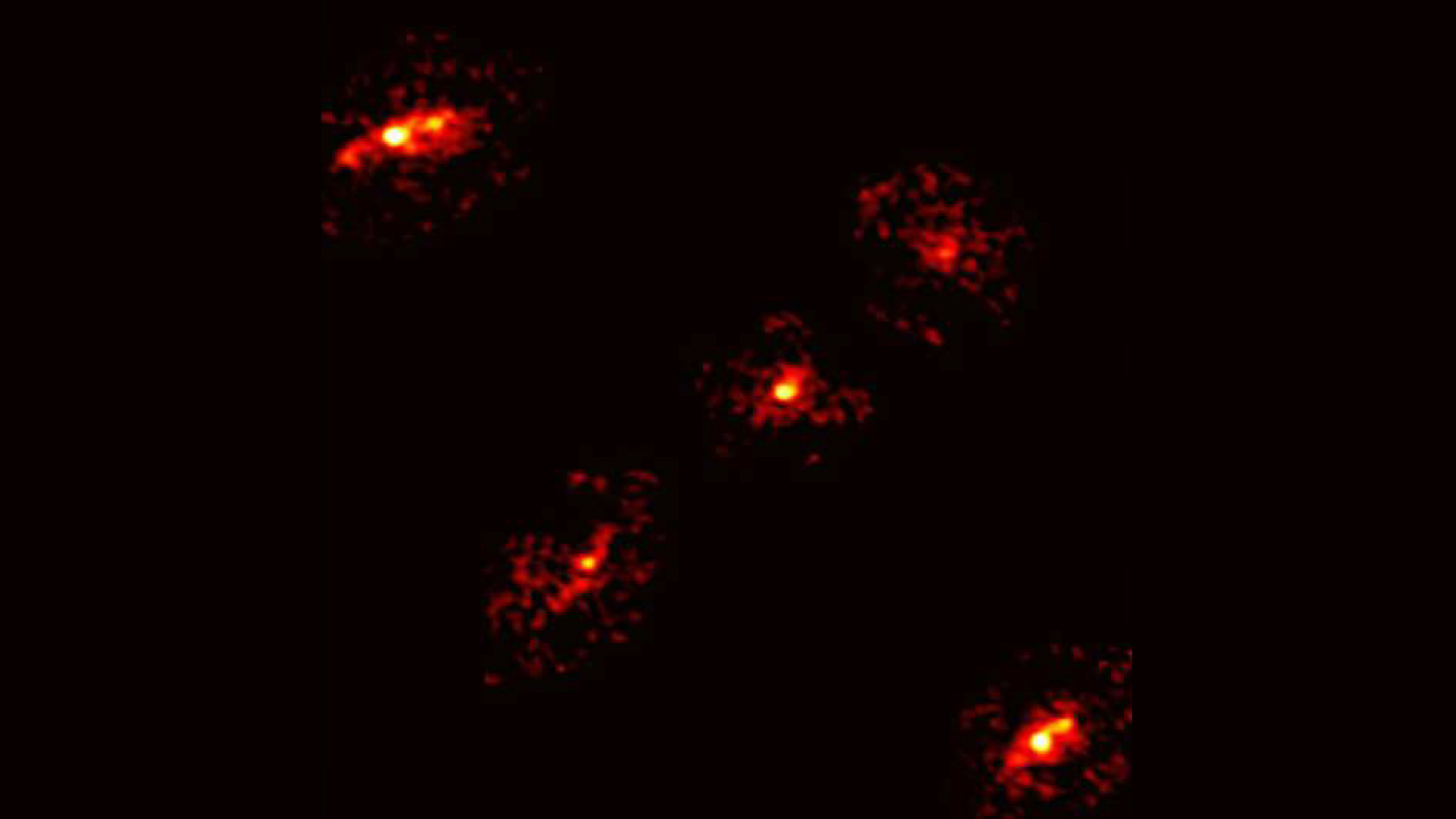

Colored Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan showing the brain of a 65-year-old patient with Parkinson’s. New research suggests that viral infections can be at play in the development of the disease. Photograph by Zephyr/Science Photo Library

Over 500 viruses screened

In this study, researchers screened for over 500 viruses in the autopsied brains of 10 patients who had Parkinson’s disease and compared them to the autopsied brains of 14 control patients, who were matched for age and gender. In five of the patients with Parkinson’s, they found the presence of HPgV, while none of the control patients had the virus.

In order to bolster their findings, researchers conducted follow-up experiments that looked at the blood samples of patients who were in different stages of Parkinson’s disease. What they found was that patients who had Parkinson’s and were positive for HPgV had similar immune system responses, including a lower level of an inflammatory protein called IL-4, which can either promote or suppress inflammation depending on the situation.

They also found that patients who had a specific Parkinson’s-related gene mutation had a different immune system response to HPgV, compared to patients with Parkinson’s who didn’t have the mutation. “It was a very thorough study,” says Margaret Ferris, a neurologist and researcher at Stanford University who was not part of the study. She adds that this offers a possible mechanism for the interaction between genetics and environment.

Why Parkinson’s disease is so hard to study

Although the presence of HPgV in the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease is suggestive of a link, the full answer of what causes the neurodegenerative disease is more complex.

Parkinson’s disease has always been hard to study, due to the fact that it develops slowly, over many years, and is difficult to diagnose in the earlier stages. “One of the hard things about investigating neurodegenerative disorders is that it is very hard to identify people who will get neurodegenerative disorders, but don’t yet have them, and to study and watch them,” Ferris says.

Further complicating this matter is the fact that there doesn’t seem to be one single trigger for Parkinson’s disease. “It is difficult to determine the causes of Parkinson’s, because they are likely multifactorial,” says William Ondo, a neurologist at Houston Methodist Hospital, who specializes in treating patients with movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease. Ondo was not part of the study.

Currently, Parkinson’s disease is believed to develop from a complex mixture of genetic and environmental factors, with individual triggers varying from one person to another. This makes studying the potential causes of the disease quite challenging, and means that there still aren’t definitive answers to what can trigger the condition. It’s likely that some people may develop Parkinson’s disease as a result of multiple triggers.

“Everyone is on their own path,” to developing Parkinson’s disease, says Erin Furr-Stimming, a neurologist at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston, who was not part of the study.

Link between viral infections and neurodegeneration

In recent years, there has been a growing body of evidence to suggest a link between viral infections and the development of neurological diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s. This includes the recent discovery that Epstein-Barr virus is a major trigger for multiple sclerosis, as well as a number of associations between viral infections and neurodegenerative conditions. Parkinson-like symptoms have also been triggered by a number of viral infections, such as West Nile virus, St. Louis Encephalitis virus, and Japanese Encephalitis B Virus.

As Hanson notes, inflammation in the brain has been linked to the development of neurodegenerative disorders, with viral infections being a potential trigger for this inflammation.

“Any amount of inflammation in the brain can trigger a number of cascades that lead to the loss of normal homeostatic brain function,” Hanson says. “It’s possible that viral infections are one of those triggers that lead to inflammation in the brain.” Other potential reasons that viral infections may lead to neurodegeneration include direct damage to neurons from the virus, or the accumulation of misfolded proteins.

However, while this recent study offers evidence of a suggested link between HPgV and the development of Parkinson’s disease, there’s still more research needed before a clear link between the two can be established.

“This study doesn’t show a cause-and-effect relationship—it just suggests there may be a relationship between pegivirus and Parkinson’s,” says Joseph Jankovic, a neurologist and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Center and Movement Disorders Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine. In order to understand the connection further, Jankovic says, “this study needs to be replicated in a different cohort of patients.”

Source link