Imbibing even the smallest amounts of booze can raise your risk of dementia, according to the largest combined observational and genetic study to date on the subject.

The findings counter previous research showing that light-to-moderate drinking might protect against cognitive decline.

The international team of researchers behind the new study suggests that cutting out drinking altogether may be the best way to minimize the risk of dementia later in life, with increasing levels of alcohol consumption matching an increasing likelihood of developing dementia of any kind.

“Our study findings support a detrimental effect of all types of alcohol consumption on dementia risk, with no evidence supporting the previously suggested protective effect of moderate drinking,” write the researchers in their published paper.

Related: There Is No Safe Level of Alcohol Consumption, US Surgeon General Warns

The team began by looking at 559,559 adults in the UK and US, aged between 56 and 72 at the start of the study period. The participants filled out questionnaires on their drinking habits, and their health was monitored for up to 15 years afterwards.

This part of the research resulted in a classic U-shaped graph: non-drinkers and heavy drinkers were shown to have the highest risk of dementia. That fits in with some earlier research, and appears to suggest that moderate drinking is associated with the lowest dementia risk.

But the researchers argue that the protective effect of light drinking doesn’t actually exist – that non-drinkers are often heavy drinkers who have quit, or who have cut down on booze because of the early effects of cognitive decline. In other words, the stats are skewed.

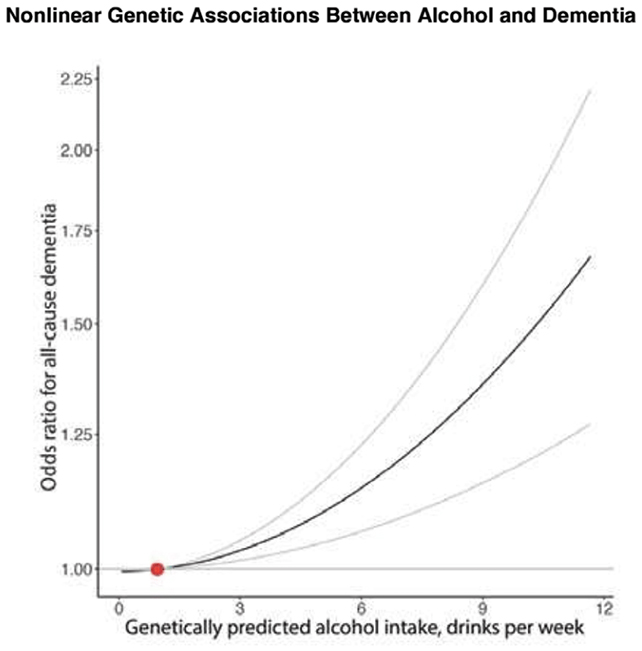

To find more evidence, the study also looked at genetic records for 2.4 million people, using Mendelian randomization to analyze drinking in relation to dementia. The approach works by using a genetic predisposition to drinking rather than data on actual drinking habits – which in theory cuts out other factors, such as lifestyle or wealth.

In this part of the analysis, the U shape disappeared. The higher the predicted alcohol consumption, the higher the dementia risk, with no dip for light drinkers who enjoyed the occasional beer or glass of wine.

“Halving the population prevalence of alcohol use disorder may reduce dementia cases by up to 16 percent, highlighting alcohol reduction as a potential strategy in dementia prevention policies,” write the researchers.

There are some significant caveats to consider, which the researchers openly acknowledge. In the first part of the study, drinking habits were self-reported by the participants, not scientifically observed, which can lead to inaccuracies.

In the second half of the study, Mendelian randomization is a useful tool, but relies on linking genetic data to the likelihood of a trait – in this case, that someone drinks. It’s not a direct record of alcohol intake.

However, given the extensive scope of the research and the multiple previous studies that it adds to, it’s solid evidence that as we drink more, the chances of cognitive decline and dementia in later life go up.

“Neither part of the study can conclusively prove that alcohol use directly causes dementia,” says neuroscientist Tara Spires-Jones, from the University of Edinburgh in the UK, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“But this adds to a large amount of similar data showing associations between alcohol intake and increased dementia risk, and fundamental neuroscience work has shown that alcohol is directly toxic to neurons in the brain.”

The research has been published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

Source link