An international team led by Weizmann Institute of Science and Northwestern University scientists says it has discovered a never-before-seen core of a supernova, a massive exploding star, that was rich in heavy elements such as silicon, sulfur and argon.

The star’s outer layers were stripped away suddenly, and the blazing inner core — the heart of the massive star, dubbed SN2021yfj — was revealed before the explosion.

“We now have evidence that there are heavier elements inside stars,” Prof. Avishay Gal-Yam, head of the experimental astrophysics group at the department of particle physics and astrophysics at Weizmann, told The Times of Israel. “We know the sun contains mostly hydrogen and we theorized that stars had heavier elements. But this is the first time we have evidence.”

Dr. Ofer Yaron, a staff scientist in Gal-Yam’s group and a leading expert on supernova databases, also participated in the study, with lead author Dr. Steve Schulze, a former member of Gal-Yam’s team at the Weizmann Institute and currently a researcher at Northwestern University, along with researchers from France, Italy, China and Ireland.

The findings, published Wednesday in Nature, were featured on the cover.

The discovery comes two months after a devastating Iranian missile attack on Weizmann, a world-leading research institute in Rehovot. Nobody was killed but the strike destroyed around 45 labs, some containing researchers’ entire life’s work, which might take years and tens of millions of shekels to rebuild.

“Fortunately, the physics faculty was spared,” Gal-Yam said.

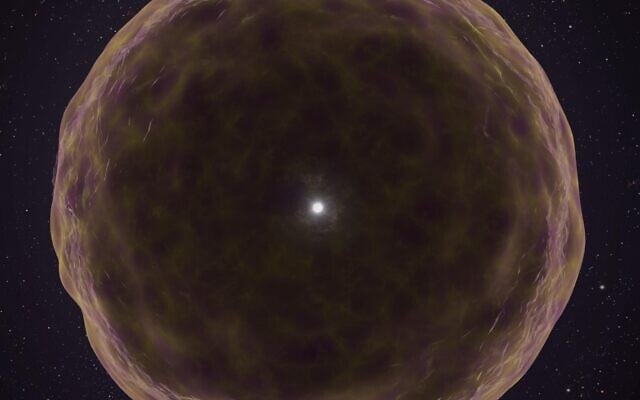

An artist’s depiction of the most likely scenario for SN 2021yfj . Near the end of its life, the dying star underwent two rare, extremely violent episodes, ejecting shells rich in silicon (gray), sulfur (yellow) and argon (purple). These massive shells collided with one another violently, creating a particularly brilliant supernova that could be seen from a distance of 2.2 billion light years. (Courtesy/Keck Observatory/Adam Makarenko)

Flare spotted 2.2 billion light-years from Earth

Massive stars can weigh from ten to 100 times more than our Sun. Despite their immense dimensions, however, they collapse within a fraction of a second. But the bright light emitted in the explosion can usually be observed for several weeks.

Schulze and colleagues discovered the flare of SN2021yfj in September 2021, using the Zwicky Transient Facility, a telescope located east of San Diego, California, which is equipped with a wide-field camera to scan the entire visible night sky. After looking through the telescope’s data, Schulze spotted an extremely luminous object in a star-forming region located 2.2 billion light-years from Earth.

To gain more information about the mysterious object, Schulze and his team wanted to obtain its spectrum, breaking down dispersed light into component colors, each of which represents a different element. By analyzing a supernova’s spectrum, scientists can determine which elements are present in the explosion.

Schulze was unable to find a spectrum, however. Telescopes around the globe were either unavailable or could not penetrate the clouds to obtain a clear image. Finally, a colleague at University of California Berkeley provided the required spectrum data.

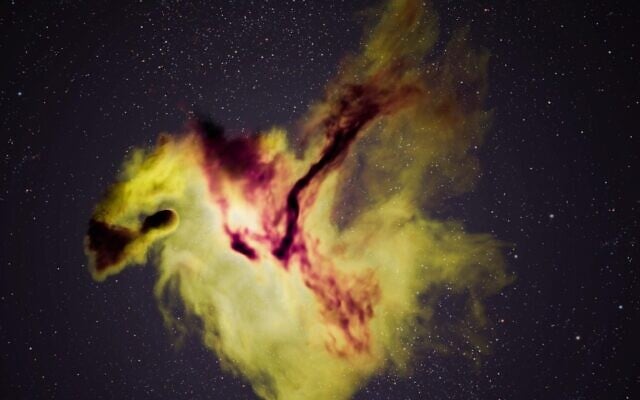

The explosion left behind an interstellar gas-and-dust cloud rich in silicon (gray), sulfur (yellow) and argon (purple) of star SN2021yfj in September 2021. (Courtesy/Keck Observatory, Adam Makarenko)

Surprising findings about this ‘stripped’ star

Soon after Schulze examined the spectrum, he contacted Gal-Yam, who has worked with him for about ten years, Gal-Yam said, to “try to figure it out.”

“I identified silicon, sulfur and argon within a few hours,” Gal-Yam said. “It was obvious we were witnessing something no one had ever seen before.”

Supernovas are caused by aging massive stars literally tearing themselves apart. As a star’s core is squeezed under its own gravity, it becomes even hotter and denser. The extreme heat and density then reignite nuclear fusion with such incredible intensity that it causes a powerful burst of energy that pushed away a star’s outer layers.

Massive stars typically shed layers before exploding. Earlier observations of “stripped stars” revealed layers of helium or carbon and oxygen, exposed after the outer hydrogen envelope was lost. But the SN2021yfj ejected far more outer layers, enabling the scientists to peer deeper into the star’s core and detect heavier elements.

“This star lost most of the material that it produced throughout its lifetime,” Schulze said. “So we could only see the material formed during the months right before its explosion. Something very violent must have happened to cause that.”

Artist’s drawing of SN 2021yfj. Having lost its outer layers, the dying star was left with only a core of oxygen, sulfur and silicon (bright center dot) but continued to experience extreme mass loss episodes that led to the ejection of material rich in silicon, sulfur, and argon. (Courtesy/ Keck Observatory/Adam Makarenko)

The team of scientists hypothesize that the supernova might have been influenced by a potential companion star, a massive pre-supernova eruption, or even unusually strong stellar winds.

”Peering into the depths of a giant star expands our scientific understanding where the heavy elements come from,” Gal-Yam said.

“Every atom in our bodies and in the world around us was created somewhere in the universe,” he said. “It went through countless transformations over billions of years before arriving at its current place, so tracing its origin and the process that created it is incredibly difficult.”

Gal-Yam said his research group will continue to focus on exploring how elements are formed in the universe.

“It’s always surprising – and deeply satisfying – to discover a completely new kind of physical phenomenon,” he said.