Humanity’s war against drug-resistant microbes is not going very well.

Antibiotic resistance has rapidly become one of our species’ leading causes of death, claiming an estimated 5 million lives globally in 2019. That already exceeds the yearly death toll from HIV/ AIDS or malaria, and the danger of drug-resistant infections is only expected to grow.

According to a new study, these so-called superbugs can also be alarmingly prevalent in newborn babies, to the point that frontline treatments for sepsis are no longer effective against the majority of bacterial infections.

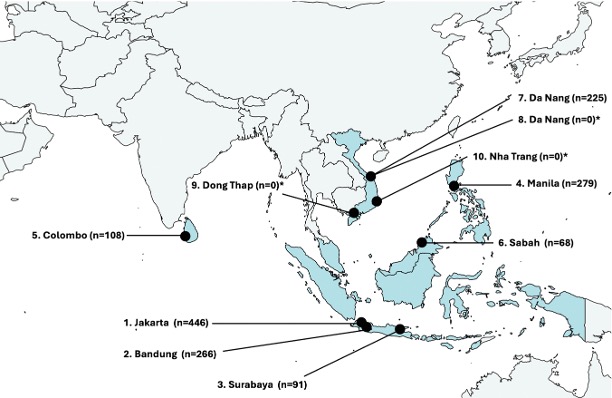

Researchers focused on Southeast Asia for the new study, analyzing nearly 15,000 blood samples collected from sick infants at 10 hospitals across five regional countries in 2019 and 2020.

Related: A Hidden Threat Looming Behind Antibiotic Resistance Is Now Emerging

Most infections they found involved bacteria unlikely to be subdued by standard treatments. The study revealed high rates of non-susceptibility to commonly prescribed antibiotics recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for neonatal sepsis.

At the 10 hospitals covered in this study, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was ominously common among disease-causing bacteria, says study co-author Phoebe Williams, a pediatrician at the University of Sydney.

“Our study highlights the causes of serious infections in babies in countries across Southeast Asia with high rates of neonatal sepsis, and reveals an alarming burden of AMR that renders many currently available therapies ineffective for newborns,” Williams says.

“Guidelines must be updated to reflect local bacterial profiles and known resistance patterns,” she adds. “Otherwise, mortality rates are only going to keep climbing.”

The situation is compounded by the dearth of new antibiotics in development for babies, says co-author Michelle Harrison, a PhD candidate at the University of Sydney School of Public Health, coordinating the research consortium that published the study.

“It takes about 10 years for a new antibiotic to be trialled and approved for babies,” Harrison says. “With so few new drug candidates in the first place, we need a significant investment in antibiotic development.”

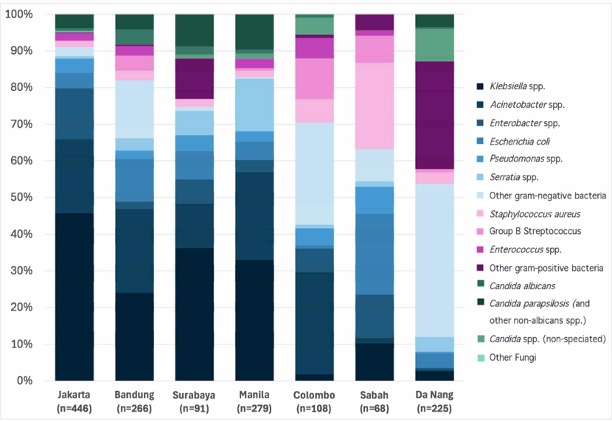

The study found a preponderance of Gram-negative bacteria causing infections in newborns at these hospitals. Due to the structure of their cell envelope, Gram-negative bacteria have an in-built resistance to some antibiotics, and are generally more likely to develop antibiotic resistance than Gram-positive species.

The distinction arises from their different responses to the Gram staining test, which is used to divide bacterial species into these two broad groups based on properties of their cell walls.

Abundant Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli, Klebsiella, and Acinetobacter were responsible for nearly 80 percent of infections studied, the authors report.

“These bugs have long been considered to only cause infections in older babies, but are now infecting babies in their first days of life,” Williams says.

The urgency of neonatal sepsis rarely allows time for lab tests to pinpoint the culprit, so doctors often make educated guesses guided by published research. Much of that research comes from high-income countries, however, limiting its helpfulness in many parts of the world.

These findings highlight the need for more locally relevant data to help doctors quickly identify which treatments are most likely to work, the researchers say.

“We need more region-specific surveillance to guide treatment decisions. Otherwise, we risk reversing decades of progress in reducing child mortality rates,” Harrison says.

“Our results also revealed fungal infections caused nearly one in 10 serious infections in babies – a much higher rate than in high-income countries,” Harrison adds. “We need to ensure doctors are prescribing treatments that have the best chance at saving a baby’s life.”

The study was published in the Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific.

Source link