Summary: New research reveals that primates with longer thumbs tend to have larger brains, suggesting that manual dexterity and brain evolution developed together. The study analyzed 94 living and extinct primate species and found a consistent link between thumb length and brain size.

Surprisingly, the growth was tied to the neocortex — the region linked to higher thinking — rather than the cerebellum, which controls movement. This provides the first direct evidence that the evolution of precise gripping and cognition were tightly intertwined.

Key Facts:

- Thumb-Brain Link: Longer thumbs correlate with larger brains across primates.

- Neocortex Connection: Growth was tied to cognition and sensory processing, not movement control.

- Evolutionary Insight: Dexterity and intelligence evolved together, shaping human uniqueness.

Source: University of Reading

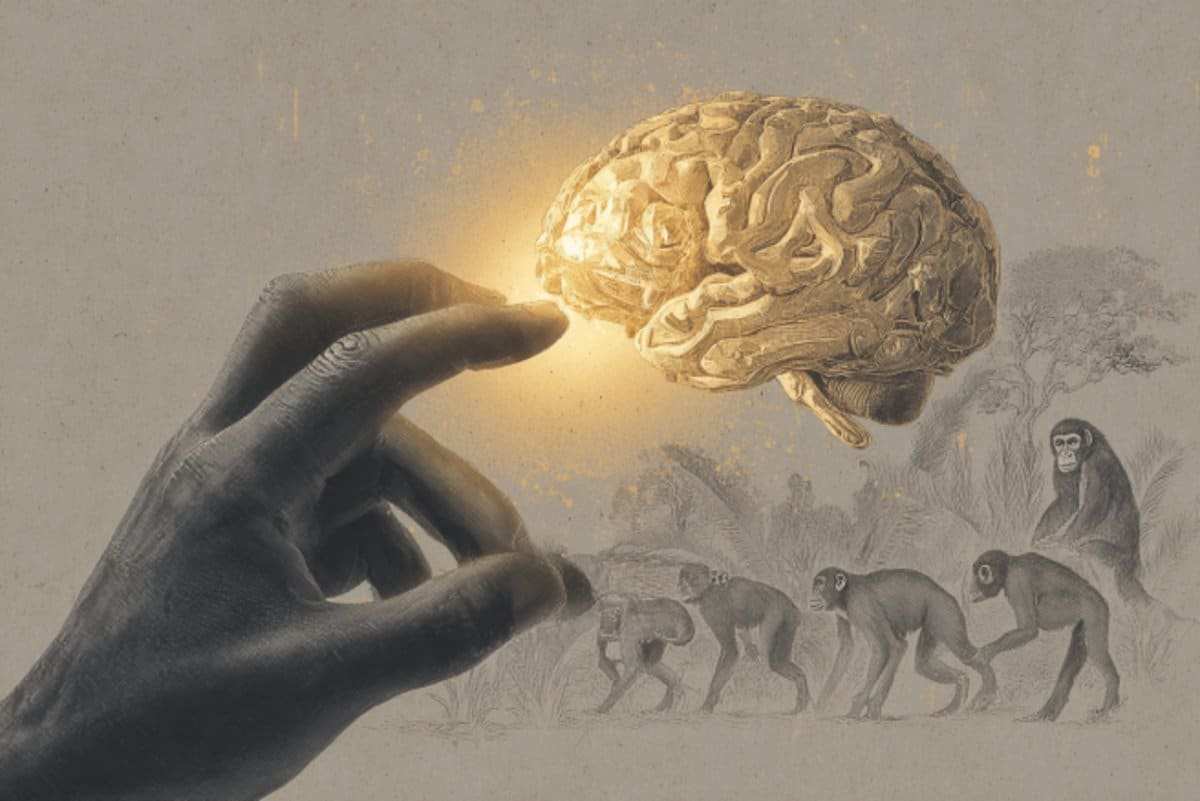

Longer thumbs mean bigger brains, scientists have found – revealing how human hands and minds evolved together.

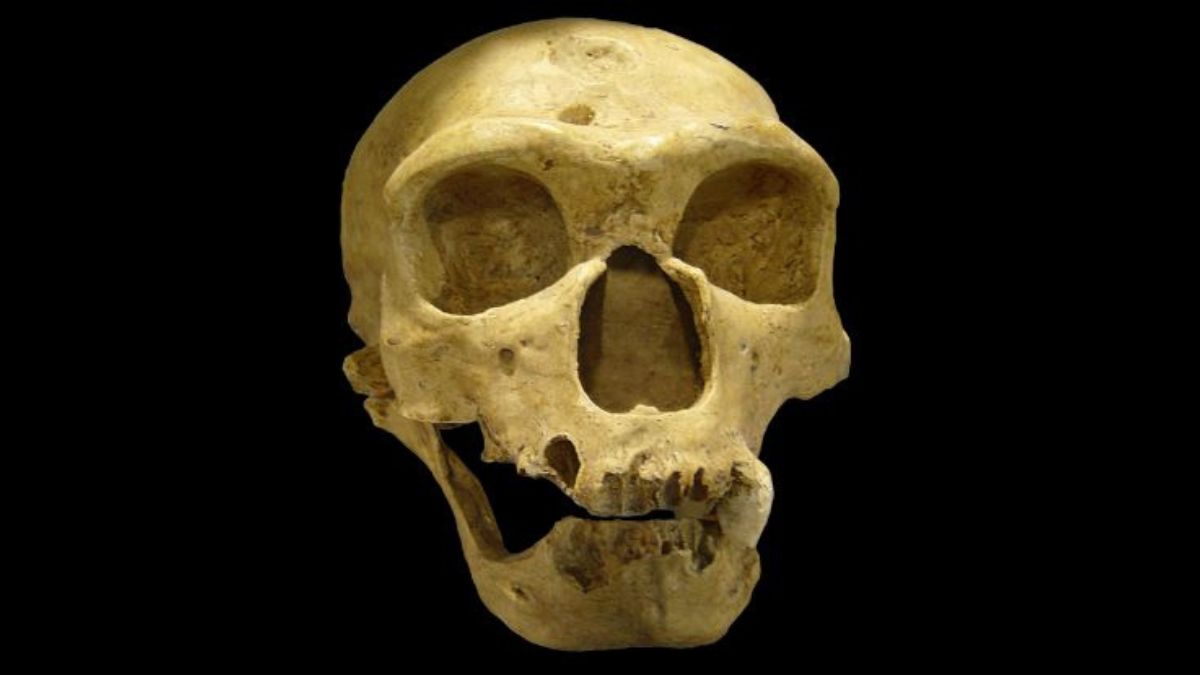

Researchers studied 94 different primate species, including fossils and living animals, to understand how our ancestors developed their abilities.

They found that species with relatively longer thumbs, which help with gripping small objects precisely, consistently had larger brains.

The research, published today in Communications Biology, provides the first direct evidence that manual dexterity and brain evolution are connected across the entire primate lineage, from lemurs to humans.

Humans and our extinct relatives boast both extraordinarily long thumbs and exceptionally large brains. However, the link remains strong across all primates: when scientists removed human data from their analysis, the connection between thumb length and brain size remained.

Dr Joanna Baker, lead author from the University of Reading, said: “We’ve always known that our big brains and nimble fingers set us apart, but now we can see they didn’t evolve separately.

“As our ancestors got better at picking up and manipulating objects, their brains had to grow to handle these new skills. These abilities have been fine-tuned through millions of years of brain evolution.”

Thumbs linked to thinking, not movement

The scientists made a surprising discovery about which part of the brain grows alongside longer thumbs. They expected longer thumbs to be linked to the cerebellum because it is the region of the brain that controls movement and coordination.

Instead, longer thumbs were connected to the neocortex (a complex layered region comprising approximately half the volume of the human brain), which processes sensory information and handles cognition and consciousness.

It was a surprise that only one of the two major brain regions they thought would be involved actually was.

The findings suggest that as primates developed better manual skills for handling objects, their brains had to grow to process and use these new abilities effectively – but further work is needed to establish exactly how the neocortex supports manipulative abilities.

About this neuroscience and evolution research news

Author: Ollie Sirrell

Source: University of Reading

Contact: Ollie Sirrell – University of Reading

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Human dexterity and brains evolved hand in hand” by Joanna Baker et al. Communications Biology

Abstract

Human dexterity and brains evolved hand in hand

Large brains and dexterous hands are considered pivotal in human evolution, together making possible technology, culture and colonisation of diverse environments.

Despite suggestions that hands and brains coevolved, evidence remains circumstantial.

Here, we reveal a significant relationship between relatively longer thumbs – a key feature of precision grasping – and larger brains across 95 fossil and extant primates using Bayesian phylogenetic methods.

Most hominins, including Homo sapiens, have uniquely long thumbs, yet they and other tool-using primates conform to the broader primate relationship with brain size.

Within the brain, we surprisingly find no link with cerebellum size, but a strong relationship with neocortex size, perhaps reflecting the role of motor and parietal cortices in sensorimotor skills associated with fine manipulation.

Our results emphasise the role of manipulative abilities in brain evolution and reveal how neural and bodily adaptations are interconnected in primate evolution.

Source link