You might expect that with age comes a natural progression of brain degeneration, but new research shows that this might not be the case for all regions of the brain.

A new analysis of mouse and human brains suggests that some parts of the somatosensory cortex – the part of the brain that processes sensory information – aren’t just exempt from the thinning found in other parts, they actually grow stronger.

This result suggests that the brain’s ability to adapt and change continues, even into older age – and that the more you use it, the stronger your brain could be.

Related: Study Finds Humans Age Faster at 2 Sharp Peaks – Here’s When

“Until now, it had not been considered that the primary somatosensory cortex consists of a stack of several extremely thin layers of tissue, each with its own architecture and function. We have now found that these layers age differently,” explains neuroscientist Esther Kühn of the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases and the Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research in Germany.

“Although the cerebral cortex becomes thinner overall, some of its layers remain stable or, surprisingly, are even thicker with age. Presumably because they are particularly solicited and thus retain their functionality. We therefore see evidence for neuroplasticity, that is, adaptability, even in senior people.”

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to adapt to changing circumstances and requirements, reorganizing and rewiring its neural connections to support evolving needs. The assumption is that neuroplasticity peaks when you’re young, and gradually declines with age; however, this assumption is not necessarily supported by robust evidence.

Led by neuroscientists Peng Liu and Juliane Doehler of Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg in Germany, a team of researchers undertook a study of possible age-related changes in the human cerebral cortex, a folded region of the brain that usually thins with age.

“It is generally assumed that less brain volume means reduced function,” Kühn says. “However, little is known about how exactly the cortex actually ages. This is remarkable, given that many of our daily activities depend on a functioning cortex. That’s why we examined the situation with high-resolution brain scans.”

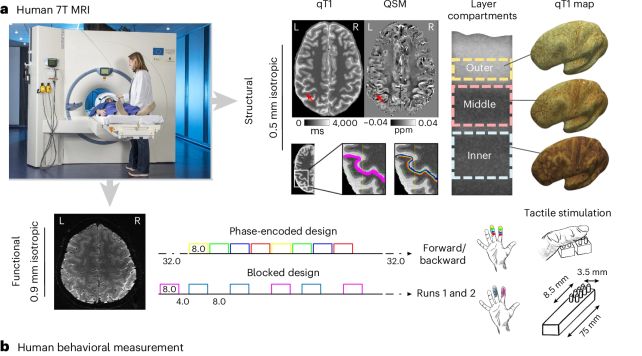

The researchers took particularly sensitive MRI brain scans of 61 adults between the ages of 21 and 80, focusing on a small region at the top of the brain called the primary somatosensory cortex, which receives tactile sensory information.

The researchers found that this region is structured a little bit like a stack of crepes: multiple layers of extremely thin, delicate tissue, each with its own role. These layers, the brain scans revealed, present differently depending on a person’s age.

Some are thinner in older people, as expected; but the middle and upper layers were found to be thicker in older people than the same layers seen in younger people.

“The middle layer is effectively the gateway for haptic [touch] stimuli. In the layers above, further processing occurs,” says Kühn. “For example, in the case of sensory stimuli from the hand, the upper layers are particularly involved in the interaction between neighboring fingers. This is important when grasping objects.”

The lower layers, by contrast, were thinner in the older patients. These are the layers that handle modulation, where tactile signals are amplified or suppressed, depending on context. For example, you don’t tend to feel your clothing unless you’re thinking about it – similar to the way your brain edits out your nose from your field of vision.

As to why different layers thicken or thin with age, the team suggests it could come down to the old adage of “use it or lose it.”

“The middle and upper layers of the cortex are most directly exposed to external stimuli. They are permanently active because we have constant contact with our environment,” Kühn says. “The neural circuits in the lower layers are stimulated to a lesser extent, especially in later life. I therefore see our findings as an indication that the brain preserves what is used intensively. That’s a feature of neuroplasticity.”

Interestingly, although the lower layers shrink, they may compensate for any cellular degeneration. Their myelin content was found to increase in response to an increase in a certain type of neuron that amplifies the modulation signal.

This is another sign of adaptability, and the researchers hope that, in future research, they may be able to find a way to promote these adaptive mechanisms.

“Together, our findings are consistent with the general idea that we can do something good for our brains with appropriate stimulation. I think it’s an optimistic notion that we can influence our aging process to a certain degree,” Kühn says.

The research has been published in Nature Neuroscience.

Source link