A badly crushed cranium unearthed decades ago from a riverbank in central China that once defied classification is now shaking up the human family tree, according to a new analysis.

Scientists digitally reconstructed the squashed skull, thought to be 1 million years old, and its features suggest that the fossil belonged to the same lineage as a striking specimen called “Dragon Man” and the Denisovans — an enigmatic and recently discovered population of prehistoric humans with murky origins. The skull’s age and categorization as an early Denisovan ancestor would mean the group originated much earlier than thought.

The researchers’ wider analysis, based on the reconstruction and more than 100 other skull fossils, has also sketched a radically different picture of human evolution, they reported Thursday in the journal Science.

The results significantly shift the timeline for species such as our own, Homo sapiens, and Homo neanderthalensis. Neanderthals, archaic humans who lived in Europe and Central Asia before disappearing around 40,000 years ago, are known to have lived alongside the Denisovans and interbred with them.

“This changes a lot of thinking because it suggests that by one million years ago, our ancestors had already split into distinct groups, pointing to a much earlier and more complex human evolutionary split than previously believed,” said study coauthor Chris Stringer, paleoanthropologist and research leader in human evolution at London’s Natural History Museum, in an email.

The findings, if widely accepted, would push back the emergence of our own species by 400,000 years and dramatically reshape what’s known about human origins.

The skull is one of two partially mineralized specimens unearthed in 1989 and 1990 in an area known as Yunxian in Shiyan, located in Hubei province in central China. A third skull discovered nearby in 2022 hasn’t yet been formally described in the scientific literature, Stringer noted.

“We decided to study this fossil again because it has reliable geological dating and is one of the few million-year-old human fossils,” said the study’s first author Xiaobo Feng, a professor at Shanxi University in China, in a statement. “A fossil of this age is critical for rebuilding our family tree.”

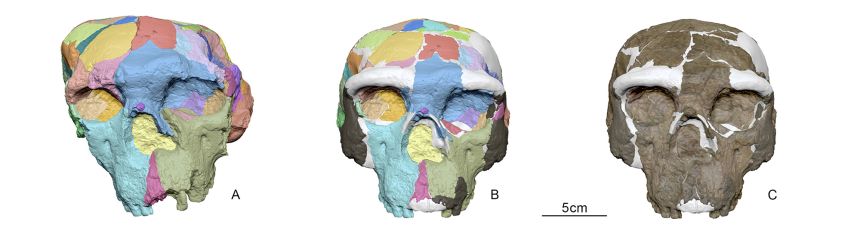

Both of the Yunxian skulls were deformed from millennia spent underground, but the second, known as Yunxian 2, was better preserved. That specimen formed the basis of the new reconstruction, which used cutting-edge CT scanning, light imaging and virtual techniques to separate the bones from the rock matrix that encased them, and to correct the distortions inherent in the fossil.

The skull’s age, determined by dating the layer of sediment in which it was found and mammal fossils found in the same layer, had led some experts to believe that it belonged to Homo erectus, a more primitive human species known to have lived in many places around the world at that point in time. However, while Yunxian 2’s large, squat braincase did resemble that of Homo erectus, other features of the skull, such as flat and shallow cheekbones, did not.

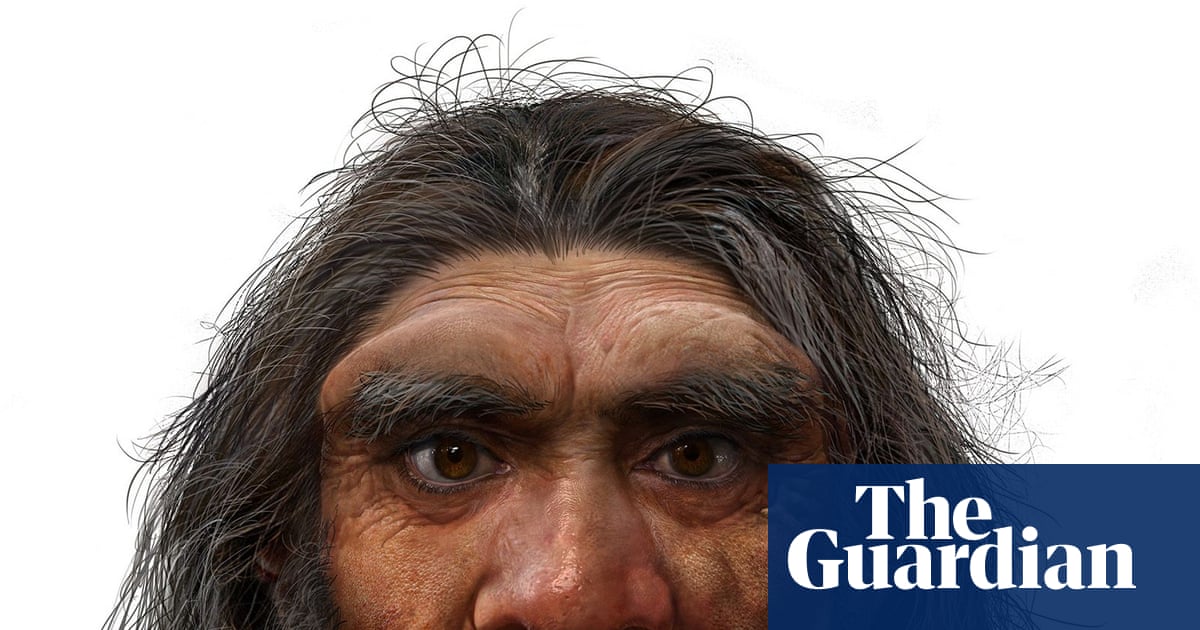

Stringer and his colleagues concluded that Yunxian 2 belonged to an early ancestor of Dragon Man, formally called Homo longi. Scientists identified Dragon Man in 2021 from a skull found at the bottom of a well in northeastern China, and authors of a June study used ancient DNA to link Homo longi to the Denisovans, a shadowy population known from genetic information extracted from a few fossil fragments but thought to have lived across much of Asia.

The latest analysis also suggests other hard-to-classify fossils uncovered in China should be grouped with Homo longi and the Denisovans — including fossils that another research team recently proposed as a newfound species they called Homo juluensis, a name that roughly translates to huge-headed man.

Stringer said the third Yunxian skull fossil, once researchers prepare and study it in detail, will enable the team to test the accuracy of the reconstruction and its placement within the human family tree.

With telltale bumps and ridges, skulls are particularly informative in the study of human evolution because they have a lot of characteristic features, and a skull is typically the specimen that can definitively confirm a newly discovered species.

Using information from the new digital reconstruction and anatomical information from 104 skulls and jawbones in the human fossil record, Stringer and his coauthor Xijun Ni, professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, reconstructed the evolutionary relationships between different groups using a mathematical program used in evolutionary biology. The team pieced together what’s known as a phylogenetic tree showing how different human species may have diverged from one another over the past 1 million years.

The analysis suggests that the origins of Homo sapiens, Denisovans and Neanderthals are much older than previously thought.

The finding challenges the traditional view, based on studies of ancient DNA, that the three species began to diverge from a common ancestor around 700,000 to 500,000 years ago — although it has never been clear who this ancestral species, sometimes dubbed Ancestor X, was.

The Denisovans and modern humans last shared a common ancestor about 1.32 million years ago, according to the new analysis. The Neanderthals branched away from that evolutionary line earlier, around 1.38 million years ago, the study suggested. The findings mean that Denisovans are more closely related to us than the Neanderthals, which had been viewed by many as Homo sapiens’ closest sister species, the researchers wrote.

The reconstruction of the warped skull looked good, said Ryan McRae, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC. McRae, who was not involved in the research, agreed it fit with Homo longi and the Denisovans.

However, McRae is less convinced by the phylogenetic tree analysis and said the team may have tried “to do too much at once with limited data.”

“This study says that Denisovans (Homo longi) and Homo sapiens are more closely related to the exclusion of Neanderthals,” he explained. “It also goes one step further saying that the origins of all these groups is much older than expected, about twice as old if not more. This would place the origins of all these groups firmly in the time of Homo erectus.

“At this point in time, I think the safer thing to say is that the Homo longi/Denisovan group and Homo sapiens (including very archaic fossils and modern humans both) look more similar to each other than they do to Neanderthals,” he added via email.

If the timing pointed out in this paper is accurate, McRae said the only candidate for the common ancestor of the Homo sapiens, Homo longi and Homo neanderthalensis would be Homo erectus. “There really isn’t another known species from the ~1.5 million year old time period that would make sense,” McRae said.

The human species Homo antecessor is known to have lived around 1 million years ago, and another, Homo heidelbergensis about 700,000 years ago, he added.

Stringer said he anticipated the findings would attract some skepticism, and the researchers plan to extend their analyses to include further sources of data and other fossils, including more from Africa, to refine the picture.

The study raises a broader question about where the ancestral populations of Homo sapiens, Neanderthals and Homo longi lived: inside or outside Africa, which is widely regarded as the cradle of humankind, Stringer noted.

The authors said that while the study makes some progress toward resolving what paleoanthropologists call the “muddle in the middle” — the confusing array of human specimens in the fossil record between 1 million and 300,000 years ago — finds like the Yunxian 2 skull also underscore just how much scientists have to learn about human origins.

“When I began working in human evolution over fifty years ago the East Asian record was either marginalised, or its fossils were only ever considered as direct ancestors of recent East Asians,” Stringer said by email. “But what we now see from Yunxian — and from … many other sites — is that East Asia preserves crucial clues to the later stages of human evolution.”

Source link