A new study published in L’Anthropologie is shedding light on a remarkable discovery from Skhul Cave in Israel. Researchers have reanalyzed the remains of a 140,000-year-old child, and the findings suggest that the child could have been a hybrid between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. This revelation challenges long-held assumptions about early human evolution and may provide new insights into the complex relationships between our species and our closest extinct relatives.

A Mysterious Discovery

The child’s remains were first uncovered in 1931 in Skhul Cave, a site that holds significant historical importance as one of the earliest known locations for organized human burials. Over the years, the fossils found here were generally thought to belong to Homo sapiens, with some even speculating that the site represented a transitional stage between modern humans and Neanderthals. Yet, the exact classification of these remains has always been a matter of debate.

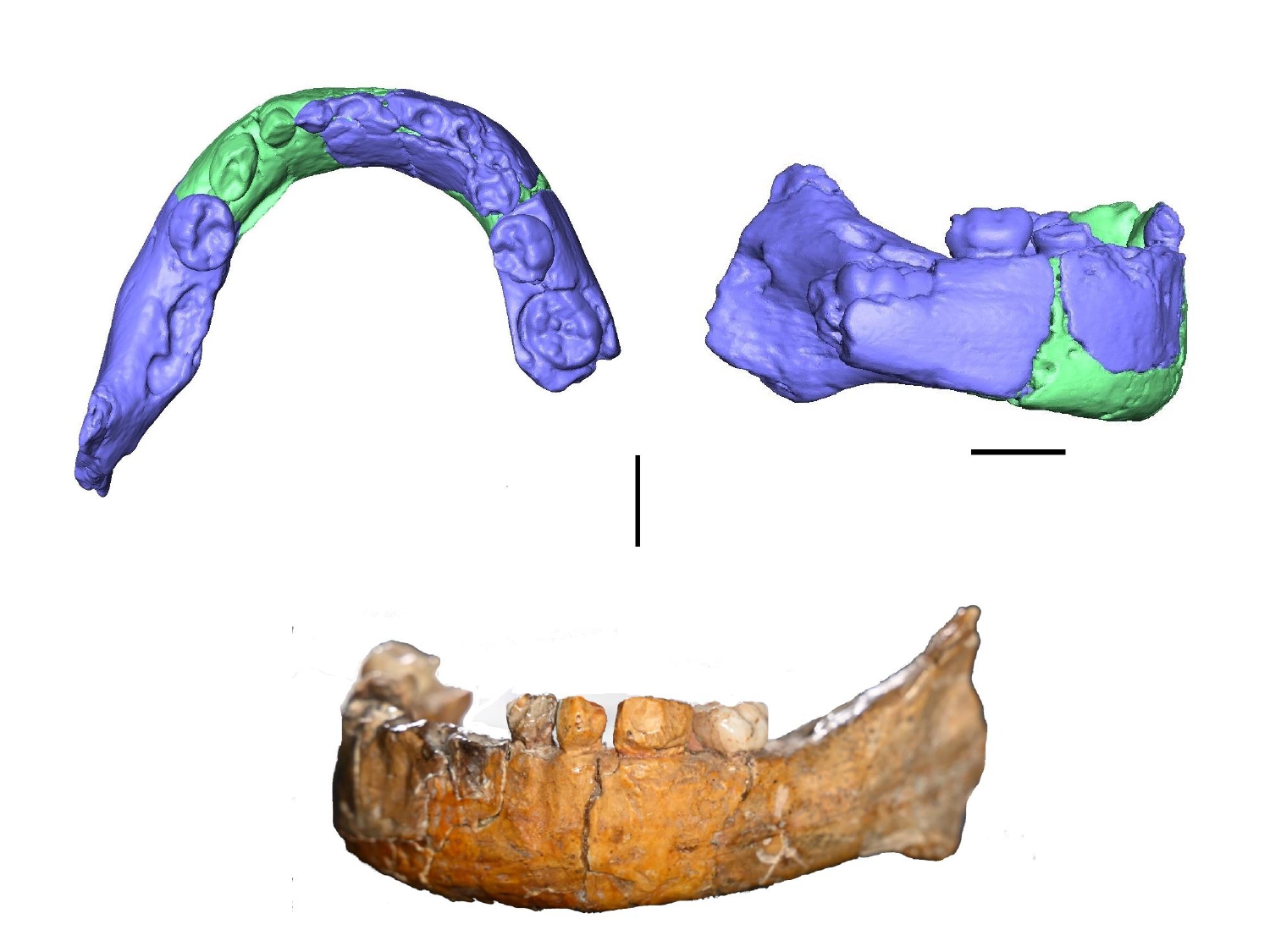

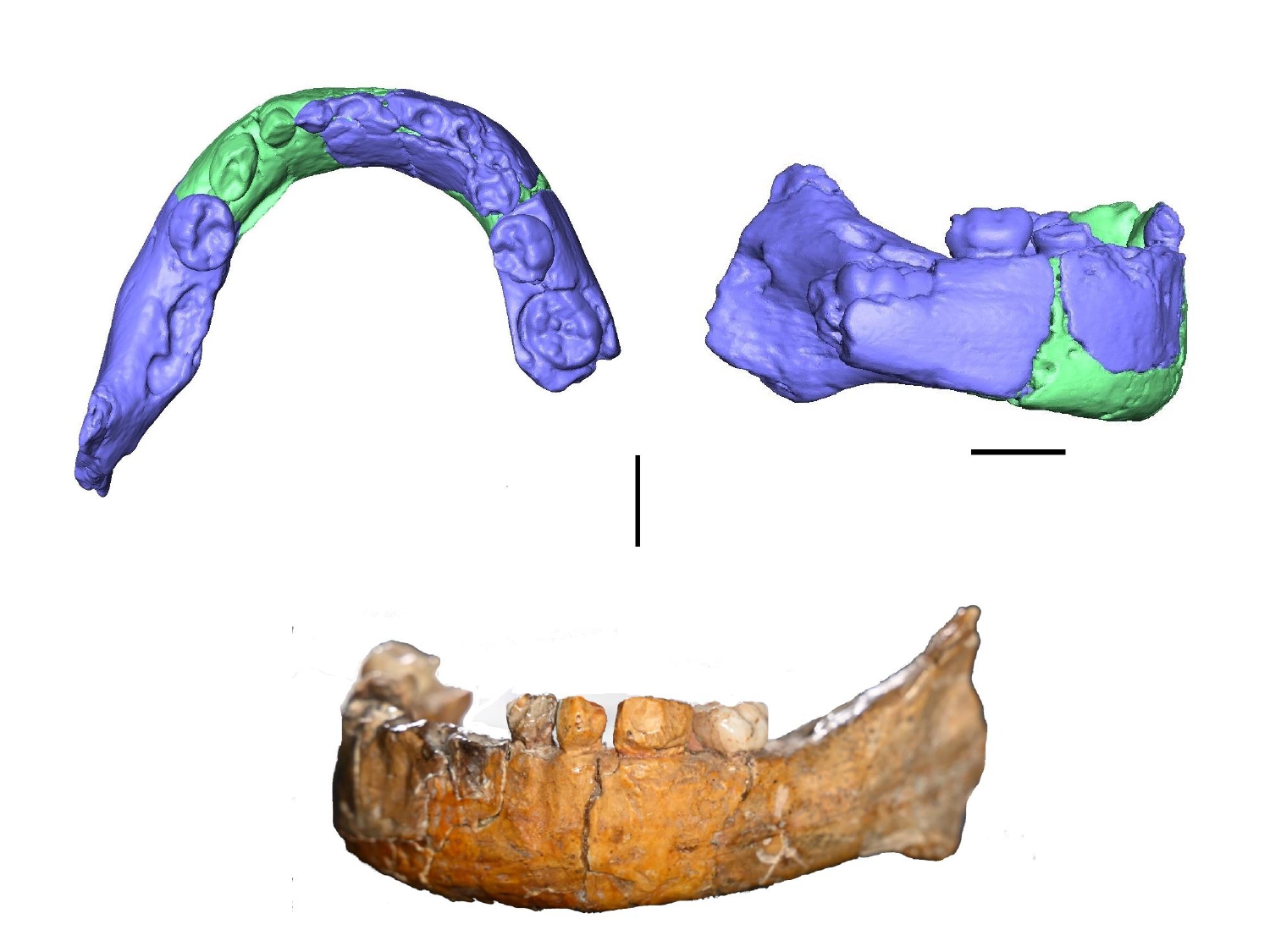

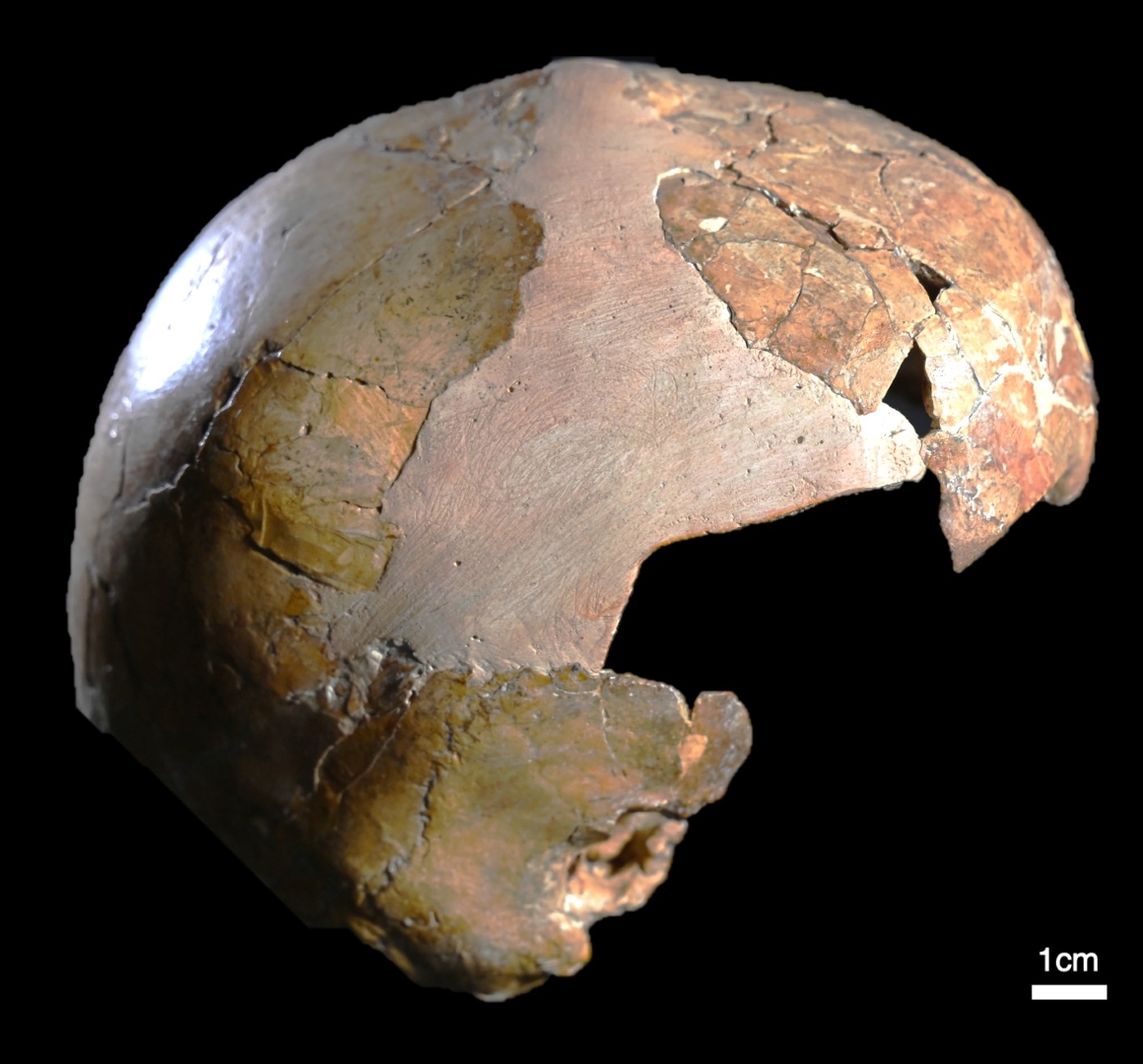

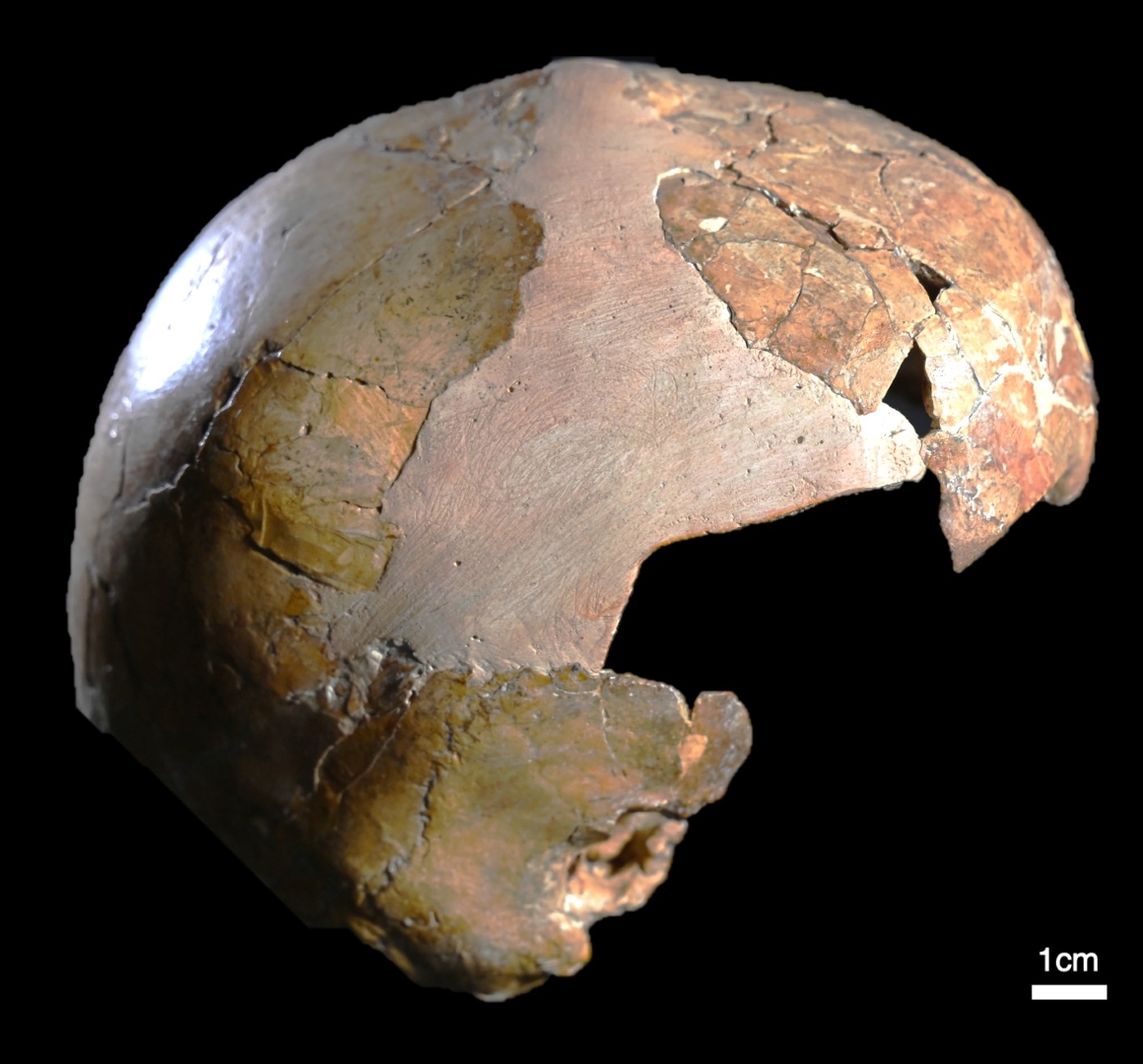

The child in question, named Skhul I, was likely between 3 and 5 years old at the time of death. The skull, although fragmented and partially reconstructed with plaster, still offers valuable clues about the child’s ancestry. The latest study, led by paleoanthropologist Anne Dambricourt Malassé and her team, used advanced CT scanning techniques to create detailed 3D models of the skull, revealing a mix of features that seem to combine both modern human and Neanderthal traits.

Hybrid Features Revealed by CT Scans

The most striking aspect of the research is the combination of features found in the child’s skull. According to the study, the neurocranium—part of the skull that houses the brain—displays characteristics typically associated with Homo sapiens, including a more vertical orientation of certain bones. However, the jaw shows a clear resemblance to Neanderthal features, such as the absence of a chin and a wide, rounded dental arch.

This mixture of anatomical traits is what led the researchers to propose that Skhul I might have been a hybrid—a child with one Homo sapiens parent and one Neanderthal parent. “The morphology of the skull, especially the mandible, suggests the child was objectively a hybrid,” said Malassé. She explained that these features were distinctive enough to separate the individual from pure Homo sapiens, but still clearly distinct from typical Neanderthal characteristics.

Skepticism from Some Experts

While the hybrid theory is intriguing, not all experts are convinced. Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, expressed caution, noting that the fossils from Skhul Cave, in general, align more closely with Homo sapiens. Stringer acknowledged that there could have been some genetic mixing between species, but he believes that the evidence from Skhul Cave does not necessarily confirm a first-generation hybrid.

Similarly, John Hawks, a prominent anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin, pointed out that human populations can exhibit significant physical variation, even without interbreeding with other species. Hawks emphasized that without genetic data, it is difficult to definitively classify the child as a hybrid based solely on physical traits. As he put it, “Human populations are variable, and there can be a lot of variability in their appearance and physical form even without mixing with ancient groups like Neanderthals.”

The Role of Skhul Cave in Human Evolution

Beyond the hybrid hypothesis, the study of Skhul I provides important insights into the broader context of early human behavior. Skhul Cave is considered one of the first organized burial sites, offering a glimpse into the rituals of ancient humans. While the origins of burial practices are still debated, this new analysis suggests that both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals may have shared similar practices in this regard.

The debate over the hybrid nature of Skhul I also raises broader questions about the interactions between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. Genetic evidence has shown that modern humans carry traces of Neanderthal DNA, indicating that interbreeding did occur. This new study, however, challenges us to rethink the nature of these interactions—were they occasional encounters, or did Neanderthals and Homo sapiens coexist and interbreed more regularly than previously believed?

Source link