Mount Tabor must have a better publicist, because Rocky Butte is really Portland’s more important and influential extinct volcano. The Rocky Butte Preservation Society is doing its best to promote its mountain’s reputation with a slew of informative newsletters, history walks and trash cleanups. The society will host what its organizers say is the the first concert inside Rocky Butte’s historic tunnel on Saturday, Sept. 20, featuring a dozen artists. (The tunnel will be closed to traffic.)

Local musicians, including Michelle and the Beards, Kate Power and Steve Einhorn, The Glyptodons, Morning Breath, Nathaniel Holder, and Alex the Saxophonist (the latter of whom has gained local attention for his regular nighttime solo jams in the tunnel), will deliver a free concert to celebrate the 86th anniversary of the tunnel’s opening. The bill will present a mix of folk, jazz, bluegrass, and a bit of Celtic music. There will be audience sing-alongs, and guests are encouraged to bring seating and potluck food.

“It’s such an acoustic opportunity with this key arched barrel that’s super huge,” says Graham Houser, who runs the society and organized the show. “A neighbor and I were talking about the choral classes that he leads. We work together to lead a hike up to the tunnel, and on one we all learned songs. About 20 of us were singing them all together, and it was so cool to just be singing with people in the space.”

The Rocky Butte Preservation Society was formed in 1985 by David Lewis, who grew up in the area in the ’50s. At the height of the society’s activity, the nonprofit organization got Rocky Butte Scenic Drive—the road from Northeast Fremont Street to Joseph Wood Hill Park on top—added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1991. In 1995, its members got lamps installed, modeled after those at Vista House in the Columbia River Gorge. They built trails in the area and planted native foliage.

But the society’s active membership had dwindled significantly by the time Houser moved to Madison South in 2013. As a resident, he began to independently glean the importance of Rocky Butte and its quirky history. He wrote newsletters distributed door to door and in little free libraries. He even designed a sharp-looking flag for Rocky Butte that incorporates the Cascadia colors and the distinctive lamp icon.

“I started researching hyperlocal neighborhood history in The Oregonian archives,” Houser says. “I kept finding all these super-cool things in my backyard, started compiling it. Talking to other neighbors, I found the preservation society and have been working with them ever since.”

The society’s early work, enhanced by Houser’s independent research, reveals the history worth preserving at Rocky Butte. The Missoula Flood formed the volcano’s modern features and laid the literal groundwork for Portland as we know it between 15,000 and 18,500 years ago, hundreds of centuries after Rocky Butte’s last eruption. A sixth “great lake” in today’s Montana, with more volume than Lakes Erie and Ontario combined, was held back by an ice dam. Until one warm day in the Holocene Epoch, it suddenly was not.

The 1,000-foot wall of water traveled through three states. It shaved off Rocky Butte’s river-facing side, creating a sheer cliff and deposited everything from car-sized boulders to endless gravel. Pretty much everything in downtown Portland made of stone, and most vintage lumber homes’ non-brick fireplaces, came from Rocky Butte. The volcano even formed its own unique gemstone. Rocky Butte jasper has abstract swirls of green, blue, turquoise, brown and orange that evoke the local landscape (take that, Tabor!).

Chinookan-speaking natives called the butte Mowitch Illihee, meaning home of the deer. They chased those deer over the cliff or into concealed pits lined with spikes on the slope (some of which still exist on the east side). Cedar longhouses surrounded the area before Caucasians arrived.

A gun range where Northeast Hancock Drive dead-ends at 95th Avenue was active from the 1890s to the 1960s. “Turkey shoots” were common, especially at Thanksgiving. They didn’t hunt wild turkeys, or even a corral filled with birds, but something more devious. A turkey was tied behind a log or fence, with enough slack to run left and right. He was mostly concealed, unless he popped up his head, at which point contestants with small bore rifles or pistols fired. (The Academy Award-winning 1941 film Sergeant York has a similar turkey shoot scene.)

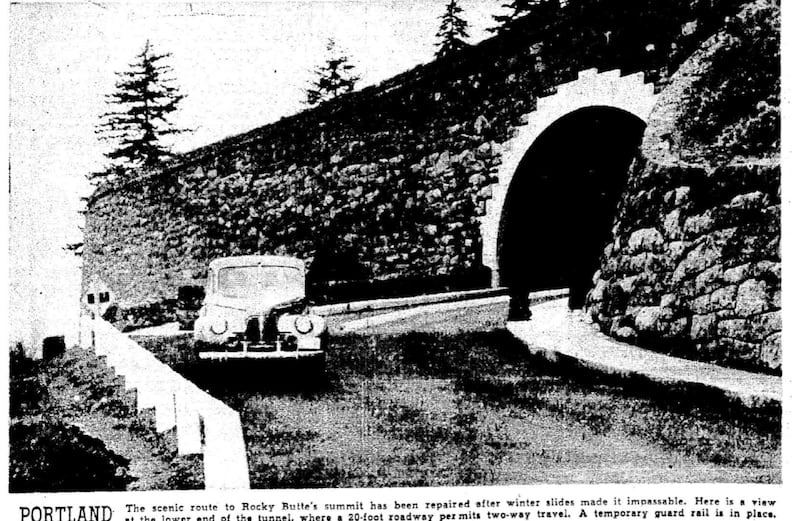

The Works Progress Administration opened the Rocky Butte tunnel in 1939 with a grand celebration, after an estimated 700 men spent five years building it by hand. The tunnel together with the fortress-like structure on top was Oregon’s second-most expensive WPA project, after Timberline Lodge. Key statistics: The tunnel is 27 feet tall, 34 feet wide, and 375 feet long and curves 257 degrees over itself. From 82nd Avenue in winter, when the trees are bare, both openings of the tunnel are visible.

Houser’s detective work also revealed that Rocky Butte has been the scene for some of modern Portland’s weirder aspects. For example, “flaming jalopy jumps” were a recurring spectacle in the 1930s. Old cars were set ablaze and pushed over the edge toward Fremont Street, sponsored by the Automotive Dealers Association as a promotion for steel recycling and attended by hundreds of Portlanders. (An Italian newsreel crew filmed one in 1938.)

“I think Portlanders should know that Rocky Butte is a historically unique, culturally relevant, ecologically active and geologically rich landmark of the urban-natural divide in Portland,” Houser says. “I keep working on this project because I want to safely hike around the butte with my kids and friends.”

SEE IT: Rocky Butte Tunnel 86th Anniversary Concert at Rocky Butte Scenic Drive (park near Northeast 92nd Avenue and Russell Street), rockybuttepreservationsociety.org. 4 pm Saturday, Sept. 20. Free.