There’s a parasite living in the brains of 40 million Americans, and most of these human hosts are completely unaware.

Doctors don’t usually treat this bug unless it begins wreaking havoc on the bodies of patients with weakened immune systems, but a new discovery may make short work of the invader without the typical risks.

Parasitologist Rajshekhar Gaji runs a lab at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, investigating what makes the parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, tick.

Related: Cat Parasite Can Seriously Disrupt Brain Function, Study Suggests

“The parasite that’s sitting in the brain gets reactivated, starts multiplying, and then it’s fatal,” Gaji explains. “Because of that, the parasite is a dreaded pathogen.”

T. gondii is closely associated with cats, which are the only known hosts within which the parasite can reproduce sexually. But once its offspring are shed in the cat’s poop, there are very few warm-blooded species T. gondii won’t make a home in.

For most of us, an infection with T. gondii will fall completely under the radar. For those with cancer, HIV, or who are on immunosuppressants, the parasite presents significant risks.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>Without a healthy immune system to keep T. gondii at bay, these patients can quickly develop a disease known as toxoplasmosis, which can bring flu-like symptoms, swollen lymph nodes, and brain inflammation.

The parasite can also be transmitted to the placenta of a developing fetus during pregnancy. This form of the disease, congenital toxoplasmosis, can cause developmental problems, and even miscarriages.

Treatments for acute toxoplasmosis involve medications that target mechanisms in the parasite that are biologically similar to processes in our own bodies. This often puts patients at risk of severe side effects, restricting treatments to situations where infections are considered to be dire.

Gaji and his team might have found a lead, though: in a new study, they have shown that switching off just a single protein inside the microscopic parasite can kill it.

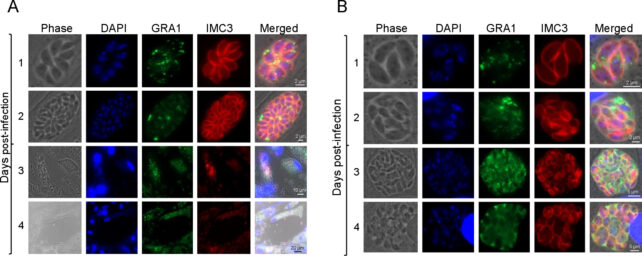

The protein, TgAP2X-7, appears to be essential to the parasite’s ability to invade a host, form plaques, and self-replicate. To prove this, the team genetically modified some parasites so that their TgAP2X-7 proteins function normally unless auxin (a plant hormone that regulates growth) is added, in which case the proteins would quickly degrade.

Auxin, they established prior, had no impact on T. gondii growth or plaque formation on its own, so any effect it had on the genetically modified parasites could be attributed to the fact that the TgAP2X-7 proteins had been destroyed.

Deprived of TgAP2X-7, the parasites couldn’t form plaques, and their ability to invade hosts (which, in this lab study, were human foreskin cells) was severely impaired.

Usually, they have a near-100 percent success rate invading these kinds of cells, but without that key protein, success dropped to below 50 percent. They also struggled to replicate.

“These parasites completely stop growing, and they cannot survive,” Gaji says. “That shows this particular transcription factor is essential for the parasite to survive within the host.”

Best of all, this protein bears no similarities to anything in the human body, which means there’s potential to target it without harming patients.

“There is a critical need for the identification and development of novel therapeutic options to treat Toxoplasma infections,” first author parasitologist Padmaja Mandadi and team write.

“Unique transcription factors that regulate the expression of proteins involved in these lytic cycle events could open new opportunities for therapeutic interventions.”

Given that much of the damage wrought by T. gondii comes from repeated cycles of cell invasion, replication, and destruction, knowing how to interrupt these cycles could lead to new ways of treating the disease.

This research was published in mSphere.

Source link