Under dim Capitol Hill streetlights on September 20, Gary Dziekan headed down 8th Street Northeast dressed in lederhosen, walking home from the Oktoberfest party he co-hosted five blocks away. Dziekan, who goes by “Zeek,” crossed at the intersection with C Street, zeroing in on the short iron gate separating a colorful row of two-story homes from the quiet Washington, DC, street.

Just steps from the skinny green rowhouse where his wife and two young sons slept, footsteps quickened in the crosswalk behind Zeek, pounding the asphalt.

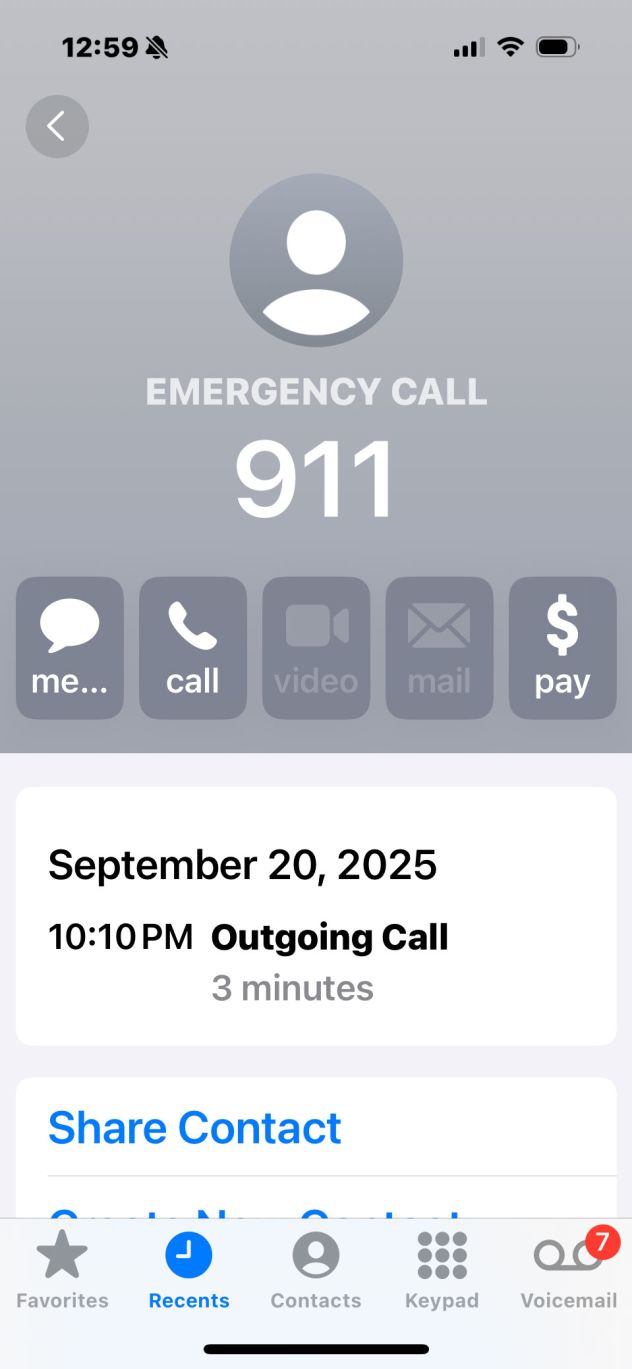

Zeek, an off-duty DC firefighter, turned to find a masked man aiming a gun at him. The man tried to rob him, causing a scuffle that ended with Zeek shot, lying on the ground, dialing 911. Zeek waited for three minutes — clutching his bleeding wound — with no answer from the emergency number before he called his own firehouse, begging for help.

His unanswered call marks the latest critical misstep by the capitol city’s embattled dispatch system, Zeek, who works with DC 911 daily as a first responder, said. DC’s Office of Unified Communications (OUC), which handles 911 operations in the city, has long been saddled with staffing shortages, hiring difficulties and botched dispatches manifesting dangerous conditions for some callers over the years.

The shooting also comes as reported crime across the capitol city has fallen since the Trump administration launched a sweeping takeover of policing, unleashing a flood of federal law enforcement on to DC’s streets in August.

While Zeek had seen National Guard troops and other agents patrolling around his neighborhood before, he was alone on Saturday night — without federal protection or assistance from 911 — forced to take matters into his own hands.

“Give me your cell phone,” the robber demanded when Zeek turned around.

“Here, take everything,” Zeek said, offering his phone and a bag carrying his wallet, sunglasses, and a Bluetooth speaker. The robber lifted the phone to Zeek’s face to unlock it, and, when the digital wallet failed to open, shoved the barrel of the gun against Zeek’s chest.

“He was gonna kill me,” Zeek told CNN. “100% going to shoot me in the chest, right there, just a few feet from my door.”

So, in an instant, Zeek twisted and pushed the barrel aside, but the robber grabbed his shoulder, firing a shot that cracked through the quiet. The bullet passed through the robber’s fingers and into Zeek’s chest and shoulder.

The shooter bolted, dropping the gun, the bag and the phone. Zeek crumpled onto the pavement, tugging loose the straps of his lederhosen so he could use his shirt to press on the bloody wound.

He grabbed his phone, dialed 911 on speaker, and set it beside him. It rang for three minutes without an answer as the firefighter lay bleeding in the street.

Zeek was still sprawled and bleeding when the robber’s hammering footsteps returned, breaking through the automated voice on the phone.

Sure that the man had returned to kill him, Zeek grabbed the gun lying near the curb where it was dropped. He loaded fresh rounds and fired at the shooter who was running at him, forcing him to flee for good.

When a neighbor came outside to help, offering to call 911, Zeek instructed him to call a different number instead — the direct line to the fire station he worked at, Engine 18 Truck 7, just six blocks away. Zeek’s voice cracked through the neighbor’s phone when the station answered: “It’s Zeek. I’ve been shot and I need help. I’m at 8th and C Northeast.”

Within minutes, emergency lights from his firetruck and from Metropolitan Police cars were dancing off the windows of 8th Street’s quiet row of houses. Medics — some of them his friends — tore away Zeek’s blood-soaked costume, bandaged his arm and chest, and rushed him to the hospital.

Two days later, Zeek was home with his family again, fragments of the bullet still lodged in his shoulder between a block of nerves and main blood vessel. Doctors said it’s too risky to remove the bullet and consider him lucky that it didn’t do more damage.

Looking back, Zeek said he never spoke to anyone at 911 on the night of the shooting.

“I’ve always had this idea in the back of my head, if something went wrong that I know if I called the firehouse, I would get service faster (than 911),” Zeek said. “But I didn’t think I’d ever actually be in this position.”

OUC received over 20 calls to 911 within 10 minutes of the incident on 8th Street the night of the shooting, a spike in typical call volume, and dispatchers processed them “as quickly as possible,” OUC Director Heather McGaffin said in a statement.

In DC, 911 calls are answered in the order that they are dialed. OUC says the first call for the shooting that dispatchers answered was picked up just after 10:11 p.m., but it’s not clear how long that caller was on hold before OUC answered. The call log on Zeek’s phone shows he dialed the three-digit number at 10:10 p.m., disconnecting after no one picked up for three long minutes.

“We recognize that during incidents which create an increase in call volume, some callers are placed in queue while call takers gather pertinent information and provide lifesaving direction to other callers,” McGaffin’s statement said.

911 call spikes are as sporadic as the emergencies prompting them, making it impossible for call centers in any city to plan for them and staff accordingly.

But OUC was already understaffed on the night of September 20, an OUC spokesperson told CNN. Night shifts have a minimum staffing target of 17 call takers, but only 16 people — six of whom were working overtime — were on staff that night.

All 16 workers were taking calls after 10 p.m. when Zeek was shot, the OUC spokesperson said.

Fire and EMS were dispatched to Zeek’s location after 10:12 p.m., and MPD was dispatched after 10:13 p.m., according to dispatch logs shared by OUC. The crew from Zeek’s fire station were the first to arrive at 10:17 p.m., with other responders close behind.

Generally, OUC has struggled to manage call volumes as the agency faces significant, years-long staffing challenges, reporting less than 57% of its shifts met staffing targets during the month of August. Last year, the agency went as far as to offer monthly bonuses to employees who show up to all their scheduled shifts, CNN affiliate WUSA9 previously reported.

Zeek said “it’s not shocking” his 911 call went unanswered.

“I see it at work every day – every day there’s problems,” he said. “Then I’m off duty, I need OUC, and I don’t even get an answer. That’s really despicable.”

Working as a firefighter in the city, Zeek called the clarity of dispatches from OUC personnel “absolutely horrendous,” leaving his crew scrambling for direction. Dispatchers relay incorrect addresses to them almost daily, he said, massively delaying their response to people experiencing emergencies.

“If an address gets put in the computer wrong and sends you in the wrong direction, that’s somebody’s life in the balance,” he said. “It causes a serious problem for the safety of the citizens, and OUC just refuses to own up to their own mistakes.”

The agency “works closely” with city public safety partners “to help ensure that each response is timely and well-coordinated,” McGaffin’s statement said.

On the other side of public safety in DC, police officers and federal agents – working in tandem as the result of President Donald Trump’s crackdown on crime in the capital city — located and arrested the high schooler who allegedly robbed and shot Zeek that night.

“FBI agents, along with federal partners and MPD, aggressively apprehended the subject, took him into custody, and also participated in a number of interviews,” Darren Cox, assistant director in charge of FBI Washington Field office, said during a Monday news conference.

Court documents identified 17-year-old Marcellus Dyson, Jr. as the suspect. CNN has reached out to his attorney for comment.

After running from the shots Zeek fired at him, Dyson allegedly approached a witness one street over, telling her he had been shot and needed help, according to the affidavit. The witness was walking Dyson to a nearby hospital before responding officers stopped them and detained the teen.

The high schooler was initially arrested for assault with the intent to rob, but he now faces the power of the District’s top prosecutor, former Fox News host Jeanine Pirro, who has carried out the president’s demand for intense prosecutions with gusto.

Her office pushes for harsher charges or time in jail for even low-level offenders. Cases are flooding the courts, with hearings in DC’s local criminal court routinely lasting late into the night and federal prosecutors awakened for new cases.

Pirro announced Monday Dyson would be tried as an adult, under Title 16, as he faces upgraded charges of armed robbery, possession of a firearm during a crime of violence and aggravated assault while armed.

At a Friday preliminary hearing, the court rejected the defense’s request to release Dyson. His next court appearance is scheduled for October 7.

Pirro called Zeek the same day she announced the new charges for the suspect, the firefighter said.

“I am 100% behind her,” he said. “Somebody needs to be the example.”

Zeek, who is raising his 13- and 10-year-old sons in the rowhouse on 8th Street, said there should be consequences for young people in the city committing violence to deter others.

“If it stops the next person from getting robbed, shot, assaulted, anything – great. And I think it will,” he said.

While he believes the deployment of federal enforcement agents have helped make DC safer, he can’t shake the unease that a 17-year-old with a gun left him with just steps from his own front door.

“Up until Saturday, I was more than happy to live where I was living,” he said. “But it has made me wonder what my future with my family living in the city looks like.”

Source link