A newly-declared species of 247 million-year-old Triassic reptile and its ridiculously large crest has left scientists scratching their heads.

The crest is unlike anything seen before, and was neither made out of skin, as in the case of pterosaur crests, nor feathers, as in the case of raptors and eventually birds.

It wasn’t a kind of hair either, and in fact, the animal is now being used as a study case for the origin of protrusions of all kinds.

At the most fundamental level, feathers and hair are complex appendages that have important functions such as forming insulation, aiding sensation, providing displays, and contributing to flight.

Both feathers and hair have their origins in stem lineages of birds and mammals, respectively. However, the genetic toolkit for the development of these appendages is likely to have deeper roots among amniotes—the branch of animals that encompasses reptiles, birds and mammals.

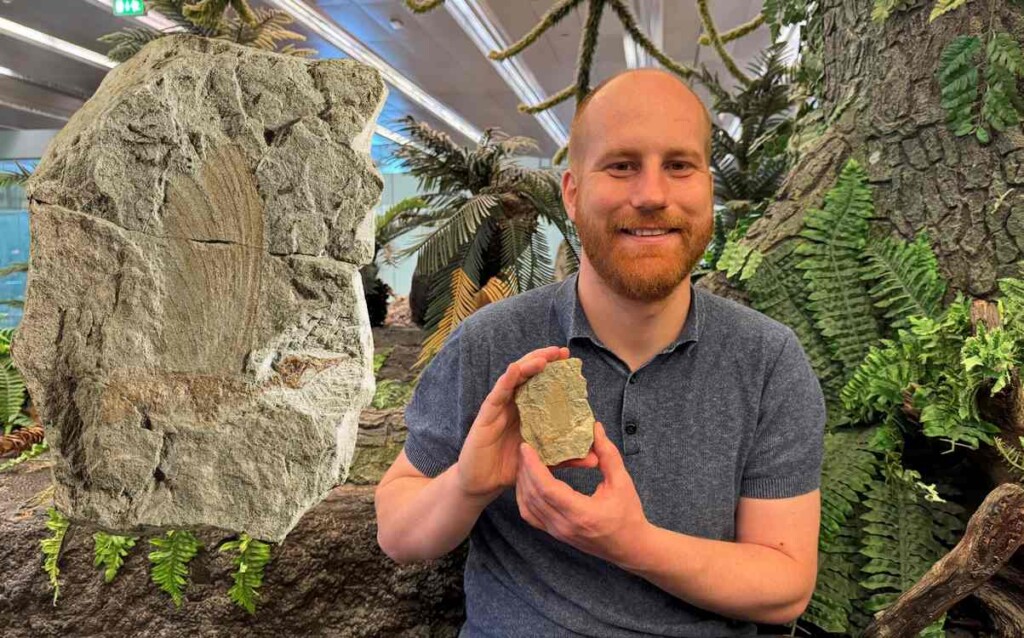

In a paper published yesterday in Nature, Stephan Spiekman and colleagues describe a small animal with a distinctive crest of appendages up to 6 inches tall along its back. Although the reptile has a superficially bird-like skull, it was been assigned to a clade of Triassic reptiles called Drepanosauromorpha and named Mirasaura (meaning wonderous reptile).

The Triassic Period was the ‘good ‘ole days’ of reptilian domination and evolution on the planet, and many reptiles still alive today such as the lizard, crocodilian, and turtle first appeared during this age of the Earth which predated the dinosaurs.

Two well-preserved skeletons with plumes of Mirasaura, along with 80 specimens with isolated appendages and preserved soft tissues were examined after arriving in the State Museum of Natural History in Stuttgart, Germany.

All fossils are dated to be around 247 million years old and the first were found in northeastern France in the 1930s but remained unidentified until further preparation was undertaken in recent years. This allowed the crests and skeletal remains to be associated with each other.

“The material has been variously described over the years as including parts of a reptile skeleton, a fish fin, an insect wing or plant parts, or was called unidentifiable,” reports Dr. Richard Prum, a paleoecologist from Yale University in a commentary piece on the discovery.

It’s very rare to have soft tissues preserved from so long ago, and it allowed Spiekman et al. to get a closer look at exactly what the appendages were made of when the animal was alive.

MORE WONDROUS ANIMALS: Scientists Discover Oldest Bird Fossils, Rewrite History of Avian Evolution

They contain melanosomes (pigment-producing cells found in skin, hair, and feathers) that are more similar to those seen in feathers than in reptilian skin or mammalian hair, although they lack the typical branching patterns seen in feathers.

It suggests that such complex appendages already evolved among reptiles before the origin of birds and their closest relatives, which may offer new insights into the origin of feathers and hair.

MORE REPTILIAN HISTORY: Two Halves of the Same Fossil Stored at Different Museums Reunited to Form New Species

“[T]hese appendages must have been a striking and unusual feature of the animal’s appearance. They also must have been awkward to carry around, given that the longest is more than one-third of the length of the entire creature,” Dr. Prum adds.

Considering the function of the appendages seen in Mirasaura, Spiekman and colleagues rule out roles in flight or camouflage and instead suggest a possible role in visual signaling, perhaps for mating purposes, or even to deter predators like the spots on a butterfly’s wings.

SHARE This Wild New Reptile Shaking Up Biology On Social Media…