Neanderthals may have never truly gone extinct, according to new research – at least not in the genetic sense.

A new mathematical model has explored a fascinating scenario in which Neanderthals gradually disappeared not through “true extinction” but through genetic absorption into a more prolific species:

Us.

According to the analysis, the long and drawn-out ‘love affair’ between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals could have led to almost complete genetic absorption within 10,000–30,000 years.

Related: Mysterious Twist Revealed in Saga of Human-Neanderthal Hybrid Child

The model is simple and not regional, but it provides a “robust explanation for the observed Neanderthal demise,” argue computational chemist Andrea Amadei from the University of Rome Tor Vergata and his colleagues.

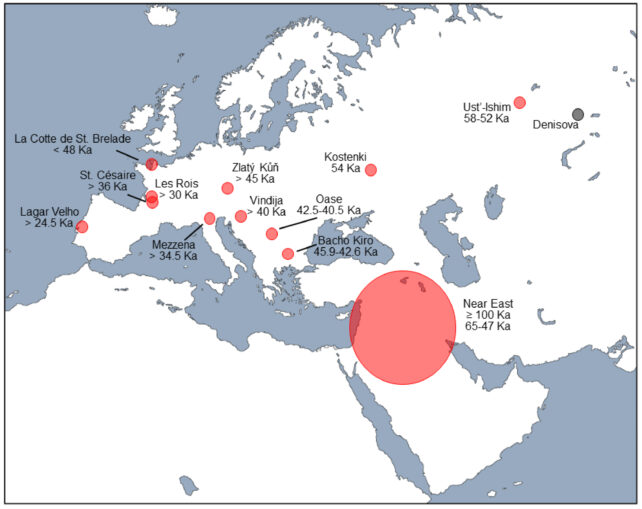

Once, the idea that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens interbred was a radical notion, and yet now, modern genome studies and archaeological evidence have provided strong evidence that our two lineages were hooking up and reproducing right across Eurasia for tens of thousands of years.

Today, people of non-African ancestry have inherited about 1 to 4 percent of their DNA from Neanderthals.

No one knows why Neanderthals disappeared from the face of our planet roughly 40,000 years ago, but experts tend to agree that there are probably numerous factors that played a role, like environmental changes, loss of genetic diversity, or competition with Homo sapiens.

Amadei and co-authors – evolutionary geneticist Giulia Lin from the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, and ecologist Simone Fattorini from the University of L’Aquila in Italy – present a model that does not rule out these other explanations.

It does suggest that genetic drift played a strong role – even with the researchers assuming the Neanderthal genes our species ‘absorbed’ had no survival benefit.

If the model were to include the potential advantages of some Neanderthal genes to the larger Homo sapiens population, then mathematical support for genetic dilution may become even stronger.

Like all models, this new one is based on imperfect assumptions. It uses the birth rates of modern hunter-gatherer tribes to predict how quickly small Neanderthal tribes would be engulfed by a much larger human population, given how frequently it seems we were interbreeding.

The results are consistent with recent archaeological discoveries and align with a body of evidence that suggests the decline of Neanderthals in Europe was gradual rather than sudden.

Homo sapiens seem to have started migrating out of Africa much earlier than scientists previously thought, and they arrived in Europe in several influxes, possibly starting more than 200,000 years ago.

As each wave of migration came crashing into the region, it engulfed local Neanderthal communities, diluting their genes, like sand pulled into the sea.

Today, some scientists argue that there is more to unite Homo sapiens and Neanderthals than there is to differentiate us. Our lineages, they say, should not be regarded as two separate species, but rather as distinct populations belonging to a “common human species.”.

Neanderthals were surprisingly adaptable and intelligent. They made intricate tools, created cave art, and used fire – and when it came to communication, they were probably capable of far more than simple grunting.

Neanderthal populations and cultures may no longer exist, but their genetic legacy lives on inside of us.

These are not just our cousins; they are also our ancestors.

The study was published in Scientific Reports.

Source link