One of the worlds in the TRAPPIST-1 system, a mere 40 light-years away, just might be clad in a life-supporting atmosphere.

In exciting new JWST observations, the Earth-sized exoplanet TRAPPIST-1e shows hints of a gaseous envelope similar to our own, one that could facilitate liquid water on the surface.

Although the detection is ambiguous and needs extensive follow-up to find out what the deal is, it’s the closest astronomers have come yet in their quest to find a second Earth.

Related: The Red Sky Paradox Will Make You Question Our Very Place in The Universe

“TRAPPIST-1e remains one of our most compelling habitable-zone planets, and these new results take us a step closer to knowing what kind of world it is,” says astronomer Sara Seager of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), co-author on one of two papers detailing the findings.

“The evidence pointing away from Venus- and Mars-like atmospheres sharpens our focus on the scenarios still in play.”

In the search for habitable worlds outside the Solar System, Earth is astronomers’ blueprint. That’s because, in all the Universe, Earth remains the only world on which we know for a fact that life has emerged and thrived.

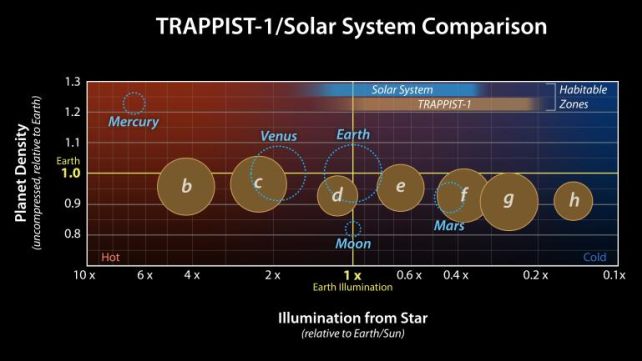

One major Earth-like characteristic that scientists look for is the ability to host liquid water – a material that is absolutely crucial for biochemical processes. This means the first step is finding exoplanets that are the right distance from their host star, occupying a zone where water neither freezes under extreme cold nor evaporates under extreme heat.

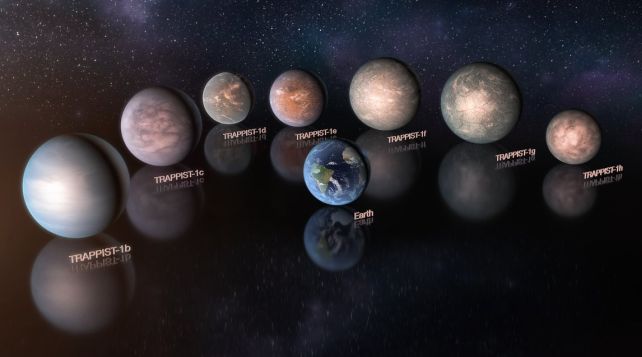

Announced in 2016, the discovery of the TRAPPIST-1 system was immediately exciting for this reason. The red dwarf star hosts seven exoplanets that have a rocky composition (as opposed to gas or ice giants), several of which are bang in the star’s habitable, liquid water zone.

But there are more criteria to satisfy. For liquid water to stay liquid and not sublimate as it does in a vacuum at habitable temperatures, it needs an atmosphere to keep it stable.

This is where it gets a little tricky for the TRAPPIST-1 system. Red dwarf stars are significantly cooler than stars like the Sun, making their habitable zone much closer. Red dwarf stars are also much more active than Sun-like stars, rampant with flare activity that, scientists have speculated, may have stripped any planetary atmospheres in the vicinity.

Closer inspections of TRAPPIST-1d, one of the other worlds in the star’s habitable zone, have turned up no trace of an atmosphere. But TRAPPIST-1e is a little more comfortably located, at a slightly greater distance from the star.

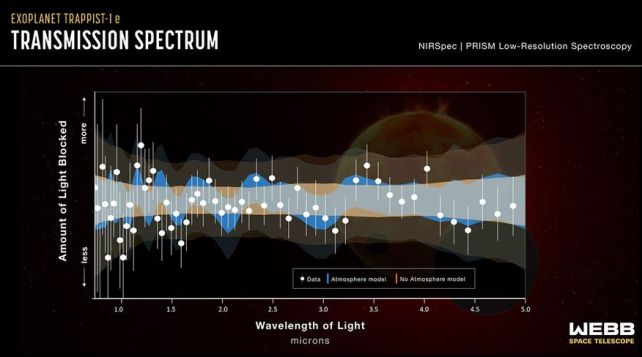

A team led by astronomer Néstor Espinoza of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and Natalie Allen of Johns Hopkins University in the US used JWST to study the starlight from TRAPPIST-1 as TRAPPIST-1e moved across its face. The team searched for changes that could indicate not just the presence of an atmosphere, but what it is made of.

A second team led by astrophysicist Ana Glidden of MIT then interpreted the results to find out what they could mean.

The team collected four transits and got to work analyzing the data – a process complicated by the need to correct for any contamination introduced by the activity of the star.

The results are almost frustratingly ambiguous, providing just enough incentive to look further.

“We are seeing two possible explanations,” says astrophysicist Ryan MacDonald of the University of St Andrews in the UK. “The most exciting possibility is that TRAPPIST-1e could have a so-called secondary atmosphere containing heavy gases like nitrogen. But our initial observations cannot yet rule out a bare rock with no atmosphere.”

If the exoplanet does have an atmosphere, Glidden and her colleagues have performed the first steps towards identifying what might be in it.

As starlight travels through a planetary atmosphere, some wavelengths can be absorbed and re-emitted by atoms and molecules making up its gases. By looking for darker and lighter parts of the spectrum, scientists can figure out what those atoms and molecules are.

The results lean away from a high concentration of carbon dioxide, which would rule out atmospheres similar to those of Venus and Mars. Nor do the results favor an atmosphere rich in the hydrogen isotope deuterium with strong carbon dioxide and methane elements.

However, the spectrum is consistent with an atmosphere rich in molecular nitrogen, with trace amounts of carbon dioxide and methane.

This is pretty tantalizing. Earth’s atmosphere is roughly 78 percent molecular nitrogen. If the results can be validated, TRAPPIST-1e might just be the most Earth-like exoplanet discovered to date. That is not a small if, though. Luckily, more JWST observations are in the pipeline, and the researchers should be able to validate or rule out an atmosphere very soon.

“We are really still in the early stages of learning what kind of amazing science we can do with Webb. It’s incredible to measure the details of starlight around Earth-sized planets 40 light-years away and learn what it might be like there, if life could be possible there,” Glidden says.

“We’re in a new age of exploration that’s very exciting to be a part of.”

The research appears in two parts in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. They can be found here and here.

Source link