Getty Images

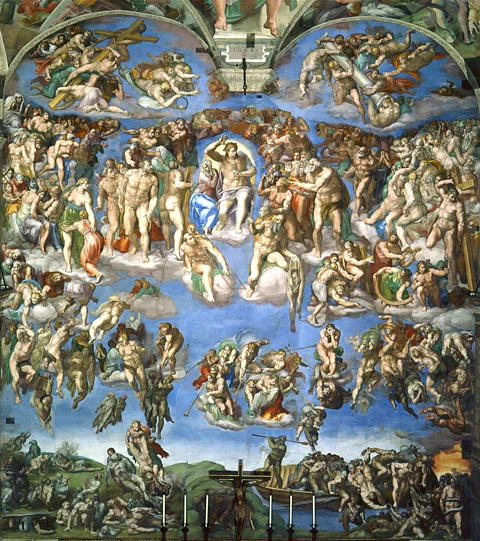

Getty ImagesIn retrospect, Michelangelo’s fresco got off rather lightly. Not long after Volterra began preserving the modesty of figures in The Last Judgment with strategically positioned drapery, Protestant iconoclasts swept through the Low Countries in 1566 and attacked Antwerp’s cathedral, permanently mutilating a grand altarpiece by Frans Floris, the city’s leading artist. Floris’s fantastical Fall of the Rebel Angels, painted just 12 years earlier, depicts a saint casting out a swarm of grotesque demons. Reformers, convinced that the triptych’s imagery violated new civic laws against superstition and idolatry, ripped the wings from the work’s hinges and destroyed its two side panels. Only the central section of the triptych, relatively free of the offending iconography, survived the demolition. When Catholic rule returned 20 years later, the salvaged fragment was rehung in the cathedral, a symbol of art’s remarkable resilience.

A powerful erasure

Not every work punished for its alleged violation of law has suffered irreparable damage. In 1815, Francisco de Goya’s famous pair of paintings depicting the same reclining woman in mirroring poses – one nude, the other clothed – was seized by the Inquisition and sequestered for decades, though neither was ultimately damaged nor destroyed. The works, known as The Two Majas, were painted between 1797 and 1800 and are revolutionary in their sensual portrayal of a contemporary woman gazing directly at the viewer, unconnected to any myth or narrative from history or religion.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter the works’ owner, the Spanish Prime Minister Manuel Godoy (who kept the canvases in a cabinet with other nude paintings), was overthrown in 1808, an investigation was opened into his possession of the scandalous portraits, which were accused of breaking laws of decency and public morality. Goya was summoned to explain himself, though the record of his defence has not survived. While Goya, who held a high position as court painter, does not seem to have been punished, his works were confiscated and kept from public view until 1836 and eventually transferred to the Prado Museum in 1901.

Source link