In a theory that challenges what we know about aging, João Pedro de Magalhães, a molecular biogerontologist at the University of Birmingham, suggests humans may be biologically capable of living much longer than we do now—possibly 1,000 years or more. But there’s a catch: we may have evolved to age faster, and the reason traces back to the Age of Dinosaurs.

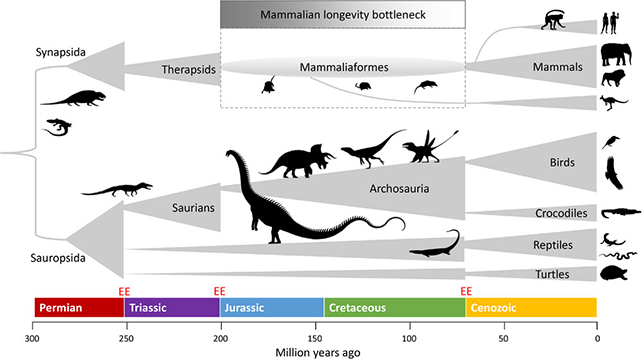

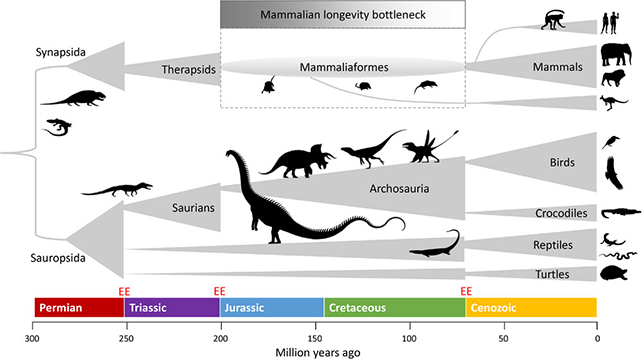

In a paper published in BioEssays, de Magalhães proposes the “longevity bottleneck” hypothesis. According to his research, early mammals were under intense pressure to reproduce quickly and survive while dinosaurs dominated the food chain. This evolutionary stress may have led them to shed certain genetic traits that once supported longer lifespans. Over time, these genetic losses became embedded in mammalian biology—including ours.

He explains: “Some of the earliest mammals were forced to live towards the bottom of the food chain… evolving to survive through rapid reproduction.” That adaptation, he believes, permanently altered how mammals—humans included—experience aging.

The Loss of Key DNA Repair Systems May Be Why We Age Faster

Part of de Magalhães’s theory involves the loss of enzymes that repair damage from ultraviolet light, such as photolyases. These enzymes are absent in most mammals, including humans, and are believed to have disappeared from our genome during the dinosaur era. The loss may be linked to nocturnal behaviors adopted by early mammals as a way to avoid predators—reducing the need for UV protection, but also cutting out a powerful DNA-repair mechanism in the process.

“It’s an example of a repair and restoration mechanism that we would otherwise have had,” de Magalhães explains. While speculative, this idea raises important questions about how long we could live if these repair mechanisms had remained intact.

He also points to other species for comparison. Some reptiles, like alligators, can regrow teeth continuously, while humans cannot—a possible result of evolutionary trade-offs that favored speed over longevity. These patterns suggest we may have lost multiple regenerative features across our evolution.

Animals Like Naked Mole Rats and Bowhead Whales Show What’s Possible

Despite these evolutionary setbacks, some mammals still manage to live extraordinarily long lives—and that’s where de Magalhães sees potential. He’s spent much of his career studying species with exceptional longevity, including bowhead whales, which can live over 200 years, and naked mole rats, known for their resistance to cancer and cellular decay.

These animals offer genetic blueprints that could inspire new ways to extend human lifespan. For example, the bowhead whale is known to repair its DNA more efficiently than humans, which may help it avoid diseases associated with aging. Naked mole rats also exhibit unique cellular behavior that seems to prevent many age-related illnesses.

According to de Magalhães, understanding these mechanisms could help us design treatments to slow or even reverse aging in humans. “We must learn to repair DNA and reprogram cells for a radically different aging process,” he said in a statement to ScienceAlert.

The Future of Aging May Look More Like Treating a Disease

De Magalhães draws a direct comparison between aging and diseases that once seemed untreatable. He notes that his great-grandfather died from pneumonia in the early 20th century—a common cause of death at the time. Today, a simple dose of penicillin could have saved him.

His point: aging may one day be manageable in the same way, using therapies that target the biological processes behind it. One promising candidate is rapamycin, a compound already used in medicine to prevent organ rejection. Studies show it can extend the lifespan of certain mammals by 10 to 15 percent, and scientists are now exploring its broader anti-aging potential.

“I’m optimistic,” de Magalhães said. “We’ll develop medications similar to statins that people take daily—not for cholesterol, but for longevity.” Even a modest slowdown in the aging process—by just 5 to 10 percent—could have a major impact on public health, potentially delaying the onset of conditions like dementia, stroke, and cancer.

Source link