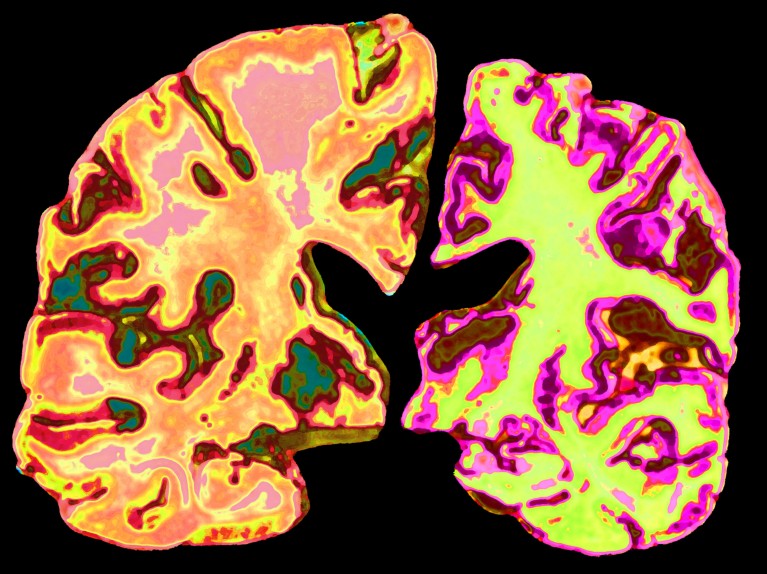

A slice from a normal human brain (left, artificially coloured) contrasts with a slice from the brain of a person with Alzheimer’s disease.Credit: Jessica Wilson/Science Photo Library

Replenishing the brain’s natural stores of lithium can protect against and even reverse Alzheimer’s disease, suggests a paper published1 today in Nature.

The paper reports that analyses of human brain tissue and a series of mouse experiments point to a consistent pattern: when lithium concentrations in the brain decline, memory loss tends to develop, as do neurological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease called amyloid plaques and tau tangles. The study also found evidence in mice that a specific type of lithium supplement undoes these neurological changes and rolls back memory loss, restoring the brain to a younger, healthier state.

A man was destined for early Alzheimer’s — these genes might explain his escape

“This is groundbreaking,” says Ashley Bush, a neuroscientist at the University of Melbourne in Australia, who was not involved in the study. “We only recently have the first disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer’s disease. But they only target one thing: the amyloid plaques. This approach targets all the major pathologies of concern in the disease.”

If confirmed in clinical trials, the implications could be profound. Dementia affects more than 55 million people globally; most have Alzheimer’s disease. Anti-amyloid therapies on the market slow cognitive decline, but “they don’t stop it. They don’t restore function,” says co-author Bruce Yankner, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

“We don’t yet have the penicillin for Alzheimer’s,” he says.

Old tonic, new role

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, lithium was touted as a mood-altering health tonic, even appearing as an upper in an early recipe for 7-Up. It re-emerged in the 1970s as the gold-standard treatment for bipolar disorder. Scientists soon noticed that among people with bipolar disorder, brain ageing was slower in those taking lithium than in those who weren’t. Meanwhile, epidemiological studies revealed that regions in which water supplies contained trace amounts of lithium had relatively low dementia rates2. But clinical trials to test lithium’s effects on cognitive decline had mixed results.

In research to clarify lithium’s role, Yankner and his team showed, for the first time, that the metal is naturally present in the brain — where it has an important physiological role.

The clues added up. The authors found that lithium levels were lower in parts of the human brain affected by Alzheimer’s disease than in unaffected regions. The team also discovered that in people with mild cognitive impairment, a precursor to Alzheimer’s, brain lithium is tied up in amyloid plaques, leaving less available for essential brain functions. This lithium withdrawal “became more severe as the disease progressed”, says Yankner. Lithium met a similar fate in the brains of mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease.

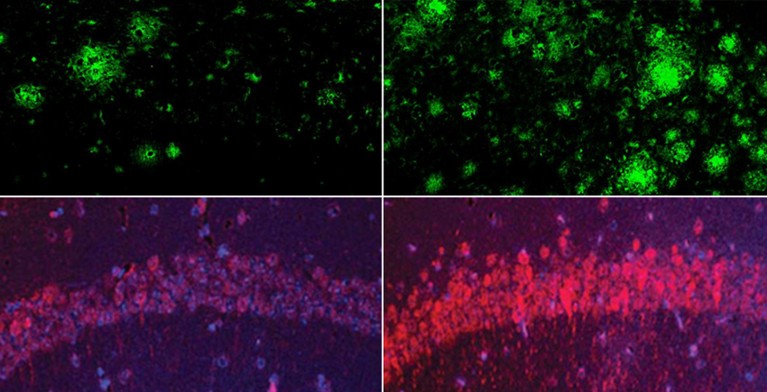

A mouse with normal lithium levels in its brain had fewer amyloid plaques (top left) and tau tangles (bottom left) than did a mouse with lithium deficiency (top and bottom right). Credit: Yankner Lab

In further experiments using the mice, those with lithium-deficient brains developed more plaques than did animals with normal lithium levels. This kicked off a vicious cycle that might represent the devastating progression of Alzheimer’s disease: less lithium in the brain leads to more amyloid, which leads to even less lithium.

Yankner and his team linked lithium loss with other markers of the disease, including a build-up of tau protein tangles and altered activity of Alzheimer-related genes. They even identified a potential means to break the deleterious cycle.

Most clinical trials of lithium have tested the form lithium carbonate. The team showed that amyloid plaques readily trap this form — but others, such as lithium orotate, avoid that fate. When the authors gave mice low doses of lithium orotate, it reversed disease-related brain damage and restored the animals’ memory. Lithium carbonate did not have the same benefits, potentially helping to explain the mixed results of earlier clinical trials.

Source link