Wholesale electricity costs as much as 267% more than it did five years ago in areas near data centers. That’s being passed on to customers.

“We can’t figure out why it has increased so much.”

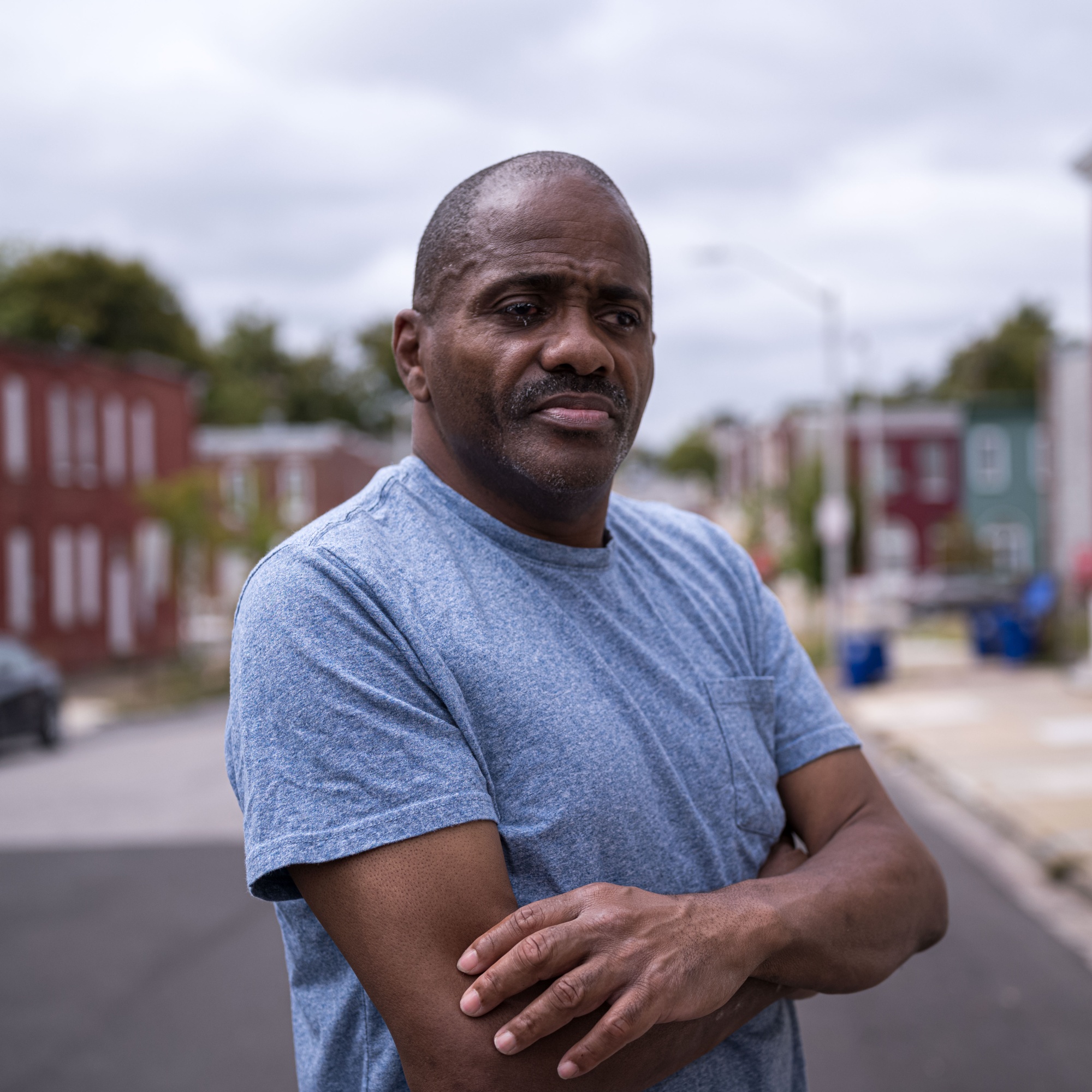

Kevin Stanley, of Broadway East, Baltimore

“No way I could continue to pay that kind of bill.”

Nicole Pastore, of Guilford, Baltimore

“It’s killing my pockets.”

Antoinette Robinson, of Greenmount East, Baltimore

Data centers are proliferating in Virginia and a blind man in Baltimore is suddenly contending with sharply higher power bills.

The Maryland city is well over an hour’s drive from the northern Virginia region known as Data Center Alley. But Kevin Stanley, a 57-year-old who survives on disability payments, says his energy bills are about 80% higher than they were about three years ago. “They’re going up and up,” he said. “You wonder, ‘What is your breaking point?’”

It’s an increasingly dramatic ripple effect of the AI boom as energy-hungry data centers send power costs to records in much of the US, pulling everyday households into paying for the digital economy.

The power needs of the massive complexes are rapidly driving up electricity bills — piling onto the rising prices for food, housing and other essentials already straining consumers. That’s starting to have economic and political reverberations across the country as utilities and local officials wrestle over how to divvy up the costs. Yet those same facilities are a linchpin of US leadership in the global AI race.

A Bloomberg News analysis of wholesale electricity prices for tens of thousands of locations across the country reveals the effects of the AI boom on the power market with unprecedented granularity. The prices were tracked and aggregated monthly by Grid Status, an energy data analytics platform. Bloomberg analyzed this data in relation to data center locations, from DC Byte, and found that electricity now costs as much as 267% more for a single month than it did five years ago in areas located near significant data center activity.

About two-thirds of the power consumed in the US runs off of a state or regional grid, where the system operator manages the trading of energy. These wholesale commodity costs are passed on to households and businesses on their utility bills, which then include other charges to maintain and expand the network. That can affect even customers who aren’t in close proximity to a data center, since their energy relies on the same grid.

Every day, wholesale electricity prices are measured in real time by Locational Marginal Pricing points on the power grid, called nodes. LMPs are primarily made up of the cost to produce the energy and congestion. Analyzing data from 25,000 nodes used by seven regional transmission authorities, Bloomberg News estimated how much wholesale prices in the lower 48 states have changed since 2020.

In 2020, wholesale electricity prices around the country hovered around $16 per megawatt-hour, on average, with slight variations from one energy market to the next.

In 2025, electricity costs depend far more on where you’re located. Prices are high in many parts of the country, while some central states have negative wholesale prices, meaning more electricity is produced than consumed.

Wholesale prices more than doubled since 2020 in some markets, but the increases aren’t felt equally. Many areas with the biggest jumps — like Baltimore — are near data center hot spots.

Of the nodes that recorded price increases, more than 70% are located within 50 miles of significant data center activity.

Source: Bloomberg News analysis of data provided by Grid Status and DC Byte

Note: Prices shown are the average wholesale electricity prices, based on the median prices of all the nodes within a given 100 square-mile area. To determine significant data center activity, a dynamic threshold was used that took into account the total data center capacity in the area around any given LMP node. The map displays results for the month of April, a time when grids generally don’t face additional pressure from extreme weather events. For areas where the median electricity price switched from positive to negative, we considered the change as –100%. For more details, see the full methodology note.

Tech companies, now among the biggest and most powerful forces in the world, have staked their future on AI. Data centers — some with a footprint large enough to cover much of Manhattan — are chock full of racks of servers delivering computer power and storage needed to train and run models.

Their power needs are only set to accelerate. In recent weeks alone, Nvidia Corp. said it will invest as much as $100 billion in OpenAI to support new data centers, while Microsoft Corp. struck a multiyear deal worth almost $20 billion to get cloud computing power from Amsterdam-based Nebius Group NV using a New Jersey data center. OpenAI and Oracle Corp. forged a partnership to build 4.5 gigawatts’ worth of data center capacity, enough energy to power millions of American homes.

“The reliability crisis is here now; it’s not off in the distance somewhere,” said Mark Christie, a former chairman of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission who also served as a long-time Virginia regulator. He said that load forecasts — the expected demand for power on electricity grids — are a key factor pushing up costs, driven by the data center interconnection requests.

The affordability problem extends beyond US borders. Power auction prices in Japan hit all-time highs amid government expectations of an AI boom, while Malaysia is lifting electricity rates for data centers as new facilities tighten supply. In the UK, a report from Aurora Energy Research found that higher demand from data centers could push power prices up 9% by 2040.

Globally, data centers are expected to consume more than 4% of electricity by 2035, according to BloombergNEF. Put another way: If the facilities were a country they’d rank fourth in electricity use, behind only China, the US and India.

In the US, power demand from data centers is set to double by 2035, to almost 9% of all demand, according to BNEF. Some predict it will be the biggest surge in US energy demand since air conditioning caught on in the 1960s. That comes as the grid is already struggling to update aging infrastructure and adapt to climate change.

“Without mitigation, the data centers sucking up all the load is going to make things really expensive for the rest of Americans,” said David Crane, chief executive officer of Generate Capital and a former energy official in the Biden administration. All that demand risks brownout situations in some US power markets within the next year or two, he said.

President Donald Trump, who won election in part because of Americans’ dissatisfaction with higher consumer costs, said on the campaign trail that he would cut electricity prices in half within 18 months of taking office. Yet prices have only risen since his inauguration. His energy chief said this month that soaring power bills are now his biggest concern.

The president has championed America’s AI dominance while also stripping support for new sources of energy like solar and wind farms with his One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which some experts say will increase average household energy bills. BNEF forecasts that annual deployment of new solar, wind and energy storage facilities in 2035 will be 23% lower than it would have been without the bill.

Trump has instead focused on unlocking power through expanding the use of coal, natural gas and nuclear energy. In a statement, White House spokeswoman Taylor Rogers blamed the Biden administration’s climate agenda and “destructive” policies for driving up energy prices.

“President Trump’s actions to unleash American energy are the only reason our country has not experienced blackouts and grid failures that would have occurred” under the prior policies, she said.

“They can say this is going to help with AI, but how is that going to help me?”

Kevin Stanley sitting on his stoop in Baltimore on Sept. 10.

PJM Interconnection, the operator of the largest US electric grid, has faced significant strain from the AI boom. The rapid development of data centers relying on the system raised costs for consumers from Illinois to Washington, DC, by more than $9.3 billion for the 12 months starting in June, according to the grid’s independent market monitor. Costs will go up even more next year.

Demand tied to the cryptocurrency boom, new factories and the electrification of the economy, including vehicles and home heating, are also pushing up power bills. The cost of natural gas, the No. 1 power-plant fuel in the US, is increasing thanks to all of this demand. And in the zone that includes Baltimore, the planned retirement of coal plants has increased the price of power by decreasing projected supply.

Baltimore residents saw their average bill jump by more than $17 a month after a power auction held by PJM reached a record high, according to Exelon Corp.’s Baltimore Gas & Electric utility. This year’s auction set another record, which will boost the average power bill in Baltimore again by up to $4 starting in mid-2026.

Read more of Bloomberg’s coverage on how data centers are impacting communities globally:

AI Is Already Wreaking Havoc on Global Power Systems

AI Needs So Much Power, It’s Making Yours Worse

AI Is Draining Water From Areas That Need It Most

There has been a “massive outcry about high energy bills” in the area, said David Lapp of the Maryland Office of People’s Counsel, an independent state agency that advocates for residential utility customers. His office fields about 50 calls a week and recently hired a new staffer to help manage the requests for help. A comic strip taped to his office door makes a dark joke about AI causing the power grid to collapse.

Nicole Pastore, who has lived in her large stone home near Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University campus for 18 years, said her utility bills over the past year jumped by 50%. “You look at that and think, ‘Oh my god,’” she said. She has now become the kind of mom who walks around her home turning off lights and unplugging her daughter’s cellphone chargers.

And because Pastore is a judge who rules on rental disputes in Baltimore City District Court, she regularly sees poor people struggling with their own power bills. “It’s utilities versus rent,” she said. “They want to stay in their home, but they also want to keep their lights on.”

Stanley’s neighborhood is a mix of well-tended houses like his and those that are condemned or abandoned, with broken windows and holes in the walls. He used to work as a hotel manager but glaucoma took his vision almost 20 years ago, leaving him with few employment options.

“They can say this is going to help with AI, but how is that going to help me?” he said from his front steps. “How’s that going to help me pay my bill?”

The analysis of 25,000 LMP nodes examined the relationship between the change in wholesale electricity prices and the nodes’ distance from data centers. LMP nodes with increases are more likely to be concentrated near data centers, the analysis shows.

Electricity Price Increases Are Concentrated Near Data Centers

Distance from significant data center activity for LMP nodes and change in the median wholesale electricity prices from 2020 to 2025

Source: Bloomberg News analysis of data provided by Grid Status and DC Byte

Note: The analysis includes a small number of nodes in Canada used by US RTOs. Median distances rounded to the nearest whole number. To determine significant data center activity, a dynamic threshold was used that took into account the total data center capacity in the area around any given LMP node. For more details, see the full methodology note.

The boom highlights a stark trade-off: Data centers devour electricity and water, but also are required for the tech-driven conveniences of the modern era, whether it’s using ChatGPT for queries, getting matched with an Uber driver or seeing streaming recommendations on Netflix. Even some activists who protest widespread development of the facilities acknowledge that their digital lives rely on them.

In 2024, the three biggest US cloud providers — Amazon.com Inc., Microsoft and Alphabet Inc.’s Google — spent more than $200 billion on capital expenditures, most of it to construct data centers. To ease the pressure, tech companies are working on ways to speed additional power capacity to the grid while developing better techniques for cooling data centers and chips that use less energy. Hyperscalers are collectively bringing back old reactors, spurring upgrades at existing plants and investing in next-generation nuclear power.

In some US regions it’s clear that data centers are a major influence on the surge in energy costs. They are the largest source of new power consumption in Texas by far. Dominion Energy Inc. — which serves northern Virginia’s Data Center Alley — forecast that its peak demand would rise by more than 75% by 2039 with data centers. It would be just 10% without. Against that backdrop, power costs have become a key issue in this year’s gubernatorial elections in Virginia and New Jersey.

Utilities across the US say they are trying to ensure tech firms pay a fair share for the electricity and infrastructure upgrades their data centers require. Some power companies have moved to require tech firms to put up more collateral or pay for specific amounts of electricity, even if they end up using less.

Data centers in various stages of construction in Ashburn, Virginia on Sept. 10.

“We believe data centers should pay for the full cost of their power,” Dominion spokesperson Aaron Ruby said in an email. “That’s how we design our rates, and it’s the standard our regulator uses in reviewing them.” Ruby added that infrastructure costs are allocated based on how much it costs to serve each group of customers, with data centers paying an increasingly large percentage of transmission costs.

Calvin Butler, the CEO of Exelon, said the company is pushing for long-term solutions that are fair and bring peace of mind to customers. “While we can’t control every factor driving up prices, we refuse to stand by,” he said in a statement.

For local officials, the effects are becoming urgent. Last week, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro convened the first-ever meeting of representatives from all 13 states served by PJM. Shapiro, a Democrat, warned that if PJM didn’t tackle changes to reign in consumer costs, Pennsylvania could withdraw from the system. New Jersey regulators are studying this and Maryland may do the same, underscoring growing discontent among the three original states that made up the P, J and M grid.

PJM has said that supply and demand conditions are driving up prices. A spokesman declined to comment further.

As a regional grid operator, PJM not only runs daily markets to trade electricity but is also responsible for transmission planning, and costs for those projects are socialized within the grid. It approved $5.9 billion in new transmission projects in February, attributing the load growth primarily to data centers. PJM also runs a capacity auction to contract to procure power supplies where consumers pay billions of dollars a year to generators to ensure they are available.

“The PJM capacity market will be at its maximum price for the foreseeable future, it could be five or 10 years,” said Joe Bowring, president of Monitoring Analytics, the grid’s official watchdog. He said data centers need to bring their own generation, and those projects should get a speedy approval process.

Data Centers Consume a Growing Share of Electricity

Share of total electricity consumption estimated to be used by data centers for a sample of US states

Source: Bloomberg News analysis of data from DC Byte and the US Energy Information Administration

Note: States shown are those where data centers accounted for 5% or more of total electricity consumption in 2024, the most recent year with full data available. For more details on how data center consumption is estimated, see the full methodology note.

Some local governments are now rethinking how utility costs are shared and who should pay. In Oregon, lawmakers in June passed the POWER Act, a law designed to help utilities strike fairer deals with data centers and crypto miners.

The issue is especially pronounced in the Portland suburb of Hillsboro, where 15 major data centers are located. Nearly all of Portland General Electric’s load growth has come from commercial customers, said Bob Jenks, executive director of the Oregon Citizens’ Utility Board. Yet over the past decade, residential rates climbed by 8 cents per kilowatt-hour, compared with just 2 cents for large users, he said. Rising home power costs contributed to a wave of electricity shutoffs during a frigid winter last year.

Portland General said there are numerous factors in rate increases. The utility is hoping to have new rates based on the POWER Act for the commission to approve next year “to keep prices as low as possible for our residential and small business customers while supporting growth of data centers as they continue to come online,” said John McFarland, vice president and chief commercial and customer officer.

The POWER Act was designed to give regulators sharper tools to hold large electricity users accountable, said State Representative Pam Marsh, who introduced the bill. She noted that Amazon was collaborative on the legislation, though it ultimately withheld final support. Google did as well.

An Amazon spokesperson said the company works closely with utilities and grid operators to plan for future growth. When special infrastructure is needed, “we work to make sure that we’re covering those costs and that they aren’t being passed on to other ratepayers,” the spokesperson said.

Google supports paying its fair share for electricity to data centers and helping to protect other rate payers, according to a spokesperson. The company said it has been working to use less electricity even as it expands data centers, with Google’s operations delivering more than six times more computing power per unit of electricity than they did five years ago.

A similar debate is underway in the political battleground state of Wisconsin, where Microsoft is developing a massive data center on land once meant to be a plant for Foxconn, until the iPhone supplier dramatically scaled back its highly touted plans. Local residents are already paying higher bills tied to power lines built for Foxconn, according to Tom Content, executive director of the state’s Citizens Utility Board.

Now, with Microsoft’s site requiring 900 megawatts — and an even larger 1.3-gigawatt facility that could go up to 3.5 gigawatts approved for construction farther north — utility We Energies and its parent company told investors it will need to boost its power capacity by about 20% through 2029. The utility, which plans investments to bring 6 gigawatts of new generation online in that time period, has proposed tariffs that force “very large” customers to shoulder the costs of infrastructure built for them, even if they later give up on the project.

Microsoft says it collaborated with the utility in structuring the proposed tariffs.

“We recognize that it’s literally our responsibility to make sure that when we come to a community, when we get connected to a grid, that the cost of the infrastructure that is being dedicated to us, that those costs of service, get allocated to us,” said Bobby Hollis, Microsoft’s vice president of energy.

Still, Milwaukee resident Montre Moore, first vice president at the county chapter of the NAACP, is worried about the impact of future rising prices on the area’s poor and communities of color. His own home heating bill rose from around $118 a month to $160 last winter, and he expects another hike this year. “We are in for a world of hurt that is coming from a rate perspective and from an environmental perspective,” he said.

We, in a statement, said its typical bills are in line with other Midwest utilities, and that its most recent rate approved by regulators wasn’t tied to data centers and instead was related to issues including programs for severe weather and costs from previous projects.

In northern Virginia, Dominion Energy cited data center demand, inflation and higher fuel costs when asking regulators to raise its customer bills by about $20 a month for the average residential user over the next two years. Customers wrote Dominion’s regulators to complain.

One woman from Hampton said she’s an 81-year-old widow with limited income and can’t afford the increase. Another from Virginia Beach said she and her husband are already living paycheck to paycheck. A man in Midlothian said data centers shouldn’t push up bills if they’re not paying their fair share.

Mary Ruffine in her home in Arlington, Virginia on Sept. 11.

Mary Ruffine was shocked to see her monthly bill increase to around $260 from roughly $200. She lives in Arlington, Virginia, an affluent Washington suburb with tree-lined streets shading homes. Her monthly bill increases don’t mean she has to skimp on medication or skip meals. But she doesn’t like that poorer people are shouldering higher bills while some of the richest companies in the world profit.

“I just feel like we are sharing the burden in an uneven way with these corporations that have billions of dollars,” she said. “And so we the people are the ones who are absorbing the costs for these data centers.”

Back in Baltimore, Antoinette Robinson leaned on her walker during a recent afternoon stroll to complain that her high power bills leave her with less than $100 in her bank account at the end of each month. “It’s killing my pockets,” she said.

Stanley says the trees that used to grow on his street were cut down. Without their shade his home gets even hotter in the summer, forcing him to rely more on expensive air conditioning.

The rise in his power bills has him reusing disposable razors 20 times and stretching the supplies for his diabetes and sleep apnea. Sometimes he goes to food banks.

“People shouldn’t have to decide between their gas and electric bill and food,” he said.

.jpg?w=3800&h=2000)