When Dan Jackson took the reins of the Austin, Texas, police department’s unsolved homicide unit in 2022, his boss approached the detective with a sense of urgency.

“My first day on the job, my supervisor asked me to come into his office and shut the door,” Jackson said. “I thought I was already in trouble, for some reason.”

Jackson wasn’t in trouble, but he was given serious marching orders: Solve the murders of four teenage girls in a yogurt shop that traumatized the community and shocked Texans over three decades ago.

“I knew at that point … the gravity of the case, how big it was at that point, it would be with me the rest of my life,” Jackson told CNN in an exclusive interview. “This is my career from now on … Even if it’s solved, I’ll still be with it forever.”

So dogged was Jackson’s subsequent pursuit of justice, even being shot in the line of duty didn’t stop him from staying on the case, highlighted in an HBO documentary released in August called “The Yogurt Shop Murders.”

Three years later, thanks to a combination of improved DNA technology, ballistics testing, assistance from in-state and out-of-state law enforcement and fortuitous timing, Jackson’s persistence since that meeting with his supervisor has paid off.

The case finally has been solved, but for a few loose ends, Jackson said.

Robert Eugene Brashers, a suspected serial killer linked to multiple deaths and rapes across the country who died in 1999, was identified on Monday as the man likely responsible for the deaths of the four girls in Austin in 1991.

“I’m 100% that this is Robert Eugene Brashers,” Jackson told CNN.

The findings also effectively means the exoneration of four teenage boys initially implicated in the killings in 1999, two of whom confessed. The two who confessed – and later recanted – were convicted of capital murder and remained in prison until DNA evidence proving their innocence led to their release in 2009, prosecutors said.

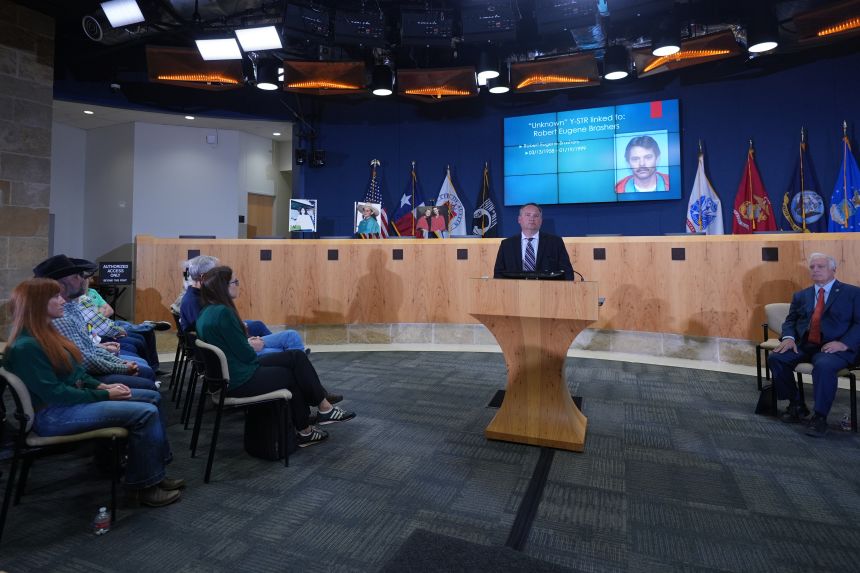

“The overwhelming weight of the evidence points to the guilt of one man and to the innocence of four,” Travis County District Attorney Jose Garza said at a news conference Monday, noting the Austin police investigation into the murders remains ongoing nonetheless.

“They say it’s when Austin lost its innocence, and we had all these questions for all these years,” Jackson said of the murders. “The community can maybe start to heal now that we know.”

Jackson grew up about 30 miles south of Austin and knew about the case since he was a boy.

“I was about eight or nine months younger than Amy,” the youngest of the four victims. “So, I remember all this happening, I remember growing up with it.”

Around closing time, just weeks before Christmas in 1991, Eliza Thomas and Jennifer Harbison, both 17, were finishing up work at the “I Can’t Believe It’s Yogurt” store when Jennifer’s 15-year-old sister Sarah and her 13-year-old friend Amy Ayers came to meet them.

An unknown man entered the store and tied the girls up with their own clothing and shot all four in the head execution style. There was evidence of sexual assault in three of the four victims, but almost all of the physical evidence was lost because the building was then set on fire.

Law enforcement had little to work with and forensic evaluation with DNA was still an emerging technology.

It wasn’t until 2008 that swabs from a sexual assault kit in the case developed an unknown male Y-STR DNA profile, but the science was not fully developed at that point and did not produce any answers. This Y-STR (Y-chromosome Short Tandem Repeat) DNA is only found from males, is unique to that person and, although not conclusive, can help law enforcement find a suspect.

In 2018, because of advancements in technology, the unknown Y-STR DNA was submitted for retesting, getting more sophisticated results but still no name of a possible suspect.

When he took on the case in 2022, Jackson was anxious to do more testing but also knew the science had to catch up.

“DNA has come a long way since ’91, and even just the last couple of years it’s made huge strides of what we can and can’t do,” he said.

The next year Jackson suffered a personal and professional setback.

On August 6, 2023, Jackson volunteered to help out on patrol one night – and wound up getting shot during an encounter with an armed suspect.

“I got shot mostly in the right arm, but a little bit to the face, with a 12-gauge shotgun, from about 10 feet away,” he said.

Surgery, then rehab, then finally Jackson was put on light duty.

Jackson picked the cold case right back up but had to dispatch colleagues to do the voluminous number of necessary interviews and to pursue any new tips.

“You just keep going,” he said.

In late June of this year, Jackson thought about re-testing the one spent .380 casing found in the yogurt shop’s floor drain. It was the only physical evidence found at the crime scene.

The victims had been shot with .22 caliber bullets, but Amy was the only one who was also shot with a .380 caliber bullet.

Jackson resubmitted the .380 bullet casing to the National Integrated Ballistic Information Network, or NIBIN system, that categorizes shell casing markings nationwide.

Within hours of his submission, Jackson got a call from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives on July 2.

“I’m sitting down on the beach,” on a family vacation, Jackson recalled. “He’s like, ‘Do you have a drink in your hand? I was like, ‘I have a drink in my hand.’ He said, ‘Good … You’re gonna need it.’ And he goes, ‘We got a hit.’”

“I just couldn’t believe it.”

The bullet casing had the same tool markings – unique individual indentations that guns produce on casings once they have been expended – to a gun used in an unsolved murder in Kentucky in 1998.

Kentucky officials have not announced any developments in the case publicly, but Jackson said the Texas murders shared similar details.

“I was confident that these were related … but we didn’t have a name,” he said.

In August, Jackson broadened his request for similar Y-STR DNA profiles to law enforcement agencies throughout the country. A South Carolina lab confirmed on August 22 that it had a complete Y-STR match to Jackson’s unknown DNA.

The South Carolina DNA profile was from a 1990 Greenville sexual assault and murder case that had been solved.

“It was pretty surreal. It’s still surreal,” Jackson said.

Even before calling South Carolina authorities for confirmation, Jackson went to the internet in hopes of finding the suspected killer’s identity.

“I googled the date of offense, Greenville, South Carolina, and that’s when Robert Brashers’ name as a serial killer popped up,” Jackson said.

In a subsequent phone call with a detective in South Carolina, Jackson was stunned to hear of one particular similarity between his case and theirs.

“He said, ‘Hey, let me ask you something. Did he tie the victims up with their own clothing?’ And that’s when the hair in the back of my neck stood up,” Jackson said. “I was like, we’re on the right path and I said, ‘Yeah, he did that in my case, too.”

At that point, Jackson found out that Brashers, 40, had killed himself in 1999 during a police standoff.

Years after his death, investigators through DNA and ballistics determined Brashers was responsible for multiple crimes in the 1990s – ranging from shootings to sexual assaults to murder – in Tennessee, Missouri, and South Carolina. Among those killed were a woman in South Carolina in 1990 and a mother and her 12-year-old daughter in Missouri in 1998, authorities said.

A fake obituary and a real wedding

It turned out Brashers’ criminal history dated to at least 1985, when he tried to kill a woman in Florida, Jackson said.

“He attacked a woman when he tried to make sexual advances of her and she refused,” Jackson said. “He ended up shooting her four times – four times – and somehow, she lived.”

Brashers was sentenced to 12 years in that case and granted parole four years later, according to Jackson.

One reason he never got caught for many of his crimes was that he worked to outfox the system using many fake names and aliases, Jackson said.

“He used combinations of family members’ names. He used his brother’s name, date of birth,” Jackson said.

“He had published an obituary for himself at one point.”

The obituary didn’t prove to be too effective, Jackson said, because a short time later he was listed as a groomsman in the same newspaper.

Ultimately, Jackson learned the name of a possible suspect through the use of genetic genealogy that had been done in South Carolina in 2018. At that time, DNA collected in the 1990 South Carolina murder case identified Brashers as the suspect. A judge then ordered Brashers’ body to be exhumed in Arkansas to extract his DNA from a bone sample to confirm that match.

Steve Kramer, a former attorney for the FBI, who developed the science of genetic genealogy, said in an email “the case solution also relied on Investigative Genetic Genealogy (IGG) which was first used in a criminal case in 2018 with the Golden State Killer case in California.”

Kramer was brought into the yogurt shop murders case in late 2022 to be a part of the investigative team to sort through the evidence and find DNA.

“For the last three years this group spoke nearly every month about the evidence, new techniques and potential new methods to solve the case. The group regularly met with many different labs across the country to inquire about possible ways to proceed,” Kramer said.

“What was incredibly unique about the solution in this case is that it required the combination of multiple techniques both old and new,” he said.

It required genetic genealogy, ballistics, “Y-chromosome DNA which is only used in a handful of states” and “the use of a DNA profile used by the FBI’s CODIS software, which has been the standard DNA profile since the 1990s,” Kramer said.

Jackson felt like he had his man but he needed to know why Brashers was in Texas and where he went after the yogurt shop murders.

Jackson ran a background check on Brashers and found that 48 hours after the Austin murders he was stopped by Border Patrol at the Texas/New Mexico line. He was driving a stolen car and was carrying a .380 caliber weapon, Jackson said.

It was the same model that killed Amy, Jackson said.

The gun Brashers had at the Texas border crossing on December 8, 1991, matched the ballistics of the gun used at the yogurt shop, Jackson said, which matched the ballistics of the gun used later in Kentucky. The same gun was used when he killed himself in Missouri, Jackson said.

Last month, Jackson decided it was the right time to do a direct comparison of unknown male DNA found under Amy’s fingernails.

Usable DNA would be consumed during the testing so it was a risk, but it was now or never.

“This is it,” Jackson said. “We’re gonna push our chips. We’re going all in.”

On Sept. 15, Jackson submitted Amy’s fingernail clippings from autopsy for testing. Unknown DNA from under her nails were directly compared to Brashers’ DNA profile, and they matched, he said.

Statistics show it’s 2.5 million to 1 that Brashers’ DNA was underneath Amy’s fingernails, Jackson said.

Given the totality of the investigative findings, Jackson encourages his counterparts across the country to look at their unsolved homicides and compare this case to theirs, as there may be more victims out there.

“If you had any unsolved murders with a similar MO … between 1989 to early 1992, especially if it’s a .380 involved, and then again in ‘97 and ‘98 when he was back out of prison, please get in contact with us,” Jackson said.

Mindy Montford, now senior counsel of the state attorney general’s cold case unit, began working on the case in 2017 when she was an assistant Travis County district attorney and pledged to the families she would never give up on it. She said her unit would continue investigating to determine whether Brashers was responsible for other violent crimes in Texas.

Jackson said solving the yogurt shop murders required a group effort, which included the Texas Attorney General’s Office Cold Case Unit, Texas Rangers, Texas Department of Public Safety, the City of Austin Forensic Science Division as well as the ATF and police departments that had cases pointing to Brashers.

Shawn Ayers lost his only sibling Amy that horrific night in Austin in 1991. He was 19 years old, and his parents had shared with him the gruesome truth about her final moments.

A number of detectives had cycled through the case by the time Jackson was assigned to it 31 years later.

Angie Ayers, Shawn’s wife, had followed the case from the beginning, when she was 16 years old, well before she met her future husband, because she knew the cousins of another victim.

Jackson was warned that Angie Ayers was a force to be reckoned with: She won’t give up.

The couple was told back in 2022 the new lead detective had a forensic background. They thought that was great because DNA testing was ramping up.

“When he came in, there was no ego,” Angie Ayers said. “It was like, ‘I’m taking on this case. I don’t want there to be another detective on it. I want to solve it.’”

Jackson backed up his words with his actions.

“He answered every call, every email, every text message,” Angie Ayers said.

“Besides being a good detective he’s a good person … That’s where it starts,” Shawn Ayers said.

Shawn and Angie Ayers were showing their horses last month in Bryan, Texas, in a competition that demonstrates the horses’ versatility in working cattle, when they got a call from Jackson: He and a team were driving up the next day to give them some important news.

Angie Ayers told people at the arena she needed a private room. The couple said the pressure of what they were or were not going to find out was intense.

Their clothes were dirty from the riding competition but, Angie said, “I jumped off the horse, unsaddled and went to that meeting.”

After they learned of the cracked cold case and the identity of the suspected killer, she said to her husband, “How awesome is this, that we get the news here at a horse show and Amy loved horses so much. It was just a message from the other side like it’s OK. And it was a really good feeling, I think, for both of us.”

Shawn and Angie Ayers said now they want to do their part to help other victims’ families of unsolved homicides get answers. They believe Amy’s killer has done this to more.

At Monday’s press conference, after Jackson explained how they caught the suspected Austin yogurt shop killer, Amy’s father, Bob, placed a pin on the detective’s lapel that had been created by the parents of the victims right after the murders and were worn around Austin.

“We Will Not Forget,” the pin reads.

“That is one of the original pins that was made … and he deserved it,” Shawn Ayers said. “It’s not much, but to us, it’s a lot.”

Ayers said they had always been told that Amy fought for her life.

“Now we have proof,” he said. “Last thing she did on this earth was fight. We’re not done … still going to fight for her and fight for other families.”

If he could talk with his sister, who helped solve this case because of the suspected killer’s DNA under her fingernails, Ayers told CNN: “I wish this hadn’t happened. I love you, but it did happen. It’s better to go out fighting on your feet than go out on your knees … and she did.”

Asked what his message would be to Amy, Jackson paused for a moment.

“I’m sorry it took 34 years to find this out for you and your parents, but good for you, girl, scratching the s**t out of him,” Jackson said.

“That’s awesome you did that because that’s what got us to where we are today.”

Source link