In 2013, Motorola tried to claw its way into a bigger share of a smartphone market dominated by Apple and Samsung with four words: Made in the USA.

“There was a segment of customers that said, ‘Hey, if you produce products in the United States, I’m more likely to consider them,” Dennis Woodside, the former CEO of Motorola and current CEO of enterprise software service provider Freshworks, told CNN.

But those efforts were short lived.

Motorola shut down the Texas factory the following year and abandoned domestic assembly of the Moto X, its then-flagship phone meant to compete with the latest iPhone and Samsung Galaxy device.

Woodside’s experience underscores why many tech products like smartphones are largely assembled in Asia and South America rather than in America. Proximity to crucial suppliers and lower labor costs are only part of the problem; it’s the gap in necessary skills and the difficulty in filling factory jobs that makes it so challenging to bring smartphone production stateside.

The conundrum Motorola grappled with more than a decade ago is suddenly relevant again as President Donald Trump pressures Apple and Samsung to make their mobile devices in the United States or face tariffs. Higher levies on imports from China, where many electronics are assembled, are set to take effect on August 12 unless the two economic powerhouses agree to a deal or an extension. India – now the world’s top exporter of smartphones to the US – will grapple with tariffs of 25% when the new rates kick in on August 7.

Woodside, who ran Motorola under Google from May 2012 until it was sold to Lenovo in 2014, has advice for any company trying to make smartphones in America today: Don’t underestimate how difficult it will be to find the right skilled workers — and keep them.

“You have to have a very strong value proposition to the employee,” he said. “You have to be thoughtful about how you use automation, and be really smart about all of the economics to make sure that at the end of the day, you can be price competitive in the market.”

The then-Google-owned tech company made an ambitious bet in 2013 to produce its Moto X smartphone in Fort Worth, Texas. Doing so not only appealed to US shoppers looking to buy domestically but also allowed the company to provide more customization than what was possible with the latest iPhone or Galaxy phone.

Through Motorola’s website, consumers could tailor certain details of the phone’s aesthetic like the color of its buttons and back panel — one of the device’s key selling points.

“To do that, you had to manufacture closer to the consumer,” Woodside said.

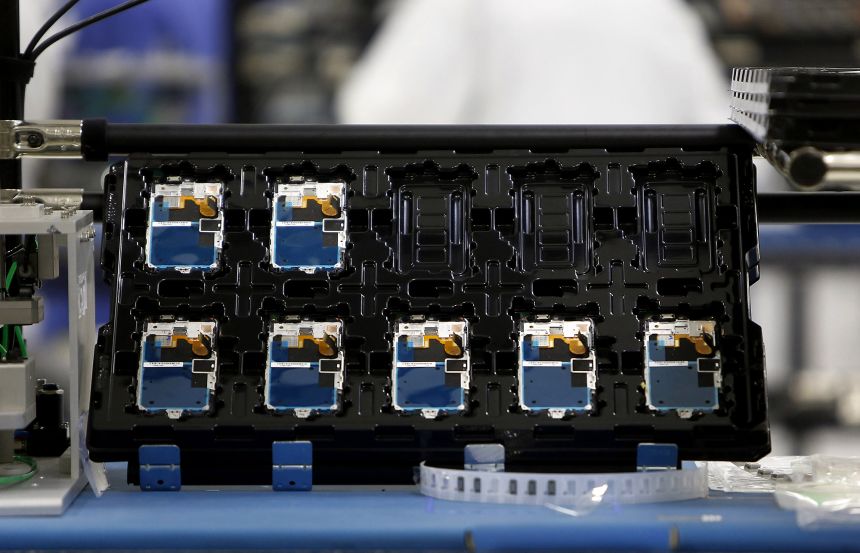

Even though Motorola assembled Moto X units sold in the US in Texas, components like the battery, screen and motherboard were sourced from suppliers in Asia, according to Woodside.

But the phone didn’t sell well enough to support efforts to assemble it stateside, with analysis firm Strategy Analytics reporting that only 500,000 had been sold in the third quarter of 2013, according to a Wall Street Journal report at the time. By May 2014, Motorola confirmed plans to shut the factory down and assemble the phone elsewhere.

“There definitely were higher costs, which was challenging,” Woodside said. “And you are dealing with a supply chain that’s very fragmented.”

Motorola’s efforts represent what may be the only attempt to build smartphones in America at scale. Tech startup Purism makes its Liberty phone in America, but it’s nowhere near the size of Motorola, which at the time was assembling roughly 100,000 phones per week from its Texas facility.

“It wasn’t like a science experiment; we had to be able to manufacture millions of phones in a year because that’s the market we were in,” Woodside said.

Among the biggest challenges Woodside encountered was training and retaining employees. Workers had plenty of other options, like jobs in retail or food service, making it difficult to attract and keep staff. Meanwhile, the specific nature of the work only made it more difficult.

“There’s probably several hundred (phone) parts, and they’re tiny,” Woodside said, comparing it to a “super tiny Lego set.”

“And what we didn’t appreciate is that most people were not accustomed to that kind of work at all in the US,” he said. “We had to train people on that specific type of work.”

Woodside’s experience touches on a reality those who follow trade and manufacturing know all too well: America is grappling with a skill and demand shortage that makes it difficult to fill factory jobs or onshore production of tech products like smartphones.

The US manufacturing sector lost an estimated 11,000 jobs between June and July according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s lower than the roughly 15,000 manufacturing positions that were eliminated between May and June, but it’s still one of the hardest-hit sectors in terms of job cuts for the past month.

While Trump’s whiplash tariff policies have made it challenging to create new factory jobs, there’s some evidence to suggest factories were struggling with finding the right people before then and that Americans simply may not want factory jobs.

A survey from the Cato Institute from August 2024 found that most Americans disagreed with the statement: “I would be better off if I worked in a factory instead of my current field of work.” Attracting and retaining a quality workforce was listed as a top business challenge facing US manufacturers in the National Association of Manufacturers outlook survey from the first quarter of this year.

The situation is different in China, where the labor market to assemble smartphones is plentiful and the manufacturing sector has been booming. In 2023, roughly 123 million people were employed in manufacturing in China, the most of any industry, according to the country’s fifth economic census published in December 2024.

China is home to Apple partner Foxconn’s sprawling Zhengzhou facility, where roughly 350 iPhones were assembled per minute even back in 2016, according to The New York Times. Apple has since shifted a portion of its manufacturing to India and Vietnam to reduce its reliance on China, making India the top exporter of phones to the United States for the first time.

Apple CEO Tim Cook described what makes China’s workforce ideal for smartphone manufacturing when speaking at a Fortune Magazine event in 2017, saying the country offers a combination of “craftsman” skills, “sophisticated robotics” and “the computer science world.”

Smartphone assembly, from what Woodside remembers, involved mounting small components like camera parts and chips onto a device – a task that he describes as requiring a lot of dexterity to do all day long.

“It was striking to me that we never thought about it,” he said.

China’s approach to developing the talent required to fill manufacturing jobs is different from the United States, where technical training and vocational education vary based on the state or the industry, according to Sujai Shivakumar, director and fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. That can make it difficult to grow a qualified workforce at scale.

Shivakumar told CNN that a workforce is as important as electricity and transportation infrastructure to a manufacturing strategy.

“And (China) anticipates that, and they build that into their planning,” he said.

Many new manufacturing jobs will likely require fresh skills — such as coding and data analytics — as artificial intelligence and automation play a bigger role in factories, Carolyn Lee, executive director of the Manufacturing Institute, previously told CNN.

Even so, Woodside cautions companies thinking about building electronics in the United States to carefully consider whether they’ll be able to find the right staff with the required skills.

“Understanding the nature of the product you’re making, and thinking about… ‘Are we going to have to completely train the workforce to understand this specific product?’ That’s something we didn’t quite anticipate,” he said.