AI’s drinking habit has been grossly overstated, according to a newly published report from Google, which claims that software advancements have cut Gemini’s water consumption per prompt to roughly five drops of water — substantially less than prior estimates.

Flaunting a comprehensive new test methodology, Google estimates [PDF] its Gemini apps consume 0.24 watt hours of electricity and 0.26 milliliters (ml) of water to generate the median-length text prompt.

Google points out that’s far less than the 45ml to 47.5ml of water that Mistral AI and researchers at UC Riverside have said are required to generate roughly a page’s worth of text using a medium-sized model, like Mistral Large 2 or GPT-3.

However, Google’s claims are misleading because they draw a false equivalence between onsite and total water consumption, according to Shaolei Ren, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at UC Riverside and one of the authors of the papers cited in the Google report.

To understand why, it’s important to know that datacenters consume water both on and off site.

The power-hungry facilities often employ cooling towers, which evaporate water that’s pumped into them. This process chills the air entering the facility, keeping the CPUs and GPUs within from overheating. Using water is more power-efficient than refrigerant. By Google’s own estimates, about 80 percent of all water removed from watersheds near its datacenters is consumed by evaporative cooling for those datacenters.

But water is also consumed in the process of generating the energy needed to keep all those servers humming along. Just like datacenters, gas, coal, and nuclear plants also employ cooling towers which – spoiler alert – also use a lot of water. Because of this, datacenters that don’t consume water directly can still have a major impact on the local watershed.

The issue, Ren emphasizes, isn’t that Google failed to consider off-site water consumption entirely. It’s that the search giant compared apples to oranges: Its new figure is onsite only, while the “discredited” figure included all water consumption.

“If you want to focus on the on-site water consumption, that’s fine, but if you do that, you also need to compare your on-site data with the prior works’ on-site data.”

Google didn’t do that. And it’s not like UC Riverside’s research didn’t include on-site estimates either. Google could have made an apples-to-apples comparison but chose not to, Ren contends.

“Their practice doesn’t follow the minimum standard we expect for any paper, let alone one from Google,” he said.

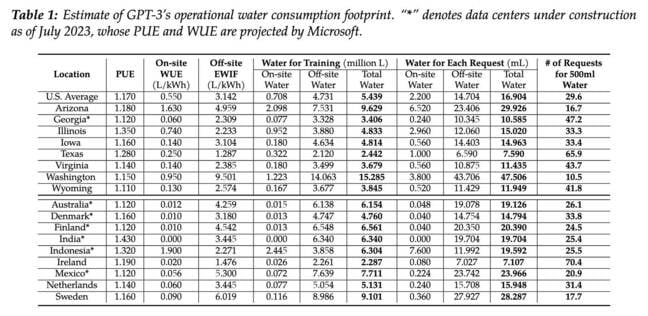

UC Riverside’s 2023 paper titled “Making AI Less ‘Thirsty’: Uncovering and Addressing the Secret Water Footprint of AI Models” estimated on-site water consumption of the average US datacenter at 2.2ml per request.

As you can see from the UC Riverside paper, on-site water consumption was far less than the 50ml per prompt cited in the Google report – Click to enlarge

The 47.5ml per request, which Google rounded up to 50ml in its paper, represented the highest total water consumption Ren’s team had recorded, and 2.8x higher than the US average.

“They not only picked the total, but they also picked our highest total among 18 locations,” Ren said.

Google didn’t address our questions regarding the comparison, instead providing a statement discrediting the UC Riverside researcher’s earlier findings as flawed.

“We have looked at the claims in the UC Riverside study, and our team of water resource engineers and hydrologists has concluded the claims and methods are flawed,” Ben Townsend, head of infrastructure strategy and sustainability at Google said in a statement. “The critical flaw in the generalized UC Riverside study is that it assumes a grid powered predominantly by traditional, water-cooled thermoelectric plants, which does not hold true for Google’s data center operations.”

Why Google proceeded to incorporate data on both on- and off-site water use from the UC Riverside paper, the search giant didn’t say.

While 0.26ml per prompt claimed by Google is still substantially lower than UC Riverside’s on-site average of 2.2ml for US datacenters, Ren emphasizes that those figures were first published in 2023.

If Google really has managed to cut Gemini’s energy footprint by 33x over the past year, that would imply the model was far less water-efficient at the time Ren’s team released their results as well.

The idea that AI workloads would become more efficient with time isn’t surprising, Ren notes. In the original paper, his team had predicted improvements in water and energy consumption. ®

Source link