Martian glaciers are mostly pure ice across the Red Planet, suggesting they might potentially be useful resources for any explorers that might land there one day, a new study finds.

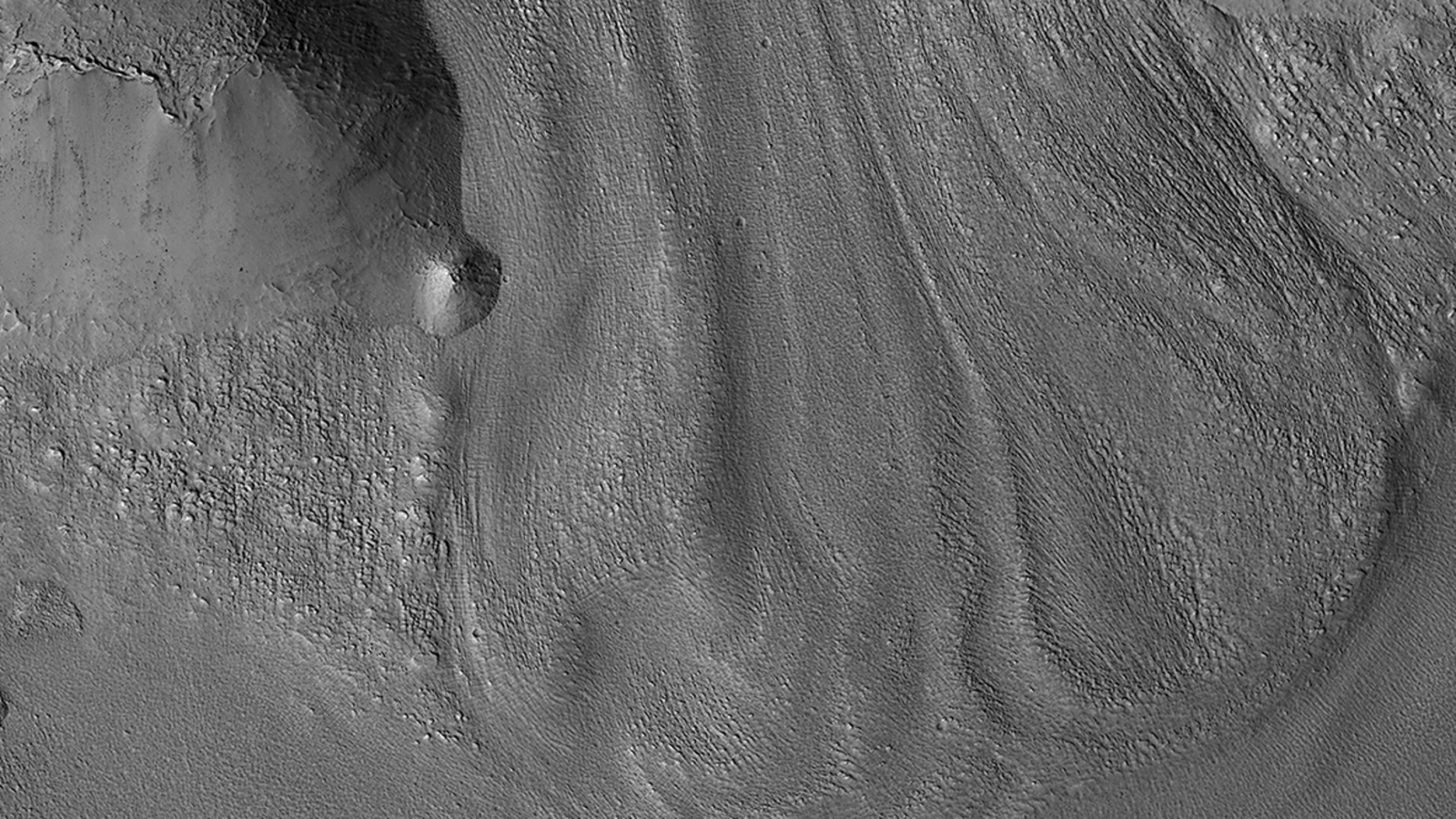

For decades, scientists have often seen glaciers coated in dust on the slopes of the mountains of Mars. Previous research suggested these were either glaciers that were comprised mostly of rock and as little as 30% ice, or debris-covered glaciers that were more than 80% ice.

“Different techniques had been applied by researchers to various sites, and the results could not be easily compared,” study co-author Isaac Smith, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona and an associate professor of Earth and space science at York University in Toronto, said in a statement.

To shed light on the composition of these glaciers, researchers used the shallow radar instrument (SHARAD) onboard NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter to analyze five sites on Mars. They focused on how quickly radar waves moved through a material and how quickly energy dissipated from radar waves into a material, which could shed light on the ratio of rock to ice within the glaciers.

“We found a surprising consistency in the purity of these glaciers,” study co-author Oded Aharonson, a professor of planetary science at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, and a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, told Space.com. “We found all the sites we looked at can be described as relatively pure ice deposits, maybe 80% or more ice, under a rock or dust cover. They could be a resource in the future if humanity tried to access them.”

The compositions of these glaciers were similar even in opposite hemispheres. That suggests the environmental conditions in which the ice was formed and preserved were likely consistent across the planet, according to the researchers.

“The ice may have formed through atmospheric precipitation — snowfall that led to glacial formation,” Aharonson said.

“Or it may have formed through direct condensation — glacial formation directly on the ground via the growth of frost,” he added. “It doesn’t seem like it would have formed through pore ice formation — when water vapor from the atmosphere diffuses to the subsurface and forms ground ice, which we know happens on Mars and terrestrial settings such as Alaska and Antarctica. If the ice in these glaciers had grown that way, we’d expect much higher levels of impurities, and that’s not what we see.”

The researchers next plan to analyze more glaciers on Mars to help solidify their understanding of this ice across the Red Planet.

The scientists detailed their findings online July 12 in the journal Icarus.

Source link