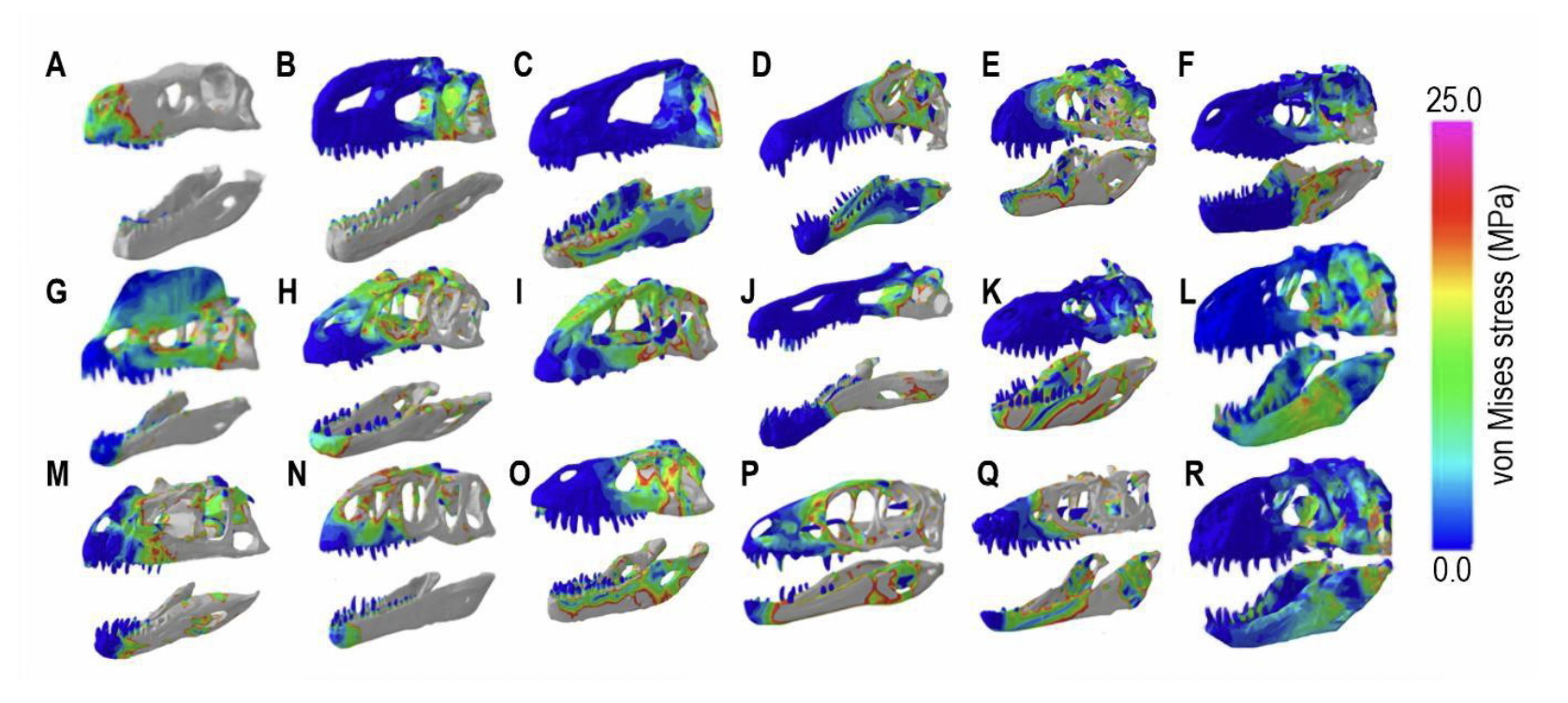

Analysis of 18 different carnivorous dinosaur species’ skulls has revealed that not all chompers chewed the same.

While Tyrannosaurus rex‘s skull is suited to the high-power crushing motion still favored by crocodiles, other predators of its ilk, like Allosaurus, had weaker jaws that would have slashed or torn the flesh of their prey, in a feeding style more similar to Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis).

The dinosaurs in this study were all theropods, a group of terrible lizards that boast the largest two-legged animals known to science.

Related: Dinosaur Skulls From Across The Globe Show How Ancient Continents Were Linked

With great size comes great appetite, and great jaws with which to satisfy it. Predatory dinosaurs like tyrannosauroids, megalosauroids, and allosauroids all reached gigantic proportions through evolution independently across time and space. The variations in their skull shapes suggest there are many ways to feed a giant, hungry dinosaur.

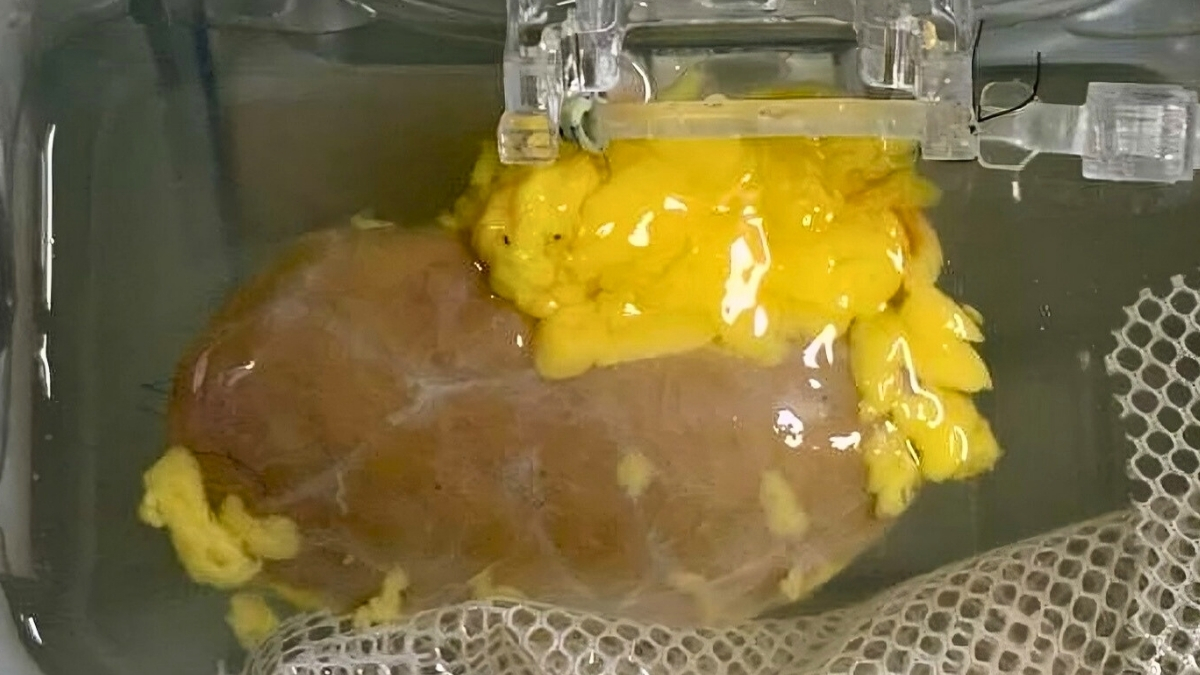

To explore these different strategies, paleobiologists Andre Rowe and Emily Rayfield from the University of Bristol scanned 18 dinosaur skulls to produce 3D models, and simulate each reptile’s bite. They were especially interested in how a dinosaur’s size related to the amount of stress exerted on its skull when biting down on prey.

“Tyrannosaurids like T. rex had skulls that were optimized for high bite forces at the cost of higher skull stress,” says Row.

“But in some other giants, like Giganotosaurus, we calculated stress patterns suggesting a relatively lighter bite. It drove home how evolution can produce multiple ‘solutions’ to life as a large, carnivorous biped.”

The relationship between overall size and skull stress, it seems, is more complicated. Some smaller theropods, like Raptorex, had the muscular machinery to deliver a much stronger and higher-stress bite than larger species, like Acrocanthosaurus.

“This biomechanical diversity suggests that dinosaur ecosystems supported a wider range of giant carnivore ecologies than we often assume, with less competition and more specialization,” Rowe says.

This research was published in Current Biology.

Source link