For decades, these aid programs received bipartisan support and made a difference. Cutting them will cost lives.

In total dollars spent, the United States was the world’s largest foreign aid donor in 2023. It gave $62 billion, about the same as the next three largest donors combined: Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom. The chart below shows the ten largest givers.

The US had a huge impact on the global budget, despite giving only a small share of its income. Of the ten countries that gave the most in raw figures, the US gave the smallest share of its national income: 0.24% of gross national income (GNI).

But because the US is so large, what America decides to contribute (or not) matters a lot.

Many Americans, and others, understandably wonder what impact this aid has had. Have their tax dollars made a difference?

Aid programs financed by American taxpayers saved approximately three million people every year

American foreign aid has contributed in many ways, from fostering economic growth and alleviating poverty in low-income countries to boosting food production and reducing malnutrition.1

But in this article, we’ll focus on one especially tangible way to measure the outcome of foreign aid: the number of lives it has saved.

We conclude that aid programs financed by American taxpayers saved approximately three million people annually. As we will see, it’s hard to estimate this precisely, so our “best estimate” of three million could plausibly be closer to two or four million.

This was a huge achievement that Americans can rightly be proud of. As we’ll see later, it comes at a comparatively low cost: Americans tend to vastly overestimate how much is spent on foreign aid, and support rises once they learn the real figures.

Note on America’s aid structure

Most of America’s foreign assistance for global health and humanitarian response came from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). USAID was the main American agency for delivering development assistance abroad.2

USAID alone had a budget of $43.8 billion, and made up around 61% of total US foreign assistance.3 The rest was channeled through other agencies, such as the Department of State. Most of the interventions covered in this article were funded through USAID.

The current US administration has dismantled USAID entirely and imposed deep cuts on many other foreign aid programs.

Estimating the number of lives saved by foreign aid is not straightforward. Health data from low-income countries is often limited, and we can never directly observe what would have happened without aid. In some cases, finances might come from elsewhere to fill the gap, but in others, it will go unfilled. That means all estimates come with considerable uncertainty, but they are precise enough to give us a sense of the impact.

The chart below is based on a recent analysis by Charles Kenny and Justin Sandefur of the Center for Global Development, in which they estimated the number of lives saved by American foreign aid.4

These figures are gross estimates. They reflect the number of lives that US foreign aid helped to save, rather than the exact number that would have been lost if the US had not provided this support. In some cases, other governments, charities, or communities might have stepped in to fill the gap.

Kenny and Sandefur focused on interventions targeting HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, vaccines, and humanitarian assistance. Their estimates range from 2.3 to 5.6 million lives saved annually, with their central estimate of 3.3 million. The breakdown is shown in the chart.

AIDS programs saved the largest number of lives: over 1.5 million per year. Between a quarter and half a million were saved by vaccines, tuberculosis, malaria, and humanitarian response each.

Note that there is possibly some overlap between a few of the categories. For example, one intervention to tackle tuberculosis is giving infants the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, which provides some protection against tuberculosis. So, there’s possibly some “double-counting” between the vaccines and tuberculosis categories. However, we would expect that these overlapping numbers are not large, and certainly not large enough to change the overall takeaway, which is that American foreign aid saved around three million lives per year.

Kenny and Sandefur’s estimates do not include lives saved from other aid programs, including improved access to clean water and sanitation, better nutrition, and family planning. We expect these to have saved lives, so the true figure might be higher.5

For these (and other) reasons, Kenny and Sandefur make it clear that these numbers are uncertain; their upper-bound estimates are more than twice their lower-bound ones.

Since this was just one analysis, it’s worth comparing these results to other estimates. A recent paper, published in The Lancet — which received a lot of attention — estimated that USAID averted 92 million deaths in the 21 years from 2001 to 2021.6 On average, that would be approximately 46 million per decade or 4 to 5 million lives saved annually.

Several experts have flagged methodological limitations in this study, so we would not recommend basing estimates from this paper alone. Still, it does give a similar figure of at least several million per year.7

PEPFAR has likely saved more than 20 million lives from AIDS

We can also compare the estimated deaths averted from specific diseases in these aggregate analyses to studies that look at HIV, tuberculosis, or malaria individually.

The US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief — better known as PEPFAR — is widely considered one of history’s most successful international aid initiatives.8

Launched in 2003, PEPFAR funds testing, antiretroviral therapy, prevention, and care in dozens of low- and middle-income countries, focusing on the hardest-hit regions of Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2023 alone, over 20 million people globally received antiretroviral therapy through PEPFAR.

In many of these countries, HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects women — especially young women. And without treatment, the virus can be passed from mother to child during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding. One of PEPFAR’s most transformative impacts has been interrupting this transmission chain for millions of mothers. Millions of babies who would have been born with HIV were instead born healthy. This means many of the lives saved by US aid were children’s.

So, how many lives has this program saved? The State Department administers PEPFAR and says the program has saved 25 million lives.9 But it’s also worth looking at independent analyses; a recent assessment finds that it has saved between 7.5 and 30 million lives.10 Again, this highlights how uncertain these estimates are but suggests that the State Department’s estimate of 25 million could be reasonable, as does Kenny and Sandefur’s estimate of around 1.6 million per year.

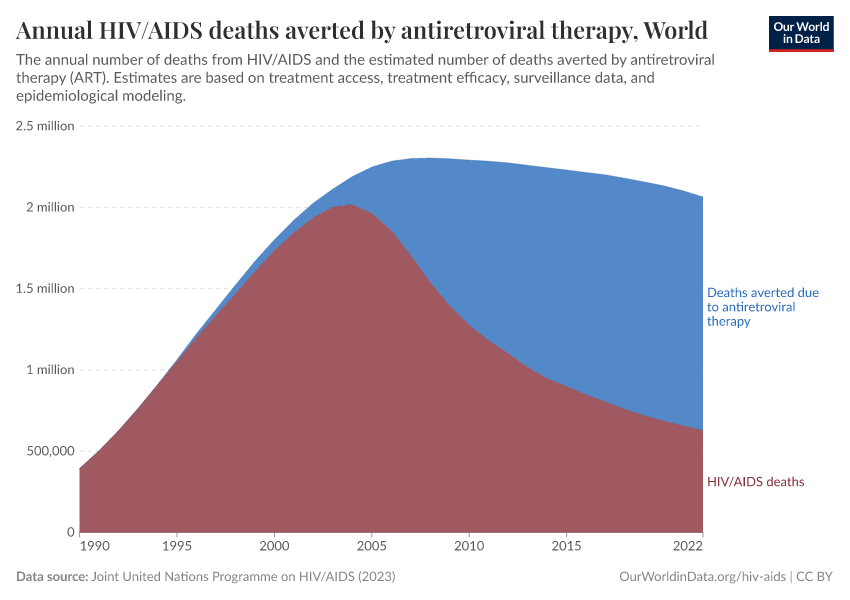

The chart below shows the estimated number of deaths from HIV/AIDS and the estimated number of deaths averted by antiretroviral therapy (ART) globally. PEPFAR wasn’t the only initiative expanding access to antiretroviral treatment, but was by far the largest. As the global rollout of ART gained momentum, HIV/AIDS deaths, which had been rising sharply, quickly plateaued — and then began a steep decline.

Republican President George W. Bush launched PEPFAR. Reflecting later on the moral imperative behind the decision, he wrote in his memoir Decision Points:

“I considered America a generous nation with a moral responsibility to do our part to help relieve poverty and despair.”

Through PEPFAR, Americans did just that.

American aid to tackle malaria has likely saved over 100,000 lives every year

In addition to its leadership in fighting HIV/AIDS, the US has played a vital role in the global effort against malaria through the President’s Malaria Initiative and contributions to The Global Fund.

Founded in 2005, this program supports malaria prevention and treatment in 27 African countries, the region hit hardest by the disease. It funds life-saving interventions: bednets, insecticide spraying, seasonal preventive medicine for children, and access to diagnostics and treatment. These efforts have contributed to large declines in malaria deaths in recent decades.

Kenny and Sandefur estimate that US foreign aid helped prevent around 293,000 malaria deaths yearly.11

This is a reasonable central estimate given the range within the literature. Studies provide higher and lower estimates, but these typically range from around 100,000 lives to 600,000 per year. In the footnote, we’ve included some more details of these studies.12

A figure of around 300,000 seems credible. Even if the true number were a few hundred thousand higher or lower, the conclusion would be the same: USAID has saved millions of lives yearly.

If American aid has saved several million lives each year, it would be reasonable to assume that taking that aid away will cost lives, possibly just as many if no other interventions or resources fill the gap.13

Programs that took decades to build are being ripped up in a matter of months

That hypothetical has become a reality this year, with the complete shutdown of USAID and cuts to other assistance programs. This has already had life-changing impacts on the people who would have received medicines, treatments, and humanitarian support. In countries like Uganda, clinics have already reported shortages of life-saving medication.14 Programs that took decades to build are being ripped up in a matter of months.

If we think that saving these lives in other parts of the world is fundamentally a good thing and worth protecting aid budgets for — not just in the US but in other rich countries, too — then public attitudes to foreign aid matter. Political representatives tend to pursue policies that are popular among the public.

Opposition to foreign aid, as a whole, is high across the American public. There is no disputing that. However, most Americans support giving aid for the life-saving interventions we looked at in this article. When people were asked what types of aid programs they think the US government should spend money on, the share supporting health programs was extremely high.15 83% of respondents said that the US should give foreign aid for “providing medicine and medical supplies to developing countries”.

However, Americans might still support aid cuts because they think the US spends too much. Indeed, recent survey data show that most Americans overestimate how much the US spends, often by a huge amount.

The US aid budget has been around 1% of total federal spending. But when KFF — a policy research and polling organization — asked people what share they thought was spent on aid, 30% believed that the US spent one-third or more of its budget on aid. And a staggering 15% thought that it spent more than half. That means they thought the US spent in a week what it actually gave for the entire year.

It’s worth noting that the survey design may have nudged respondents toward higher estimates, for example, by including several high-percentage response options, but none for 1% or less. Even so, the fact that more than half of the participants believed foreign aid accounts for over 10% of the federal budget points to a broader tendency to overestimate.

A 2016 Ipsos survey found a similar pattern: on average, Americans believed that more than 10% of the national budget — excluding military spending — went toward foreign aid.16

Perhaps most interesting (and encouraging) is that when respondents were told that the actual number was just 1% of spending, the share of people who said the US spent “too much” on aid dropped from 58% to 34%. Many Republicans, who are more skeptical of foreign assistance, also shifted to a more pro-aid position.

Most Americans vastly overestimate how much is spent on foreign aid, and support rises once they learn the real figures

It’s understandable: if you thought a third of the federal budget was being spent on foreign aid, you might be frustrated with the government’s priorities and the persistence of poverty and disease. But that is an inaccurate picture of how much is spent and whether it provides any benefit.

Not all aid is incredibly effective, but the very best aid is, and a small share of government budgets can save millions of lives.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Max Roser, Edouard Mathieu, Saloni Dattani, and Jack Ramm for their feedback and comments on this article and its visualizations.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Simon van Teutem and Hannah Ritchie (2025) - “Foreign aid from the United States saved millions of lives each year” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/us-foreign-aid-saved-millions' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-us-foreign-aid-saved-millions,

author = {Simon van Teutem and Hannah Ritchie},

title = {Foreign aid from the United States saved millions of lives each year},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/us-foreign-aid-saved-millions}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Source link