Four or five times a day, in a quiet suburb of Tallinn, Rasmus mixes a powder with water, carefully fills his syringe with it, and scours his body for a vein. The substance comes in various colours depending on the batch, and he often has to add ascorbic acid to the mix to make sure it combines well with the water and remains a stable solution, something he never had to do with fentanyl. But now he’s taking a new drug, and because of the various additives it’s often cut with, just a few hits could be enough to collapse a vein — making circulation to the area impossible. “In 2019 I could hit myself blindfolded,” Rasmus explains, speaking to UnHerd using a pseudonym. “Now it’s like a surgery.”

Now in his 30s, Rasmus is a high-functioning opioid addict. He has a steady income, dresses well, and speaks with authority. There is little about him that suggests he has been using hard drugs for more than half his life. But even as a preteen, Rasmus was never like the other kids his age. Fascinated by the physiological effects and molecular structures of various psychoactive compounds, he soon started experimenting with everything from marijuana to MDMA and amphetamines. By age 16, his exploration had driven him to severe anxiety and depression that left him feeling like a shell of his former self.

To cope, he turned to opioids — first to painkillers like tramadol, but eventually to fentanyl. “Before it’s like you’re naked, you’re in the middle of snow, you’re freezing,” Rasmus tells me in a commercial parking lot a stone’s throw from the deep blue waters of the Baltic Sea, recounting his first experience with the drug when he was around 19. “Then some mysterious stranger appears from the woods and invites you with him, and in about 50 meters a bright wooden cottage appears, you go inside, and he offers you a warm cup of tea. I felt like a human again.”

But those days are now little more than a distant memory. Fentanyl and its analogues have been largely absent from the Estonian market for years, after the country’s police cracked down on the Russia-connected organised criminal networks distributing them in 2017. Since then, the drug has been replaced by something even more sinister. In 2019, traces of a new class of synthetic opioids started showing up in Estonia’s drug supply. These can be tens of times more potent than fentanyl — and much more deadly. But it wasn’t until 2022 that these new designer drugs, called nitazenes, began to truly wreak havoc on Estonian society.

“Fentanyl is bad but nowhere near ’zenes in how addictive it is and how hard it grabs your opioid receptors,” Rasmus tells me, his eyes concealed behind dark glasses despite the shade. “It’s basically the crack of opioids.”

Nitazenes have wreaked havoc elsewhere. Deaths have been reported across the US, the EU, and the UK. In Britain alone, the drugs have been linked to the deaths of over 400 people between June 2023 and January this year, even as thousands more opioid deaths may have been been missed from official figures. Already, nitazenes are being hailed as the harbingers of the next European opioid crisis. In the midst of this gathering storm, Estonia stands out as its unexpected epicentre. Since they arrived on Europe’s doorstep, 96% of nitazene seizures have taken place in the Baltic states, and between 2022 and 2024, Estonia likely had the highest nitazene use rate on the continent. And while the rest of Europe was only just starting to take nitazenes seriously, by 2023, the drugs had already been implicated in 56 drug deaths in Estonia, comprising nearly half of all overdose deaths in the country, pushing it into the EU’s top spot for drug-induced mortalities per million people.

Estonia’s experience offers many lessons for the rest of Europe. But the story of nitazenes and opioids more broadly in Estonia is about far more than just law enforcement crackdowns, and underscores that the epidemic is ultimately not a problem created by the mere existence of a steady drug supply, but rather one borne out of a persistent socially-driven demand for the drugs. Woven into Estonia’s decades-long struggle with opioids, and hidden behind its reputation as a technologically advanced, highly developed Baltic economy, lies a history of unequal post-Soviet economic growth, the impact of social marginalisation, and the difficulties that state authorities and harm reduction workers alike have faced in combating a crisis that often dwarfs the resources their small country has at its disposal. Most worryingly, though, Estonia illustrates how once a robust base of addicts establishes itself within a society, not even rapid economic growth can uproot it — and that even if nitazenes can be eliminated, something worse will emerge soon enough to replace them.

“Somehow despite the fact that we had 17 years of experience with fentanyls, we still struggled with nitazenes,” says Katri Abel-Ollo, a researcher at the Estonian National Institute for Health Development who studies nitazene use patterns and overdose deaths. “So I can imagine that countries that don’t have experience with fentanyls, it could be quite shocking to them if nitazenes appear out of the blue.”

In 2002, Estonia became one of the first European countries to face a fentanyl crisis, after heroin smuggling routes were disrupted following the American invasion of Afghanistan. To compensate, local dealers, in cahoots with Russian gangsters, sourced fentanyls from nearby St Petersburg, exploiting connections between the Estonian criminal underground and the country’s former imperial rulers that had endured after the fall of the USSR. Soon enough, Tallinn became the “fentanyl capital” of Europe, leading to a 15-year battle that finally ended when Estonian police put the main players driving the drug trade behind bars, effectively shutting off the country’s fentanyl spigot.

“For five years we had a very good spell for a while,” Rait Pikaro, the head of the crime bureau of the Estonian Police North Prefecture tells me. “We were a bit naïve thinking that for five years… the market was, so to say, dead, but in that sense we were mistaken.”

Though fentanyl itself became much harder to find, Rasmus explains, fentanyl analogues continued to float around in the Estonian drug world, while harm reduction specialists I speak to suggest that users and dealers also turned to home-brewed opioid varieties to get by. When nitazenes emerged to fill the void, they arrived not from Russia, but from China, entering Estonia through Latvia. And in a sign of the changing drug landscape, this time there was no centralised dealer network, forcing police to play a game of cat-and-mouse with users and dealers across a fragmented market, both in Tallinn and across the eastern Estonian hinterland where opioids are most prevalent.

A far cry from fentanyl they may be, but nitazenes are ruthlessly effective, providing a powerful remedy for the withdrawal symptoms that are many addicts’ worst fear. “Potency does not equate to euphoria,” Rasmus tells me, recounting how nitazenes don’t even give him 1% of the same high he once got from fentanyl, despite how strong they can be. “Metonitazene [one of the earlier nitazenes to hit the Estonian market] for example was really good and pleasurable,” he says, “but some are just like you’re shooting up water.”

“Nitazenes are ruthlessly effective”

According to Abel-Ollo, nitazenes have a sharper come-up, but often a shorter duration — something that can be frustrating for users like Rasmus. “You inject it, it lasts maybe a minute, some last a few seconds, some last an hour, at best,” he says, describing some of the more recent nitazenes on the market. That was clear enough just looking at him: he was visibly more anxious during the latter part of our conversation as he felt his withdrawal symptoms set in, glancing around, breathing more shallowly, and becoming less focused in his answers.

To make matters worse for addicts, nitazenes are often so potent that they don’t respond like other opioids to naloxone, a medication that counteracts an opioid overdose, requiring several doses to work — something that contributes greatly to nitazenes’ lethality. For these and other reasons, Artur Kamnerov, a former investigator who heads the drug and organised crime bureau of the North Prefecture police department, predicts that if nitazenes become as prevalent elsewhere as they have in Estonia, countries can expect horrifyingly similar consequences. “If nitazene starts taking over the market,” he says with a resigned look in his eye and a heaviness in his voice, “there’s no stopping the overdose death rates.”

To explain what he means, on an unseasonably dreary and rainy summer morning, Kamnerov takes out his phone and opens up a Russian-language group on Telegram. Boasting 4,000 members, users can order Xanax, tramadol, and other painkillers. Another group has user-friendly menus where people could buy MDMA or amphetamines using cryptocurrencies. “This is the reason why no one really needs to go to the dark web anymore,” Kamnerov says. “It’s a hassle.”

Such ease of access is hardly limited to Estonia, of course. Narcotics, including nitazene class opioids, are sold this way to users and dealers alike in the UK and beyond. But what this means is that, at least in Estonia, easily accessible nitazenes shipped directly from overseas have bifurcated the opioid user base in the country, with two distinct cultures emerging. The older, more conservative community continues to rely on the more traditional street-based distribution networks, where a more hardcore culture of injection composed mainly of Russian-speakers reigns supreme. For their part, younger users source their drugs from online vendors and are predisposed to the less intimidating, more accessible pill forms of the drug.

For the moment, it is the former, Russian-speaking group that still dominates Estonia’s opioid landscape, and which has long formed the backbone of the country’s sky-high demand for these drugs. This community has its roots in the country’s decades-long occupation by the USSR, when Russian immigrants to the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic moved to Tallinn, Narva, and towns in Estonia’s northeast. These new settlers initially came to work in reconstruction after the Second World War, but additional waves later arrived when new housing projects like the Lasnamäe district were erected by Soviet authorities in Tallinn in the Seventies and Eighties. Russians were often given preferential treatment in housing allocation, crowding Estonians out of these much-coveted new apartments: once seen as beacons of Estonia’s bright socialist future.

Today, Russian speakers make up about 21% of Estonia’s population, but in stark contrast to their place at the top of the social hierarchy during the Soviet years, they emerged from the USSR’s collapse as an economically disadvantaged underclass. Great strides have been made to integrate Russian speakers into mainstream Estonian society, and Russian speakers now have access to the same social benefits as ethnic Estonians — but the baggage of years of socioeconomic hardship weighs the community down, and in many respects, their marginalisation persists. Russian speakers continue to make up 60% of prison inmates in the country, as well as nearly two thirds of homeless people in Tallinn. And with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Moscow has pummelled Russian speakers in Estonia with political disinformation: resonating with many, but further widening the gap with the Estonian majority.

That’s clear enough in Lasnamäe today. A world away from that long-dead communist ideal — let alone the charming and cosmopolitan centre of Tallinn — these suburbs are filled with monotone housing blocks, stretching out toward the horizon. The wide, sparse, avenues that separate them from each other give the area a liminal feel, a place that is neither in the past nor fully in the present. Their walls are adorned with Cyrillic graffiti: while many parts of Estonia have bilingual Estonian and Russian signs, here Russian predominates.

Fundamentally, Lasnamäe’s plight can be understood as a function of the end of communism. The collapse of the Soviet system brought with it major economic shocks, leading to a sharp decrease in Estonia’s GDP that affected everyone. In 1994, the country’s life expectancy dipped below that of Ukraine and Moldova.

By the following year, however, the economy started growing again, albeit unevenly, leaving many Russian speakers, most of whom voted against Estonia’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, stuck in the post-collapse era, reeling from their loss of status — not forever, but long enough for patterns of social stratification and self-sabotaging nihilism to burrow deep.

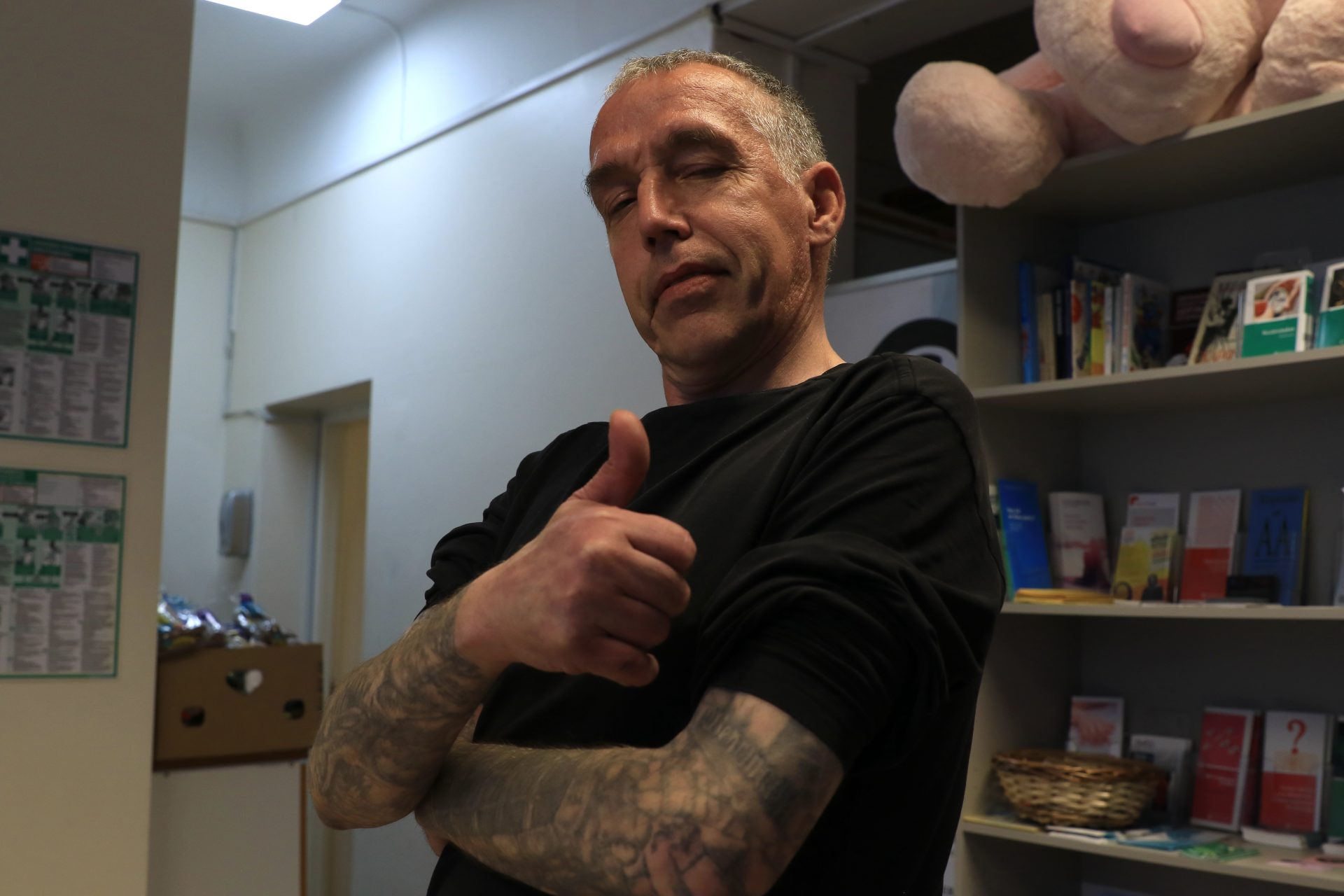

“That time, in the Nineties, was a time of gangsterism, very anxious times,” says Nikolai, a former addict and current harm reduction worker at MTÜ Convictus, an NGO working with drug users. Arms covered in tattoos and with a tired look in his eyes, he asks me not to use his last name: he has a long history with drugs and has spent time in prison. “When these drugs appeared, it was a coping strategy,” Nikolai explains. “It was better than drinking alcohol, and many Russian-speaking people followed this and started to use drugs. It was fashionable.”

Back in the fentanyl days, places like Lasnamäe, and Estonia’s Russian-speaking society in general, held the keys to the country’s opioid market. Rasmus, who is ethnically Estonian, learned Russian explicitly to purchase opioids from local dealers. “In the poorer regions of Tallinn, like Lasnamäe, Kopli, and so on, you could say that in every [housing project] there was a dealer,” he explains, adding that fentanyl was easy to get, but only if you spoke Russian.

Soon enough, even though he once told himself he would never shoot up, Rasmus was injected by a dealer not long after he got hooked on the drug. His first such experience was overwhelming, and he overdosed as soon as the fentanyl entered his body — but in doing so, he finalised his initiation into the hardcore, Russian-led Estonian drug culture that has driven the country’s opioid epidemic for so long.

Indeed, at MTÜ Convictus’s base in downtown Tallinn, while most of the clientele are still Russian speakers, more and more ethnic Estonians are showing up as well, pointing to the expanding reach of the crisis’s long tentacles. Regardless of linguistic or ethnic background, Convictus provides users with a place to exchange used needles for clean ones, get food, obtain naloxone, meet with social workers, or even just drink some warm tea. Yulia Rõbalko, another harm reduction worker at the centre, exchanges biscuits for used needles.

Harm reduction, she says, has two sides: one for the person, and one for the rest of society. “It works like a cycle,” Yulia Rõbalko. “You help him, he doesn’t spread disease with used needles, and so on. Normal people don’t see that.”

This blindness is part of the reason why harm reduction NGOs like MTÜ Convictus, which receive public funds from the Estonian state, are increasingly at risk of budget cuts, as peer-led services are being outsourced to organisations that don’t have as strong a connection to the community. If you ask Mart Kalvet, an activist with LUNEST, a drug policy group, building robust, grassroots support networks for drug users is only the first step in creating a long-term solution to the cycle of alienation, addiction, and suffering that has perpetuated the opioid crisis in Estonia for over a quarter century.

To secure real change within a context where a user base has already become entrenched, the state must implement a regulated, safe supply of drugs all while giving users access to the resources they need to live their lives as healthily as possible. That means not only providing sustainably funded rehab services, but also getting to the root of the problem and investing in places like Lasnamäe as real, evolving parts of country, rather than mere relics of its Soviet past. It also means treating the opioid epidemic like the public health problem it surely is, rather than an exclusively criminal one. “The harder you come down on the people who use drugs and sell drugs, the more problematic drugs appear on the street,” Kalvet says. “It’s an iron law.”

Already, Kalvet’s prophecy appears to be coming true. According to Abel-Ollo, there have been no new drug death cases in the country since May, indicating to her that there may be fewer nitazenes on the market. But if you ask Rasmus, who keeps a close eye on reports about drug arrests and court cases, even newer synthetic opioids, called brorphines, are already coming from China to replace them. Estonia’s game of whack-a-mole with opioids, it seems, will continue.

“This is where the somewhat dark-natured Scandinavian culture collides with the dark-natured, but in another way, Eastern Europe and Slavic culture,” Kalvet suggests, musing about the reasons for Estonia’s long dance with opioids. “We are affected by both, and not in a good way. It may be a cultural yearning for some warmth that our history has not provided us with.” From roaming Swedish armies in the 17th century, to Nazi and Soviet occupation in the 20th century, it’s easy to see what he means.

Yet whatever impact Estonia’s cultural proclivities may have on its drug appetite, the implications of its battle with nitazenes for larger and even more socially divided countries across the West are enormous. As markets in the UK, the US, Europe, and beyond continue to experiment with nitazenes as a more lucrative replacement for fentanyl and heroin, all signs suggest that long-time users will embrace these new drugs, creating a festering social wound that will persist so long as it has lives left to destroy. More ominously still, as Estonia’s case vividly illustrates, alienated segments of society — of which the West has plenty — can act as a fertile crucible for an opioid epidemic to not only take hold, but also spread. And in a world where thoughtful, nuanced drug policy reform is hardly on any government’s radar, the outlook is truly bleak.

After years of living at the mercy of his addiction, Rasmus tried to get help. On two occasions, he checked into the only long-term detox clinic in Tallinn that uses substitute therapy. But now, government funding cuts have quadrupled the cost of treatment there, leaving users like him with nowhere to turn. When I asked him how he sees his future in a follow-up conversation on Signal, his response was stark: “Most likely dead.”

Source link