Donald Trump has spent eight months attempting to remake the United States through a massive programme of cuts and deregulation. His administration has left almost no part of American life untouched – from classrooms to college campuses, offices to factory floors; museums, forests, oceans and even the stars.

An executive order signed last month to streamline rocket launches has been celebrated by officials in the commercial space sector, who see it as integral to securing America’s primacy as the world leader in space exploration.

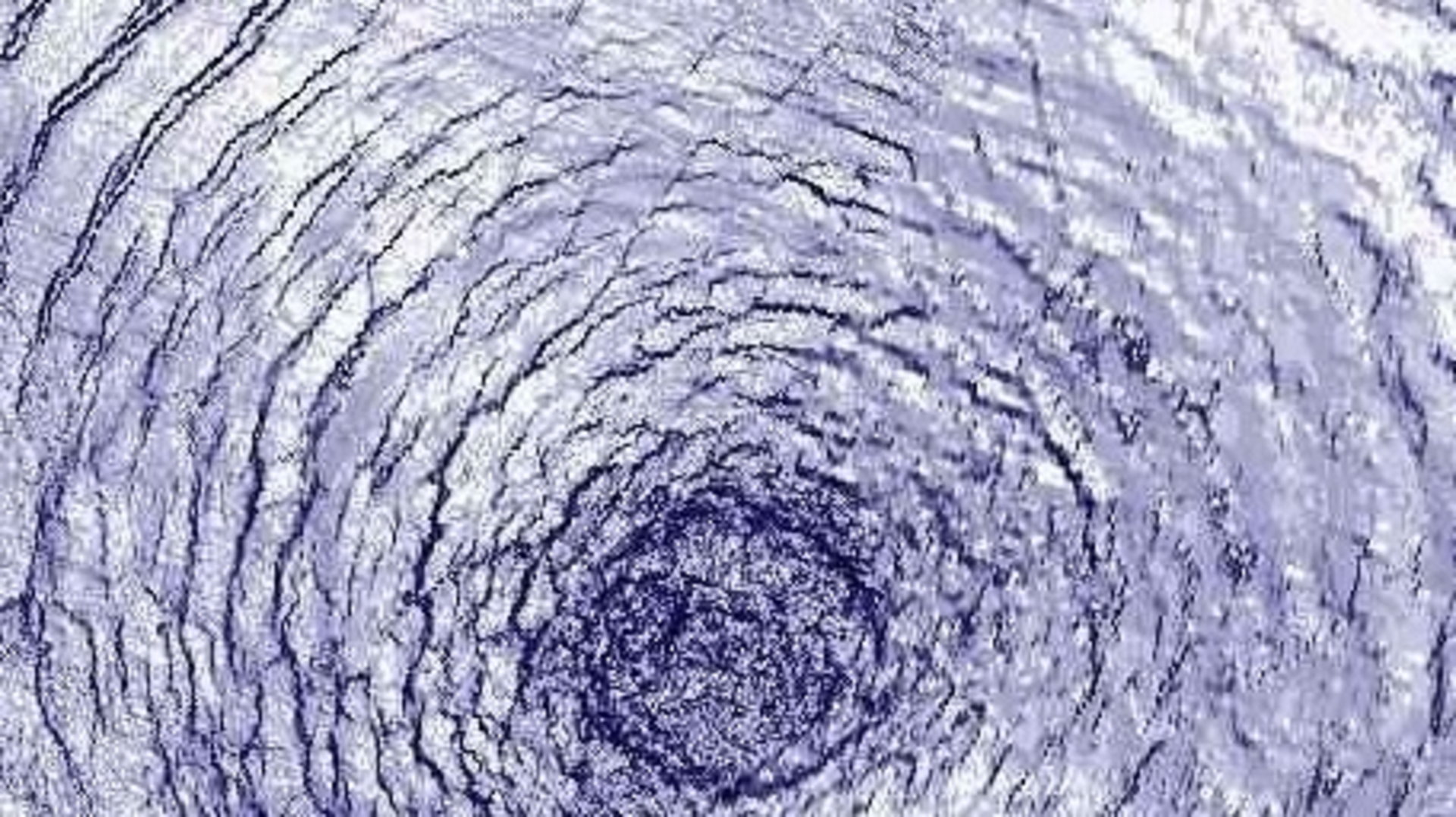

But it’s also causing a wave of alarm – from scientists, environmental activists and astronomers, who say a growing network of satellite constellations are crowding the skies, obscuring the stars and threatening our very access to Earth’s orbit.

From her her isolated farm in Saskatchewan, Samantha Lawler is just one of the many astronomers who has noticed the effect that satellites are having on her work. Lawler can see the Milky Way from her window, but the clear views afforded to her in Canada’s rural heartland are being overwhelmed by Elon Musk’s mission to bring internet to every corner of the Earth.

“It has changed how the sky looks,” says Lawler. “I look up and I’m like, ‘oh that constellation looks wrong.’ There’s a Starlink flying through it.”

Starlink is the network of satellites, operated by Musk’s SpaceX company, orbiting the Earth providing internet to those in remote, rugged and war-torn locales. But the venture’s lofty goal has come at a price for astronomers like Lawler, who have seen their work become more difficult as the sky fills up with satellites.

Starlink alone owns two-thirds of all satellites in space. With 8,000 in low Earth orbit, the company currently has permission to launch a further 4,000, and has reportedly filed paperwork to raise the total number to 42,000. Amazon and a state-backed project from China have their own rivals to Starlink in the works, all of which would see the numbers vastly multiply, with some estimates that in a decade there could be 100,000 satellites in orbit.

Trump has appeared to back the expansion of America’s commercial space industry, signing an executive order last month that could accelerate the number of rockets and their massive payloads of new satellites, potentially exacerbating the difficulties for astronomers and bringing unintended environmental damage.

The fight for space

Commercial space operations have grown in scale and ambition since the US stepped back from government backed flights and increasingly turned to private companies like SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin. In recent years, government efforts to regulate the industry have struggled to keep pace with the ambition of these companies operations: in the last four years, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has issued more commercial space licenses than it did in the entire 32 years before 2021.

At various points, the companies themselves have expressed frustration with the government’s regulatory regime – Elon Musk himself threatened to sue the FAA last year for “overreach”.

Trump’s August executive order would seeks to eliminate some environmental reviews and launch safety measures contained in previous regulations produced by the president’s first administration, while also preempting some state laws that could hinder the development of private space ports.

The FAA itself predicts that the number of commercial launches could almost quadruple over the next decade. With up to 28 satellites launched from a single rocket, the accelerated launch timetable enabled by Trump’s slashing of red tape will be essential if companies like SpaceX are to expand their satellite constellations.

The cataclysmic danger of ‘space junk’

“What are the skies going to look like?” In a career spent contemplating big questions, it’s perhaps this which is the most existential for Lawler.

Her research looks at small icy objects at the edge of our solar system known as Kuiper belt objects. Understanding them could help us form a picture of how the solar system formed and the planets aligned. It’s work that could fundamentally shift our understanding of the very universe we inhabit.

“I would love to know what else is out there … what’s beyond the edge of what we know,” says Lawler. “There might be another planet in our solar system. But for the first time it’s getting harder to do the work because of the actions of for-profit companies.”

She says that when she points her telescope at the sky her field of view is often obscured by bright streaks of satellites.

“The way the satellite streaks appear on the sky, in different seasons and different times of night, it’s actually made it harder to look in one particular direction than in other directions,” says Lawler.

It’s a common complaint from astronomers, who also say that the burning up in the Earth’s atmosphere of satellites that have reached the end of their lives could create untold damage.

“All that metal, plastic, computer parts, solar panels, that just gets deposited in the atmosphere,” she says, with studies suggesting this could cause ozone depletion and change the opacity of the atmosphere.

“We’re just running this experiment and that is really terrifying.”

The proliferation of “space junk” in orbit is also of concern to experts. There are about 43,000 objects being monitored in space, most of which are debris from old rockets and disused satellites. The European Space Agency estimates that there are an addition 1.2 million tiny objects between 1cm and 10cm wide.

The risk of a runaway collision of debris – a phenomenon known as Kessler Syndrome – is thought to be increasing as the number of satellites multiplies. In such a scenario, one collision sets off a chain reaction which would see more debris produced, until a critical mass of cascading collisions renders orbit inaccessible.

Global communications company Viasat paints a cataclysmic picture of the world after such an event: “All of humanity would watch helplessly as space junk multiplies uncontrollably. Without timely intervention, we risk bringing the Space Age to an inglorious end, and trapping humanity on Earth under a layer of its own trash for centuries, or even millennia.”

“That’s one of the most ironic things, there’s all this talk that we need to go to Mars, we need to colonise another planet, but all these satellites in orbit actually make it much more likely that there’s going to be a catastrophic collision,” says Lawler.

Companies like Starlink are acting to mitigate such an event by building in avoidance systems that manoeuvre their satellites around potential collisions, while scrapping older models that are more at risk.

“So far it’s been perfect,” Lawler says.

The real risk, she says, will come when the thousands of Starlinks competitor satellites are in orbit in a few years time, with question over how they will coordinate and share data so that other operators know they’re there.

“Right now one American private company effectively controls orbit,” says Lawler. “If you want to go to a higher altitude orbit, you have to talk to Starlink and make sure that they’re not going to hit your satellite as you go through.”

The Guardian has approached SpaceX and the White House for comment.

Despite some astronomers calling for a moratorium on rocket launches, Starlink and its celestial competitors show no sign of pausing their ambitions.

Starlink appears to be aware of the effects it satellites have of the work of astronomers and has made efforts to make them fainter in the sky. But Lawler says at the same time, the objects have become bigger, “so it just cancels out.”

“It’s an engineering challenge that satellite operators need to think more about: How do you deliver your services with fewer satellites? How do you make your satellites last longer?”

Despite the cost to her work, she concedes that the service offered by Starlink and its soon-to-be competitors is an engineering miracle. But she believes that the potential downsides outweigh the convenience that they provide.

Lawler says it may take a serious collision in orbit to focus the minds of politicians and policymakers to the danger of deregulated commercial space operations, likening such a scenario to a cataclysmic news event like the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill.

“I really am afraid that something very bad has to happen before things will change.”

Source link