Over a century of progress in surgery, drugs, prevention, and emergency response has driven down death rates from heart disease and stroke.

For much of history, heart disease was a mystery. Middle-aged adults often collapsed without warning, and doctors usually blamed “dropsy”, “apoplexy”, or simply “old age.”1

In 1945 — at just 63 years old — President Franklin D. Roosevelt was sitting for a portrait when he raised a hand to his head and whispered, “I have a terrific pain in the back of my head.” Minutes later, he lost consciousness and died from a massive brain hemorrhage — a consequence of uncontrolled high blood pressure and heart disease, which doctors at the time couldn’t treat.2

Roosevelt wasn’t alone. Mid-twentieth-century medicine, even for some of the world’s most powerful people, often lacked the tools to treat or sometimes even diagnose specific cardiovascular diseases.

There was no routine blood pressure screening. There were only basic diagnostic tools — no CT, MRI, or echocardiography to spot clots or artery damage. Even if someone was diagnosed, few effective medicines or surgeries were available to treat them.3

Today, pills could have driven down Roosevelt’s blood pressure within weeks. The hypertension that struck him and many others without warning, often known as “the silent killer”, is routinely diagnosed and treated.

Cardiovascular diseases — the broad term for conditions that affect the heart and blood vessels — are still the leading cause of death worldwide. But the story reflects a remarkable and often overlooked fact: the risk of dying from cardiovascular diseases has fallen dramatically in recent decades.

In the United States alone, the age-standardized death rate from cardiovascular disease has fallen by three-quarters since 1950. This means that for people of the same age, the annual risk of dying from cardiovascular disease is now just one-quarter what it was in 1950.

This progress was built on decades of biomedical research, surgical advances, public health efforts, and lifestyle changes, which means that far fewer people die from sudden strokes or heart attacks. If they do, it happens much later, after they’ve lived longer and healthier lives.

In this article, I’ll look at how and why deaths from cardiovascular disease have declined. I’ll focus on data from the United States, but as we’ll see, many other countries have followed a similar path.

The annual risk of dying from cardiovascular disease has fallen dramatically.

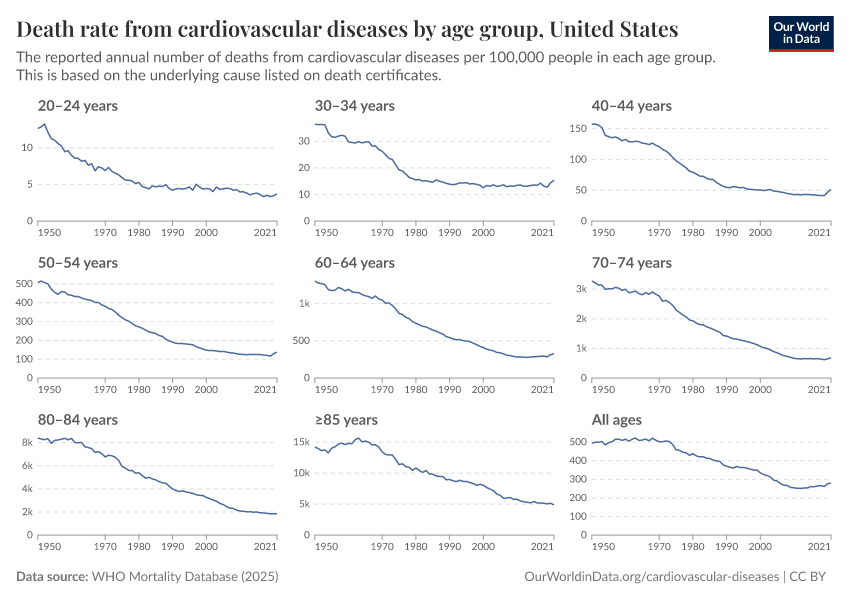

In the chart below, you can see this decline across age groups. Across all ages, the risk of death from cardiovascular disease has fallen.

Note that the vertical scales vary between age groups; the risks are much higher at older ages.

For example, women over 85 are about two-thirds less likely to die from cardiovascular disease today than women over 85 in 1950. This pattern is visible for both men and women, from young adulthood through old age.

These rates can be combined into the age-standardized death rate from cardiovascular disease. This lets us understand how the risk has changed for people of the same age.

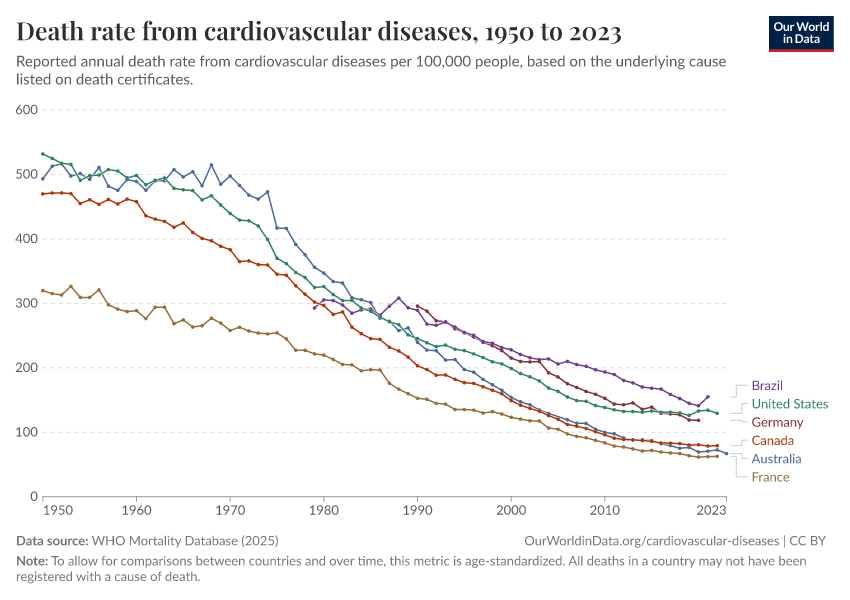

It’s shown in the chart below. In the United States, that risk has fallen dramatically. In the 1950s, over 500 out of every 100,000 people died of cardiovascular disease each year. Today, that figure is below 150 — a decline of around three-quarters.

This metric also lets us see if this improvement is unique to the United States or has happened elsewhere. As you can see, there have also been large declines in many other countries, including Australia, France, Canada, Germany, and Brazil.

These gains haven’t simply shifted health risks to other causes. Instead, the drop in cardiovascular mortality is a major reason why overall death rates have fallen and life expectancy has risen globally. Fewer people dying early from heart attacks and strokes means many more years lived in better health.

What made this progress possible?

There wasn’t just one discovery or intervention that did it all. Medical breakthroughs — in detection, treatment, surgery, and emergency care — have made surviving cardiovascular disease much more likely. In addition, public health measures and lifestyle changes have stopped many people from developing it in the first place.

The twentieth century was a very exciting time to be a cardiovascular doctor or surgeon. Many breakthroughs have made surviving cardiovascular disease far more likely. I’ve shown many of them in the chart below, and will go through some of them in more detail.

Drugs to prevent and treat heart disease

One major area of progress has been the development of drugs that can help people manage risks and treat heart conditions when they appear. This includes:

- Statins, which were first used widely in the 1980s, help millions keep their arteries cleaner by lowering LDL (“bad”) cholesterol levels and stabilizing plaque that can clog blood vessels.4 Newer drugs, like PCSK9 inhibitors introduced in 2015, help people lower LDL cholesterol when statins aren’t enough.5

- Blood pressure medications, like beta blockers, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and diuretics, help keep high blood pressure under control, reducing the risk of strokes, heart attacks, and heart failure.6

- Clot-busting medicines are used to break up blockages and quickly restore blood flow, and dramatically improve survival rates for heart attack and stroke patients.7

Treatments like these are routine today and have substantially lowered the chances that people with high cholesterol, hypertension, or previous heart problems will go on to develop life-threatening complications.

Devices, diagnostics, and surgeries

Beyond drugs, medical devices and surgical techniques have revolutionized cardiovascular care. Just over a century ago, the heart was considered untouchable. Surgeons feared, often rightly at the time, that opening the chest would lead to massive bleeding or deadly infections.

Heart surgery became possible through advances in anesthesia, antiseptics, blood transfusions, positive pressure ventilation, and the invention of the heart-lung machine. This opened the door to an organ that was previously seen as untouchable.

Here are some other key advances over the past century:

- Stabilising the heart’s rhythm. In the late 1950s, doctors implanted the first pacemaker, which sends tiny electrical signals to keep the heart beating at a healthy rhythm when it slows down too much.8 By the 1980s, implantable defibrillators were added to detect dangerous heart rhythms and deliver a shock to restore a normal heartbeat — helping prevent sudden death in people at high risk.9

- Looking inside the heart. Doctors first used echocardiography in the early 1950s to watch the heart’s real-time movement.10 CT scans in the 1970s and MRIs in the 1980s brought clearer views of blockages and damage, without the need for surgery.11

- Treating blocked arteries has transformed as well. In 1974, doctors first used angioplasty to thread a balloon into clogged arteries and restore blood flow. Doctors soon applied this to the coronary arteries, opening them up without needing open-heart surgery.12 Stents — tiny mesh tubes that keep arteries open — followed in the 1980s, and in the 2000s, drug-coated versions (“drug-eluted stents”) were introduced to prevent re-narrowing.13

- Bypassing severe blockages. When stents weren’t enough, surgeons could reroute blood around the blockage using a healthy vessel from another part of the body. This bypass surgery became a routine and life-saving option by the late 1960s.14

- Repairing and replacing heart valves. In 1960, the first mechanical heart valve was implanted.15 Later, in the 2000s, transcatheter valve replacement allowed damaged valves to be replaced through a thin tube instead of open surgery, offering a safer alternative for many patients.16

- Replacing the whole heart. For people with severe heart failure, the only solution might be a transplant. The first successful human heart transplant took place in 1967.17

- Precision through robotics. Robotic assistance in surgery began in 1985, and precision was improved with tools like robotic arms or biopsy needles. Over time, more devices were added, and eventually they were combined in the first “da Vinci” surgical robot, which let surgeons perform complex operations through a small incision, with precise wrist-like instruments, all controlled from a console displaying a 3D view.18

Emergency care

Saving lives from heart attacks and strokes hasn’t depended only on hospitals and doctors, but also on what happens in the first critical minutes.

In the 1930s, London introduced the world’s first “999” emergency phone line, allowing anyone to call for help quickly. The United States followed decades later, with the first “911” call in the 1960s.19 As emergency phone systems expanded, emergency care and ambulances became more widely used. Alongside them, new tools and techniques were developed that allowed both professionals and bystanders to act quickly.

One of the most important came in the 1950s, when cardiologist Paul Zoll developed the first external defibrillator. This device could deliver an electric shock to restart a stopped heart. This technology became portable, safer, and easier to use in the following years. Eventually, automated external defibrillators (AEDs) were designed so ordinary people could follow voice instructions, apply pads, and deliver the life-saving shock within minutes, even before emergency services arrived.20

Around the same time, researchers developed cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), another tool that would become central to emergency care. By the late 1950s, CPR — a combination of chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth breathing — gave bystanders a way to keep blood and oxygen temporarily flowing until emergency care arrives.

As these interventions became available, getting the wider public to recognize emergency signs became more valuable so they could respond quickly and effectively. Many large public awareness campaigns were launched. The American Heart Association led efforts in the US to teach people how to recognize heart attack symptoms — like chest pain, pressure, or pain in the arm — and to seek help immediately.21 More recently, the UK’s “Act FAST” campaign helped people spot strokes by remembering four key signs: “Face drooping, Arm weakness, Speech trouble, and Time to call 999.”22

Together, these developments have prevented many heart attacks and strokes from becoming fatal. Many more people get treated within minutes, not hours, and that speed has saved many lives.23

Public health efforts and lifestyle changes have reduced cardiovascular risks

In the chart below, I’ve compiled some of the biggest risk factors of cardiovascular disease — obesity, uncontrolled blood pressure, cholesterol, and cigarette smoking. Data on all four risk factors has been available from national surveys since 1999, so the chart focuses on the most recent decades.

You can see that, over decades, obesity has worsened, but the other risk factors (uncontrolled blood pressure, cigarette smoking, and high cholesterol) have improved. Public policy opened the door, but millions also changed their daily habits. This led to a change in the risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

One important reason for progress is the decline in smoking, thanks to tobacco control efforts. Cigarettes carry a mixture of carcinogens and harmful chemicals that injure blood vessels and fuel inflammation, which means fewer people smoking leads to fewer people developing clogged arteries and heart disease. In the 1960s, about 40% of US adults smoked cigarettes. Today, it’s less than 15%.24

Another improvement has been with cholesterol. High levels of LDL cholesterol — sometimes called “bad cholesterol” — contribute to fatty deposits in arteries, raising the risk of heart attacks and strokes. Average cholesterol levels have fallen since the 2000s. This is likely the result of factors such as national screening programs to detect high cholesterol levels early,25 dietary guidelines that encouraged cutting trans and saturated fats26, and due to a wider use of statins — drugs that lower cholesterol levels and help prevent dangerous buildups in arteries; they are one of the most prescribed drug classes today and play a key role in preventing heart attacks and strokes.27

Uncontrolled high blood pressure is another major risk factor. High blood pressure can develop when blood vessels become stiffer or narrower — but it can also drive further damage by putting extra pressure on artery walls, making them more likely to weaken, clog, or rupture, leading to strokes, heart attacks, and heart failure.28 The share of adults with high blood pressure has fallen since the late 1990s, likely due to better detection, better medication, and more routine monitoring.

Unfortunately, not all trends have been positive. Obesity has increased steadily and remains a major risk factor for heart disease — partly by raising blood pressure and cholesterol (which treatments have helped control), but also through other pathways like insulin resistance, inflammation, and extra strain on the heart. New treatments and weight loss medicines could help reverse this trend, but they’d need to be used widely to make a difference.29

Another factor often missed is vaccination for infections like influenza and pneumococcal disease, which have also helped protect people from these infections that can trigger heart attacks.30

Looking back, it’s surprising to realize how many lifesaving tools we have today that didn’t exist until quite recently in history. Antiseptics to prevent infections, CPR to restart the heart, pacemakers to keep it beating, simple blood pressure cuffs to warn of hypertension: these tools are each so common we now rarely think about them or what life was like before them.

The dramatic decline in cardiovascular deaths shows just how much can change with science, policy, and everyday habits.

Heart disease is still the leading cause of death worldwide, killing around 20 million people globally each year, and this tells us there’s still more to do. And some risks, like obesity and diabetes, have risen in many countries. They remind us that progress can stall or even reverse without more effort.

But new advances are pushing the boundaries of what’s possible even further. 3D heart reconstructions help surgeons plan complex operations more precisely; new valve replacement techniques mean patients can recover faster without surgery; and newly developed weight loss drugs offer hope for tackling obesity across the population.

The fight against cardiovascular disease isn’t over. Understanding what brought us this far, and seeing continued progress today, tells us that even more is possible. The next chapters in this story are up to us.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Saloni Dattani (2025) - “Death rates from cardiovascular disease have fallen dramatically — what were the breakthroughs behind this?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/cardiovascular-deaths-decline' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-cardiovascular-deaths-decline,

author = {Saloni Dattani},

title = {Death rates from cardiovascular disease have fallen dramatically — what were the breakthroughs behind this?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/cardiovascular-deaths-decline}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Source link