Gloria García was born in Mexico 42 years ago, but for two decades she had been building a life for herself and her family in California and was one step away from obtaining legal permanent residency in the United States. Now, she says, she’s suffering a painful separation from her family, trapped in administrative limbo in Tijuana, even though, she stresses, she has followed all the rules to apply.

In 2019, García began the process to obtain a family-based green card, which was supposed to have ended in March with an interview at the U.S. Consulate in Ciudad Juárez. But State Department authorities later notified her that they were returning her case to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, claiming they needed to review a document that, according to her lawyer, had already been approved by them.

“They wanted to make sure everything was in order, but I find it very curious since they already did so in the final step,” said her lawyer, Fernando Romo. The U.S. Embassy in Mexico City declined to comment. USCIS hasn’t responded to another inquiry.

“We’re seeing a different attitude in the consulates, a stricter attitude, looking for any detail to deny or question the process,” Romo said.

Immigration attorneys consulted by Noticias Telemundo and not connected to Garcia’s case said that wait times have become longer and that interviews at consulates have become more difficult this year.

Meanwhile, these days there’s “a lot of crying, a lot of anxiety, waiting for them to tell us that everything will be OK,” García told Noticias Telemundo via video call from Tijuana, 105 miles from Santa Ana, California, where her family lives and whom she hasn’t seen for six months.

García is married to Tomás Ortega, 47, and is the mother of Alyssa, 21; Tomás, 18; and Isabella, almost 3. She’s the only one in her family who isn’t a U.S. citizen, but she believed she was on the verge of finally achieving that status.

García emigrated from Zacatecas, in central Mexico, to California in 2003, at age 19. From the United States, she hired a lawyer to process her divorce in Mexico, because, she says, she had to flee a violent relationship with her now ex-husband.

But there was an administrative error in her divorce ruling that her attorney resolved years later when she sought to begin the green card process. In August 2019, the Orange County Superior Court upheld the correction, according to a court document obtained by Noticias Telemundo.

García started her green card process with an I-130 petition, which allows a U.S. citizen — in this case, Ortega, her husband — to petition for a relative to become a legal permanent resident. The next step was a temporary waiver application, which was granted.

All she had left was an appointment at the consulate in Mexico. But during the interview, the agent asked to review the divorce paperwork.

“They’re supposed to check that everything is in order and make a determination based on the information already submitted,” said Romo, her attorney. USCIS had already approved the divorce document, so “by the time I got to the interview, it should have been a five- to 10-day process,” he said. He added he was “confident” that “immigration will rectify” and approve García’s case.

However, it has been six months without any news, and there’s no certainty it won’t be much longer, Romo said.

“It’s incredibly frustrating for us,” he said. “We can’t imagine how she feels, but that’s the system we live in, and it’s the system we were dealt.”

According to USCIS, as of July, 2.4 million applications for family-based residency were pending; 80% had been on hold for more than six months.

After she learned of the consulate’s decision, García traveled from Ciudad Juárez to Tijuana to be closer to her family in California. Unable to return to the United States, the family decided to have their youngest daughter, Isabella, stay with García for her to care for because the girl has ptosis, an eye condition that prevents her from focusing, and they also lack the resources to pay for day care.

The mother and daughter live in a modest room for which they pay monthly rent in a working-class neighborhood of Tijuana as they wait for news.

Kathia Quiros and José Gutiérrez, immigration attorneys who aren’t involved in García’s case, said they’ve also seen that the State Department has tightened consular processes in the current Trump administration. “Scrutiny is greater in some cases — there are some immigration officers who are reviewing everything the USCIS office does and are finding new reasons to deny cases,” Quiros said.

“We’re noticing that immigration authorities are looking for other, sometimes practically insignificant, technical reasons to force the person to correct the problem, and that makes the process take longer,” Gutiérrez said. “People are being forced, at best, to spend months abroad.”

In July, García’s husband and two other children crossed from California to Tijuana to celebrate Alyssa’s 21st birthday. They shared a meal of wings and spent a few hours together, an experience García treasures in a short video in which they are seen smiling.

“It’s very difficult to leave my children. Even though they’re adults, we’ve always been together. I have my daughter with me, but her dad leaves, she’s crying, she wakes up in the middle of the night crying, looking for him,” she said.

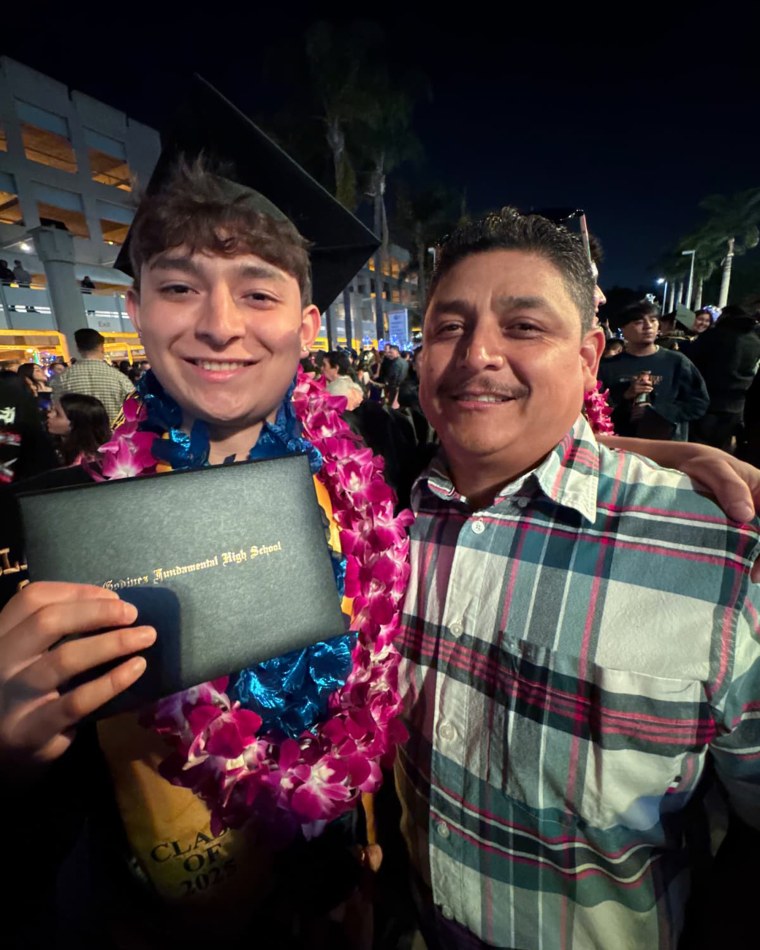

The phone has been her only ally: It was through a video call that she watched Tomás’ high school graduation.

Ortega said: “The family is a team; the team has to be together. The distance affects us, emotionally and financially.”

“A part of us stays there,” he said. “It’s difficult because you have to live, pay bills here and there. Wherever you are, you have to keep paying.”

García’s daughter Alyssa said they’ve always depended on their mother, “not so much physically but emotionally. … Sometimes I can’t go through my day without thinking about the fact that we’re in this situation.”

García asks only that immigration authorities review her case as soon as possible so she can “do the right thing” and return to her family. “That’s what the president wants, for us to do things right. We’re doing the best we can,” she said.

Alyssa hasn’t lost hope and acknowledges that her mother “has had to bear the brunt” of the separation.

“Half of me is proud that they’re fighting these issues that we have and that my mom is fighting honestly and correctly,” she said. “I’m very proud of her.”

An earlier version of this article was first published in Noticias Telemundo.

Source link