Children with a restrictive eating disorder show recognizable changes in brain structure, according to a new study.

Identifying the causes of these changes could help researchers understand how these conditions relate to other neurodevelopmental disorders and how they might be better treated.

Magnetic resonance imaging scans of 174 children aged under 13 who had been diagnosed with an early-onset restrictive eating disorder (rEO-ED) were analyzed by an international group of researchers, and compared with scans from 116 children without a diagnosis.

The motivations behind the study were to look for differences between disorder types, and to see if there were any relationships with brain structures associated with neurological conditions such as obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

Related: Anorexia Patients Reveal a Distinct Pattern in Their Brain Activity

“Early-onset restrictive eating disorders encompass a heterogeneous group of conditions, including early-onset anorexia nervosa and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorders (ARFID),” write the researchers in their published paper.

“However, the impact of rEO-ED on brain morphometry remains largely unknown.”

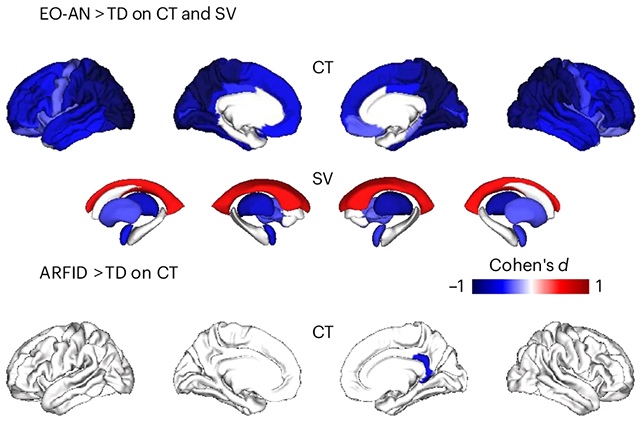

The researchers spotted some differences in brain structure for both early-onset anorexia nervosa (including a thinner cortex and more cerebrospinal fluid) and for underweight patients with ARFID (including a reduced surface area and reduced overall brain volume).

As this study is limited to a snapshot in time, it’s difficult to confirm whether structural brain variations are a cause or a consequence of these disorders.

Among the children with early-onset anorexia nervosa, changes to cortical thickness were more closely linked to body mass index (BMI), suggesting the differences in neurology may be a consequence of restrictive eating behaviors.

To trace any overlap between restrictive eating disorders and other neurodevelopmental conditions, scans were obtained from a variety of external datasets. The team found similarities in in cortical thickness signatures between early-onset anorexia nervosa and OCD, and between ARFID and autism.

Somewhat surprisingly given previous research, there was little overlap between anorexia nervosa and autism, or between ARFID and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“Overall, this multiscale overlap – at the clinical, brain and genetic levels – suggests shared mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders that are independent of BMI,” write the researchers.

The findings reinforce the significance of treating early-onset anorexia nervosa and ARFID as distinct disorders, while emphasising similarities and differences with other mental health conditions.

The findings improve our understanding of how eating behaviors and brain structures are linked, informing development of potential treatments. These disorders are currently tackled in a variety of ways, including both dietary and psychological treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

We know the relationship between the brain and our behaviors – including eating habits – is complex and multi-faceted, and the researchers are keen to keep studying how this applies to eating disorders, which could include gathering data on larger samples of people and tracking brain changes over time.

The research has been published in Nature Mental Health.

Source link