The results held steady for up to three months after the stimulation and coaching ended.

“One person had 3,000 daily steps in the beginning of the study, but she improved to 10,000 steps in the end,” said On-Yee Lo , an assistant scientist at the Hinda and Arthur Marcus Institute for Aging Research at Hebrew SeniorLife, and the study’s lead author.

The 10,000-stepper told researchers she felt like she got her “exercise high” back, Lo said.

“But I have to say,” Lo added, “this is not everyone that has this superstar type of behavior.”

Lo’s team studied 28 older adults, ranging in age from 67 to 94 years old, with more than half 80 or older. All but three were women, and all were living in subsidized housing. The setting was chosen because older adults, particularly in subsidized housing, often don’t have easy access to exercise facilities and may be less motivated to work out.

The participants received the counseling and the brain stimulation at home, an attempt to remove barriers to treatment. The stimulation was delivered in ten 20-minute sessions over two weeks, and counseling was provided four times over two weeks.

Both groups received counseling, but only half received the brain stimulation, which used a current as low as you’d find in a home smoke detector. The other half received a placebo: a similar cap that delivered a tingling sensation but didn’t include electrical current.

The group that received the electrical stimulation increased their step count by more than twice the increase seen in those who received placebo, Lo said.

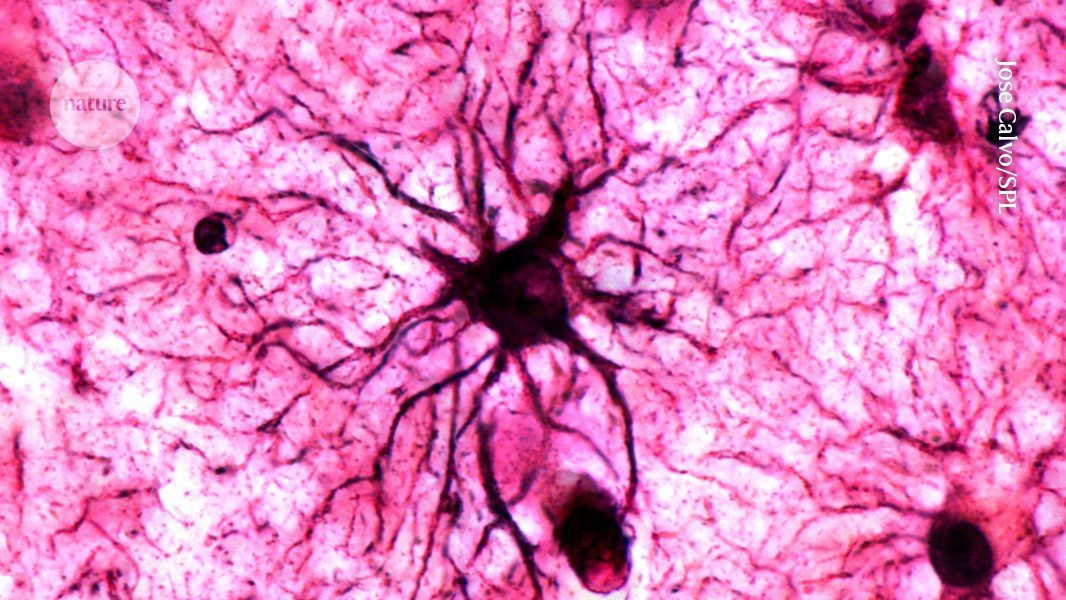

The researchers stimulated participants’ left front portion of the brain, known as the prefrontal cortex, what Lo calls the ”CEO of our brain,” because it’s more directly linked to problem solving and directing physical behavior.

Among the participants who received the electrical stimulation was 87-year-old Mimi Katz, a Brookline resident who doesn’t recall feeling any tingling sensations, but one memory is crystal clear.

“After the first [brain stimulation session], I thought, yes I am going to exercise. There is not a doubt in my mind,” Katz recalled.

Katz is the “superstar” participant who increased her daily steps to about 10,000 daily for weeks after the study. She’s still walking, though not sure if it’s as much as before. The only downside to the electrical stimulation, she said, was the gel they put on her scalp where the electrodes were placed.

“They have to put all this gunk on so the electrodes stick, which means you have to wash your hair after every treatment,” she said. “But that’s not terrible.”

While electrical stimulation research is gaining steam, an older cousin to it — magnetic brain stimulation — was approved by federal regulators for clinical use to treat major depression 17 years ago. It has since been cleared for other uses, including for treatment of migraine headaches and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Electrical stimulation, a newer field of research, has not yet received federal clearance for clinical use.

Researchers say both electrical and magnetic stimulation, which applies magnetic pulses to the scalp, stimulate nerve cells in the brain, called neurons.

Dr. Felipe Fregni, a professor of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Harvard Medical School, said stimulating such nerve cells seems to be a more effective approach for treating chronic pain, such as with fibromyalgia, rather than trying to dull the pain with analgesic medications.

That’s because an analgesic can have a boomerang effect, he said, at first decreasing nerve signals. But then a patient’s neurons try to react to that, and fire up again.

But stimulating neurons, Fregni said, seems to help regulate chronic pain by initially overactivating the neurons involved in pain processing, and then the neurons relax, bringing down the pain circuit.

His recent study used electrical brain stimulation, along with exercise, and pain education for 112 women with fibromyalgia, and found the approach effective for helping to manage pain. The researchers taught the participants how to operate the brain stimulation device at home, and they were instructed to do this five times a week for four weeks.

Fregni said the pain relief benefits started to decrease four weeks after the treatments ended.

“Whatever is causing fibromyalgia, [brain stimulation] is not reaching the cause of whatever may lead to dysfunction in brain plasticity,” he said. The stimulation “is trying to balance the plasticity, trying to create an environment to better decrease pain, but whatever is causing it is still there.”

Dr. Rodrigo Machado-Vieira, a psychiatry professor at the McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston, was lead researcher in a study published last year involving 174 adults with moderate to severe depression.

They were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: electrical brain stimulation, or inactive stimulation, which used the same device but did not provide a current. Participants were taught how to use the device at home and followed a 10-week course of treatment. Those who received the electrical stimulation showed significant improvements in the severity of their depression, compared to those who used the inactive device.

Machado-Vieira said some patients respond better to electrical versus magnetic stimulation, and vice-versa, but researchers still don’t understand why. One benefit of electrical rather than magnetic, however, is that the electrical devices being tested now are much smaller and lighter than the magnetic ones typically only used in doctors’ offices.

Machado-Vieira and other scientists said getting federal regulators to approve small electrical stimulation devices that can be used at home would make the treatment more widely accessible.

“In terms of convenience for people who live far away, or who cannot travel to sessions at the clinic, that’s a clear advantage of the [electrical devices], but that doesn’t mean that they are going to respond better to that,” compared to magnetic stimulation, he said.

Machado-Vieira also said brain stimulation alone, without medications, is probably not powerful enough to treat major depression. But he understands as a clinician who has long treated patients, that some just won’t stick with their medications.

“Psychiatric medications have some level of stigma,” he said. “There are some groups of patients who really are not willing to take antidepressants and would benefit from this [brain stimulation] type of intervention.”

Kay Lazar can be reached at kay.lazar@globe.com Follow her @GlobeKayLazar.