An odd shape in the South Pacific that has sparked the latest push to solve one of the greatest mysteries of all time came to light in a backyard in California. US Navy veteran Mike Ashmore was at home in 2020, scrolling through satellite images of a tiny island called Nikumaroro, when he spotted the unexpected object in a lagoon.

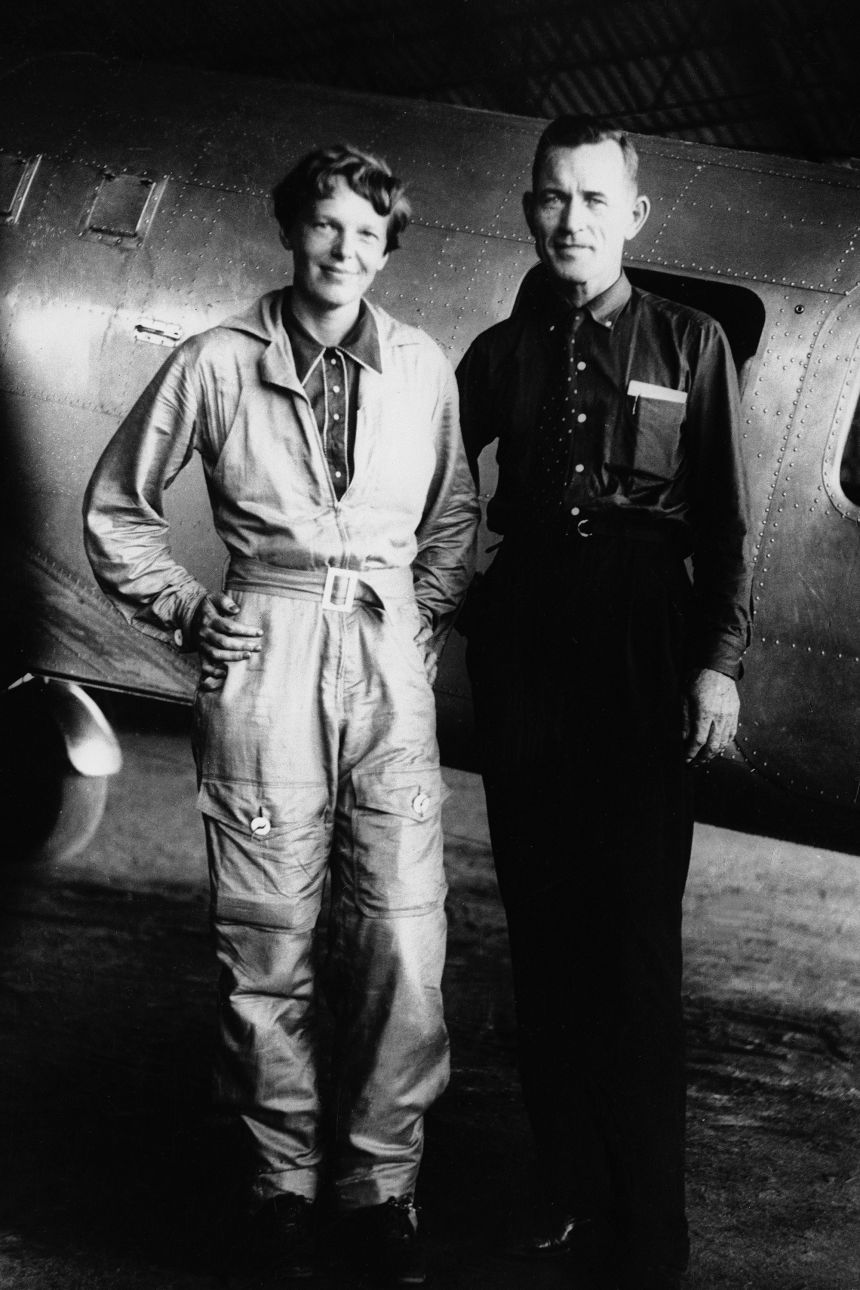

Halfway between Australia and Hawaii, Nikumaroro plays a key role in one of two rival hypotheses that seek to explain what happened to the famed aviator Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, who went missing in 1937 while attempting to fly around the world. Their disappearance has captivated researchers for decades and long fascinated Ashmore, a hobbyist who got hooked by a theory that the legendary pilot ended up on the island’s shores.

“It was Apple Maps on my iPhone,” Ashmore recalled about the digital exploration that led to his find. “I was sitting on a swing in the morning having coffee with my dog. The day before, I went around the exterior of the island, and that morning I started going around the lagoon and something caught my eye. Then I looked closer, and I snapped a screenshot of it.”

Ashmore thought what he saw resembled an aircraft wing and shared the picture with a popular Amelia Earhart online forum hosted by The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery, or TIGHAR, a collective devoted to aviation history and archaeology. The elongated shape in the satellite imagery stirred excited discussion among members, although some said it was likely a log from a palm tree.

The blurry object also caught the attention of archaeologist Rick Pettigrew, a longtime Earhart aficionado and executive director of the Archaeological Legacy Institute in Eugene, Oregon, who decided to investigate further. He said he found that the anomaly, which has since been named the Taraia Object, is visible in other aerial photos taken of the lagoon, including some captured as far back as 1938.

“With the evidence that we have now, it would be a crime for nobody to go there and look,” Pettigrew said.

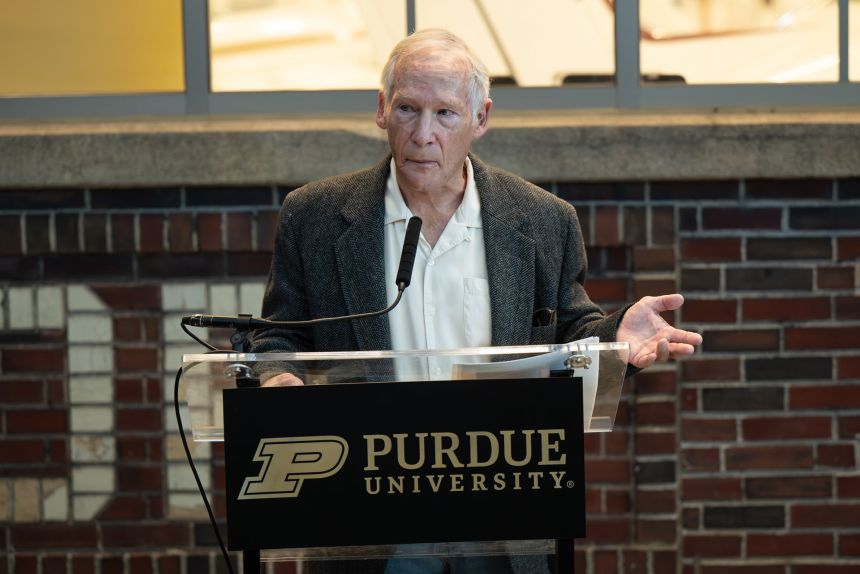

Now an expedition is launching to do just that. Led by Pettigrew and Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, where Earhart once worked in the department of aeronautics, the new effort will make a dash straight for the Taraia Object, in the hopes it could uncover part of Earhart’s plane. Ashmore said he intended to join the journey but has been forced to drop out because of family illness.

The team is set to depart from Majuro in the Marshall Islands on November 4 and sail about 1,200 nautical miles to Nikumaroro. From there, researchers will spend around five days on the small island investigating the intriguing object in the lagoon.

If they find what they’re looking for, it could lead to a landmark discovery. But the idea that Earhart ended up an island castaway is far from widely accepted, and another team of researchers is racing to close in on proof of an alternate explanation.

Earhart and Noonan disappeared on July 2, 1937, while seeking Howland Island, nearly 400 miles (644 kilometers) northwest of Nikumaroro.

Howland was a planned refueling stop on their attempt to circumnavigate the globe, a journey that had dominated news headlines and gripped the public imagination.

One school of thought — and the official determination made following the massive US government-led search conducted immediately after they disappeared — suggested that Earhart and Noonan ran out of fuel and their Lockheed 10E Electra crashed into the Pacific Ocean near their intended destination.

It’s a theory that has already informed several searches over the years, including a 2024 attempt by ocean exploration company Deep Sea Vision that ultimately turned up some rocks formed in the shape of a plane.

Guided by a new analysis of Earhart’s radio communications on the day she vanished, Maine-based ocean exploration company Nauticos plans to embark on a fresh search of the ocean floor near Howland Island next year. The expedition will be the company’s fourth attempt to locate the plane, but it says the new findings have dramatically narrowed the search area, potentially increasing its chances of success.

Pettigrew and others believe that Earhart and Noonan landed their Electra safely on Nikumaroro, then known as Gardner Island. There, proponents of this hypothesis suggest, the duo made repeated distress calls for help using the radio on the plane, but subsequently died of thirst or hunger.

However, at least five expeditions to the island and the surrounding waters since 2010 have failed to find definitive proof that Earhart and Noonan were castaways. Pettigrew took part in one expedition in 2017. Another, in 2019, involved oceanographer and National Geographic explorer-in-residence Bob Ballard, who found the Titanic wreck in 1985.

The Nikumaroro theory is more plausible than some alternatives that have been put forward over the years to explain Earhart’s disappearance, according to Dorothy Cochrane, who recently retired as curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. (A 2017 documentary even suggested Earhart died a Japanese prisoner.) Cochrane said the likeliest explanation is the simplest: Earhart ran out of fuel and crashed into the Pacific Ocean.

President Donald Trump spurred renewed interest in the decades-old mystery earlier this month when he ordered the release of records about Earhart and her final trip, although it’s not clear what prompted his sudden focus on the topic — or whether there are even any records to be declassified. No new records have been released, according to CNN’s reporting.

The US National Archives holds publicly available information about the search for Earhart and Noonan, including her last communications with the Itasca, a US Coast Guard vessel tasked with supporting her flight, Cochrane said.

“She was an enormously popular figure of the era, all of her flights were followed by the public, and she earned her living by making these flights as a woman in the 1930s when there were really no avenues for women to be in aviation,” Cochrane added.

Fringed with a coral reef and located in what’s now the Republic of Kiribati, Nikumaroro is roughly 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) long and 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) wide and was uninhabited when Earhart and Noonan made their final flight. The atoll was briefly occupied between 1938 and 1963 when the British colonial administration encouraged people to settle there from the nearby southern Gilbert Islands.

The castaway hypothesis draws on the work of Ric Gillespie, the founder of TIGHAR and author of 2024 book “One More Good Flight: The Amelia Earhart Tragedy.” He has visited Nikumaroro 11 times, turning up possible clues and fragments of evidence.

In Gillespie and Pettigrew’s telling, after failing to find Howland Island, Earhart headed south and landed the Electra on Nikumaroro’s large coral reef, which is exposed at low tide. There, she and Noonan sent distress signals and lived off rainwater and caught fish and turtles for days, perhaps weeks, until they died. Their remains were likely eaten by huge coconut crabs that inhabit the atoll, leaving behind a few bones, some artifacts and the remains of fires.

Several lines of evidence support the theory, according to Gillespie and Pettigrew.

Radio bearings, or directions, tracked on signals emitted in the wake of the plane’s disappearance appeared to have crossed in the vicinity of Nikumaroro, although it’s not clear or confirmed whether these were really from Earhart.

Bones found on Nikumaroro in 1940 were sent to Fiji, where they were assessed by a medical doctor as being male before going missing, Gillespie said. But analysis of the bone’s measurements, which were recorded at the time, using modern forensic software suggests the remains belonged to a woman, and they could be a potential match with Earhart.

Artifacts found on the island include a woman’s mirror compact similar to one Earhart was known to carry, a cosmetic jar, a jackknife, and a wooden box that appeared to once contain a sextant, a navigation instrument.

Gillespie, however, does not believe the object Ashmore identified in the lagoon is Earhart’s plane. He said he has visited the location in the lagoon where the object is located and noticed nothing out of the ordinary.

“Looking at the later satellite imagery, something did show up there, but it’s very clearly a tree. Specifically, it’s a pandanus tree,” Gillespie said. “They grow along the lagoon shore, and it’s not unusual in a big storm for trees to wash in and wash out.”

Gillespie still believes Nikumaroro is where Earhart spent her final days but doesn’t think there is anything more to be found on the island.

“Everybody wants the airplane. The airplane is gone,” he noted. “We think the airplane was washed into the ocean, probably on July 7, best we can calculate, and almost immediately destroyed in the surf, pounded against the reef edge.”

For Pettigrew, however, the Taraia Object is the final puzzle piece that will solve the mystery of Earhart’s disappearance. He said he believes the team will find the aluminum wreckage of her Electra plane.

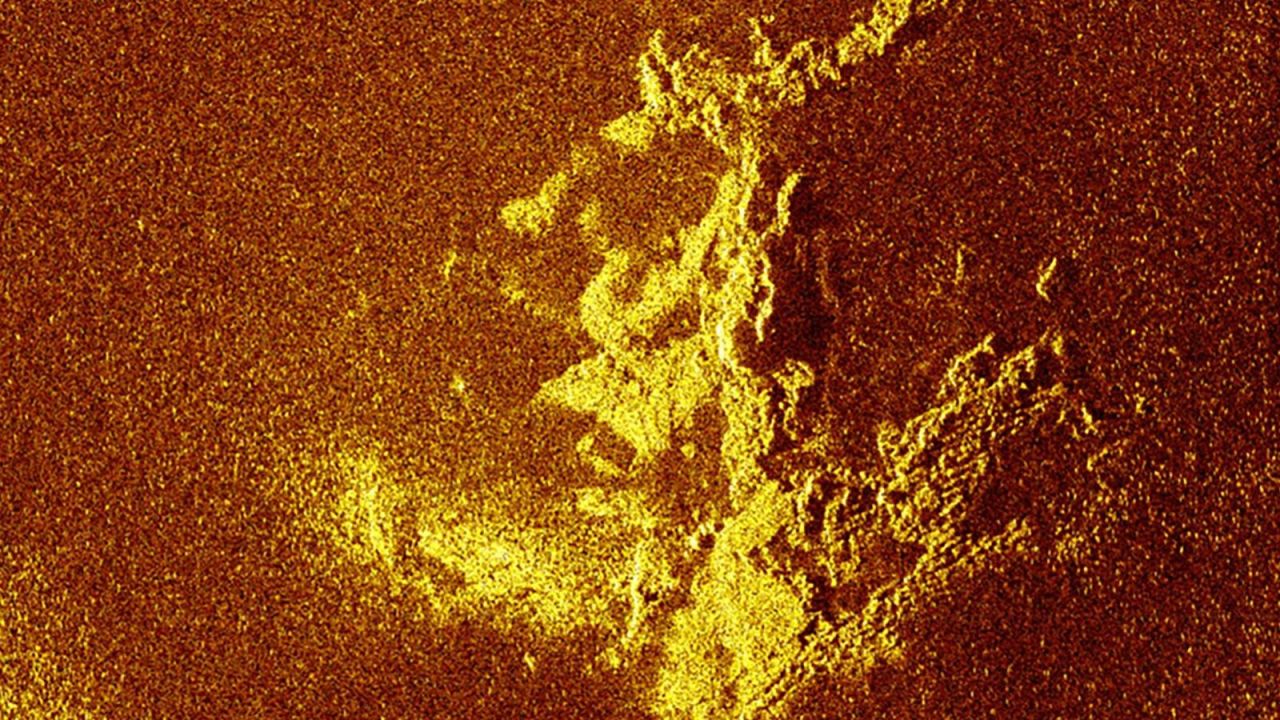

Once on the island, Pettigrew and the team of 14 researchers plan to take video and still images before using sonar and magnetometers to investigate the object. Only then will the researchers begin to excavate using a hydraulic dredge.

“I think we have a really good chance of delivering an exciting announcement,” Pettigrew said.

“I’ve reviewed this evidence backwards and forwards, over and over,” he added. “I’ve answered multitudes of questions, I’ve looked at all the objections that people can throw at me, and I have an answer for all of it.

It’s very strong.”

Dave Jourdan, president of Nauticos, which will focus its search on the deep ocean around Howland Island, doesn’t regard Pettigrew’s expedition as competition in the quest to uncover what happened to Earhart.

“They’re barking up a different tree,” Jourdan said. “The primary data from the Coast Guard, and our radio signal analysis, just does not support that at all.”

Three Nauticos expeditions since 2002, along with ground covered by a 2009 expedition led by the Waitt Institute for Discovery, have, in total, covered 3,610 square miles (9,350 square kilometers) — an area roughly the size of Connecticut. The Nauticos researchers hope to embark on a final expedition next year, although they are still trying to raise the $8 million to $10 million necessary to fund it.

“In past searches, we focused on the north, the northwest of the island for many, many reasons …, but we searched it, and she’s not there,” he said. “So that leaves a couple of other options, and we believe that with one more expedition, we should be able to fill out all of those areas.”

Jourdan’s colleagues tracked down and reconstructed the exact make and model of radio used by Earhart and the Itasca vessel, which was waiting for the pilot off the shores of Howland Island.

Using the radio in a plane similar in size to the Electra, Nauticos in 2020 recreated the last hours of Earhart’s flight and determined she and Noonan’s approximate location at 8 a.m. on the day they vanished. Jourdan said his team now has the most precise information to date about the duo’s final position before their disappearance.

“One of the things that is very telling is on her second to last transmission, she reported hearing the Coast Guard, and that information, along with our knowledge of the frequency she was hearing them on and the equipment she was operating gave us a very solid number of how far she was from the island at that time,” he explained.

The Nauticos team members plan to use four autonomous underwater vehicles to search the seafloor in areas they have identified, Jourdan said. Recent improvements in technology, such as longer battery life and new sonar techniques, will allow the team to cover more ground than in previous expeditions.

“We can’t make the ocean transparent, so we still have to go down there to get good, high-quality data, but we can stay there longer and navigate more accurately,” he said. “Sharp-edge metal objects tend to be very bright in the sonar, so we are confident that if it’s there, we’ll see it.”

Earhart, Jourdan said, represents a spirit of adventure and exploration, “of trying your best in spite of the odds, and doing things that other people dare not to do, and doing them as a woman.” Nearly a century after her disappearance, it’s clear that tracking down the renowned aviator’s plane, and her final resting place, is a pursuit that never gets old.

Ashmore became captivated by Earhart’s story when he heard it from a teacher in first grade. “It just stuck with me,” he said. “It wasn’t like I thought about it every day or anything like that, but I never forgot about it.”

Even if the upcoming expedition led by Pettigrew determines the object he found while scrolling through his phone during pandemic downtime isn’t Earhart’s plane, Ashmore said he would not give up the search.

“You can call this my hobby,” he said. “I’ve enjoyed it. … I’m going to continue. Someone is going to find her.”

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Source link