A better understanding of dementia risk can lead to improvements in care and in treatments, and a new study identifies a link between changes in brain shape and declines in cognitive functions – such as memory and reasoning.

The idea is that some of the wear and tear that eventually leads to dementia can also alter the brain’s structure and shape, and looking out for these shifts could be a relatively simple way of revealing dementia early.

These new findings are from researchers at the University of California, Irvine (UC Irvine) and the University of La Laguna in Spain, and they build on what we already know about how the brain naturally shrinks as we get older.

Related: Artificial Neuron That ‘Whispers’ to Real Brain Cells Created in Amazing First

“Most studies of brain aging focus on how much tissue is lost in different regions,” says neuroscientist Niels Janssen, from the University of La Laguna.

“What we found is that the overall shape of the brain shifts in systematic ways, and those shifts are closely tied to whether someone shows cognitive impairment.”

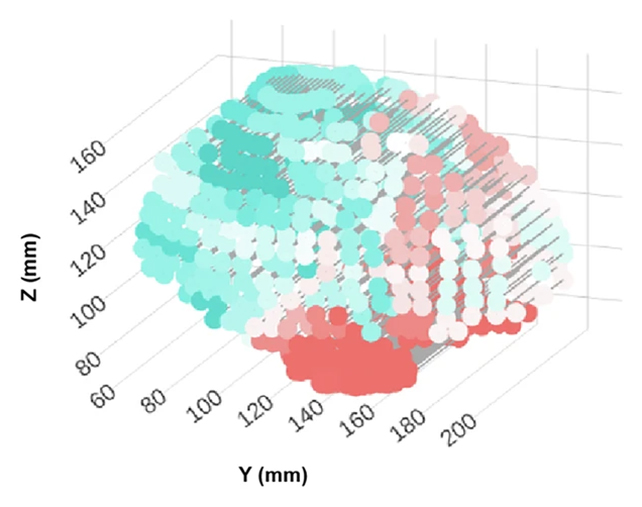

The team analyzed 2,603 MRI brain scans from people aged from 30 to 97, tracking structural and shape changes over time and mapping them against participants’ cognitive test scores.

Age-related expansions and contractions in brain shape weren’t even across all the brain regions, the researchers found, and in those people experiencing some level of cognitive decline, the unevenness tended to be more noticeable.

For example, areas of the brain towards the back of the head were shown to shrink with age, and especially for those who scored lower on reasoning ability tests. A lot more data is going to be required to establish these relationships more precisely, but this study suggests they exist.

There are further implications for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, where brain damage accumulates.

The researchers propose that a crucial memory hub called the entorhinal cortex may be put under pressure by age-related shape shifts – and that’s the same region where toxic proteins linked to Alzheimer’s typically start congregating.

“This could help explain why the entorhinal cortex is ground zero of Alzheimer’s pathology,” says neuroscientist Michael Yassa, from UC Irvine. “If the aging brain is gradually shifting in a way that squeezes this fragile region against a rigid boundary, it may create the perfect storm for damage to take root.”

“Understanding that process gives us a whole new way to think about the mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease and the possibility of early detection.”

More brain scans and more precise measurements will help progress this research further. The team is keen to explore why some brain areas may expand with age and how this relates to cognition.

The takeaway: it’s evidence that it’s not just the brain volume that matters in health and aging, but also the 3D shape of the brain – made up of many different regions all working together to keep our minds sharp and active.

“We’re just beginning to unlock how brain geometry shapes disease,” says Yassa. “But this research shows that the answers may be hiding in plain sight – in the shape of the brain itself.”

The research has been published in Nature Communications.

Source link