Dr. Uri Manor feels like much of his early life was blessed by fate.

Born with genetic hearing loss that enables him to hear only about 10% of what others might, Manor was diagnosed at age 2, when he happened to be living in Wichita, Kansas – the home of what he describes as “one of the most advanced schools for children with hearing loss, maybe in the world.”

“It wasn’t clear if I would ever learn language, if I would ever be able to speak clearly,” said Manor, now 45. “So I was very lucky, really weirdly lucky, that we were living in Wichita, Kansas, at the time.”

Working in Wichita with experts at the Institute of Logopedics, now called Heartspring, Manor learned to speak.

That same sort of serendipity led Manor into an unexpected career studying hearing loss himself, first at the US National Institutes of Health and, now, leading his own lab at the University of California, San Diego, where his research into ways to restore hearing was supported by a major five-year NIH grant.

But that’s where Manor’s luck ran out. His grant was terminated in May by the Trump administration as part of its policies targeting diversity, equity and inclusion, or DEI, initiatives; Manor’s funding had been awarded through a program that aimed to promote workforce diversity, for which he qualified because he has hearing loss.

Now, Manor’s research is in limbo, like that of thousands of other scientists whose work is supported in large part by the federal government and who’ve been affected by grant terminations. And the halt comes as research into hearing loss, which affects as many as 15% of American adults and 1 in 400 children at birth, had recently shown signs of rapid advancement.

It was intense curiosity about the world that led Manor into a career in science, where early on, fate seemed to strike again. As a researcher at the NIH and Johns Hopkins working toward his Ph.D., Manor hoped to find an adviser interested in how magnetic fields could influence cells – an obsession that stemmed from a fascination with animals’ ability to navigate using magnetic fields of the Earth.

“I was describing that to a physicist PI [primary investigator] at the NIH, and he goes, ‘Yeah, I can’t support that project, but what you’re describing sounds a lot like the hair cells of the inner ear. You should go talk to this PI, who studies hair cells,’” Manor recalled.

Despite spending much of his time at the audiologist’s office, he said, “I’d never thought about the ear.”

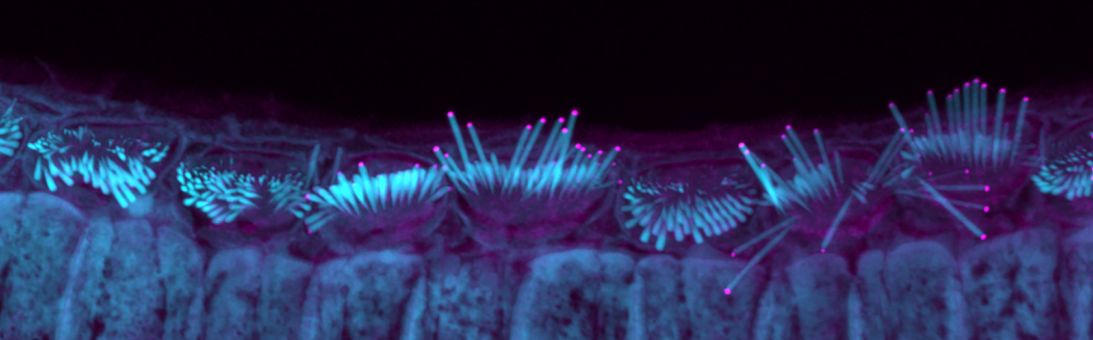

That PI, Dr. Bechara Kachar, showed him microscope images of hair cells in the inner ear, which enable us to hear, and Manor remembers being stunned.

“I fell in love with the hair cell, these mysterious cells in our ear, because the system was so amazing, how it all comes together and how it all works,” Manor said. “I got goosebumps. I have hearing loss, and I never thought about studying it. But now I was in this room falling in love with this system. I was like, ‘What if this is like my destiny? What if this is what I’m supposed to be doing?’”

In 2023, Manor received his first R01 grant from the NIH, a major five-year award that would support his lab’s work on ways to restore hearing. Again, serendipity had struck; the R01 grant process is intensely competitive, funding only a fraction of the applications the biomedical research agency gets. Young researchers are advised to apply to research funding programs where they may have a unique edge, to improve their odds, Manor said.

There was one that seemed a perfect fit; he was encouraged by mentors to apply to a program at the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders that aimed to promote workforce diversity. It was specifically designed to support early-stage researchers “from diverse backgrounds, including those from underrepresented groups,” such as people with disabilities. Manor qualified because he has “congenital severe-to-profound hearing loss,” he said. “It felt right.”

Even at the time, Manor said, he acknowledged the risk that government initiatives supporting DEI may not always be popular. His biggest concern, though, was that he might not be able to renew his grant through the same program after its five years were up.

But his luck turned. In late May, he received notification from the NIH that, only two years in, his five-year grant had been canceled. The reason: The Trump administration was targeting programs promoting DEI.

“Research programs based primarily on artificial and non-scientific categories, including amorphous equity objectives, are antithetical to the scientific inquiry, do nothing to expand our knowledge of living systems, provide low returns on investment, and ultimately do not enhance health, lengthen life, or reduce illness,” the notice read. “It is the policy of NIH not to prioritize such research programs.”

No more funding would be awarded, it continued, and all future years on the grant had been removed.

“No one ever imagined that a grant could be canceled in the middle of an award period,” Manor said. “It might be naïve and incorrect, but when you get a five-year grant from the NIH, that’s a five-year contract, and you make plans based on five years. … That’s really kind of rocked our world.”

A spokesperson for the NIH told CNN: “The study itself has value, however unfortunately it was funded under an ideologically driven DEI program under the Biden Administration. In the future, NIH will review, and fund research based on scientific merit rather than on DEI criteria.”

Manor spent the next two weeks sleeping two to three hours a night, writing new grant proposals to try to replace the lost funds. But the termination meant his lab had to stop experiments, some of which had taken years to set up. Manor took that measure in an attempt to avoid having to lay off staff members – which he ultimately had to do as well.

Hearing loss affects more than 30 million people in the US, with prevalence rising as people age. Recently, the field has taken leaps forward, with trials of gene therapies, which deliver working copies of genes to make up for mutated ones that cause deafness, helping children hear for the first time.

“We’re at the threshold of a brave new world, so to speak,” said Dr. Charles Liberman, a senior scientist and former director of the Eaton-Peabody Laboratories at Mass Eye and Ear, one of the largest hearing research laboratories in the world. “It’s pretty incredible, the progress that’s been made in the last 10 or 15 years, on understanding what goes wrong in the ear and having a pretty good handle on what kinds of approaches might work to cure sensorineural hearing loss.”

Liberman anticipates breakthroughs in the next five to 10 years in slowing age-related hearing loss as well and, “perhaps farther in the future, to actually reverse age-related hearing loss.”

Liberman said Manor – with whom he’s collaborated in the past – is contributing to the field’s advancements.

“He has not been in the field for terribly long, but he’s already made a big impression because of the incredible sort of computational approaches he takes to analyzing data from the inner ear,” he said.

“His grant got cut because it was a diversity initiative,” Liberman continued, “but Uri’s research is top quality, and I’m sure it would have been funded just on its own merit.”

Manor’s was one of thousands of NIH grants cut by the Trump administration, amounting to almost $3.8 billion in lost funding, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. Others canceled under the banner of combating DEI ideology include those focused on HIV, where researchers reported receiving notification identical to Manor’s.

But recently, Manor’s fortunes seemed to have changed again. A federal judge ruled in June that it was illegal for the Trump administration to cancel several hundred research grants in areas including racial health disparities and transgender health. Manor’s is among the grants included, and he received notice that the funding should come through.

Still, he said he worries about whether that decision will hold through future court challenges. And he, like so many other scientists affected by the administration’s drastic cuts to research funding, warns about the effects on scientific progress.

“No matter what your political leanings are, you have a 1 in 400 chance of having a child with hearing loss,” he said. Anyone dealing with medical conditions “will benefit from the amazing advances of science and our biomedical research force.”

But he also emphasized the importance of recognizing that research like his is supported by taxpayers, some of whom “are struggling to pay their own bills, who are struggling to pay their kids’ doctors bills.”

“And some of their taxpayer dollars are coming to my lab,” he said. “That’s a huge responsibility and privilege, and we have to make sure we’re doing good with it. For me, that’s a really powerful motivating factor, and I would like to believe that we’re doing it.”