When the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety’s “SORB,” the Small Overlap Rigid Barrier test, launched in 2012, many automakers were caught flat-footed, with vehicles that had been Top Safety Picks now scoring poor ratings in the new test. SORB was a humongous shakeup for the car world, with automakers all redesigning their vehicles to handle the challenge — sometimes at significant financial and package-space/design cost. But now, over a decade later, it’s not SORB or its cousin passenger-side-SORB that challenge automakers most, it’s the new updated Moderate Overlap Test. Here’s why.

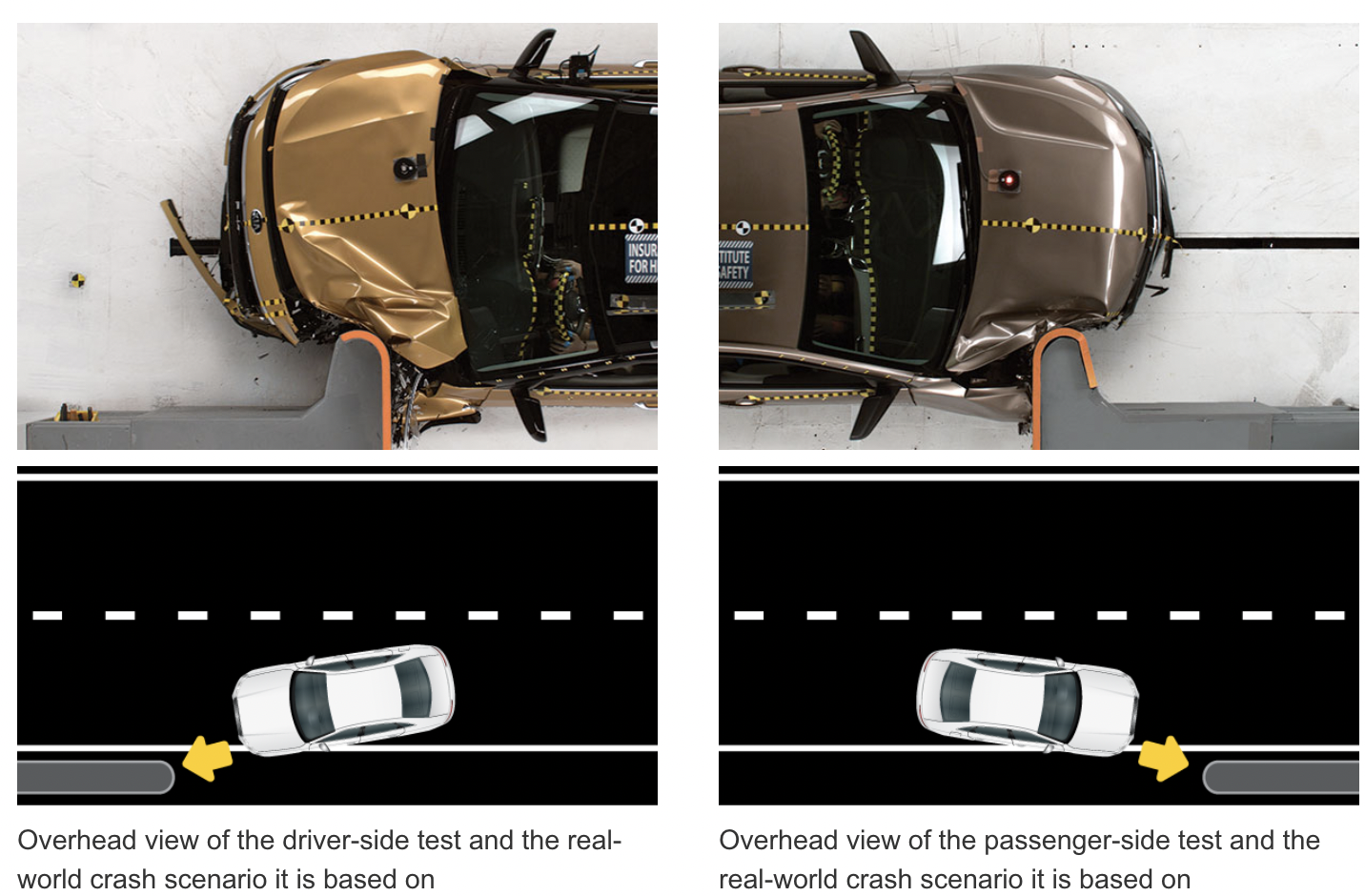

I used to feel weird about new automotive crash tests, mostly because there’s really no limit to how many crash tests an organization can create, and the testing organizations have incentive to keep the new tests coming. At a certain point, we could all be driving bankvaults on wheels, and that’s no fun, I used to think. I’ve changed my mind on that, because many modern crash tests make sense. IIHS’s Small Overlap Rigid Barrier test, for example, is clearly a common crash scenario: Either two vehicles in opposing lanes crash after one drifts over the line, or one vehicle drifts into a pole or a tree or a barrier — it’s not a farfetched scenario by any stretch:

![]()

Up until SORB, the hardest crash test a vehicle in the U.S. had to pass was the moderate overlap crash test. It’s similar to SORB in that only a small portion of the front end of a vehicle hits a barrier, but instead of 25 percent like in SORB (shown above), it’s 40 percent (shown below). With more of the vehicle’s structure able to protect the occupant against the barrier, this was generally a test that automakers passed more easily than SORB.

The Small Overlap test (SORB) was a severe challenge cars in the early-mid 2010s, as those vehicles hadn’t been designed with provisions for such a severe outboard vehicle impact. Here’s a 2014 IIHS study of some mid-size SUVs, many of which got completely annihilated by the new SORB test:

Just look at how difficult it was for the Mazda CX-9’s safety cage to handle all those loads imparted so far outboard:

Here’s a look at the same test, but this time run on small cars:

My goodness look at how badly the Kia Soul’s structure collapses, and how much the dummy moves outboard away from the airbag due to the nature of the crash:

In time, automakers designed cars that could pass SORB, but then came the passenger-side version of the test:

As IIHS points out, automakers sometimes didn’t bolster the passenger-side to pass the test, since it wasn’t part of IIHS’s initial test:

Eventually, automakers either patched their cars up, or redesign the crash structure entirely for a new generation. The Jeep Wrangler JL, for example, clearly received a patch. Next time you see a 2022+ Jeep Wrangler, pay attention to its passenger’s side frame just aft of the front wheel. You’ll see this big bracket hanging low — a ground clearance-killing bracket that diehard off-roaders loath:

Anyway, SORB has been a big deal for a while, but recently, while chatting with IIHS’s Director of Media Relations, Joe Young, he told me that, actually, the test that many automakers are struggling with right now isn’t SORB, but the Institute’s new Modified Moderate Overlap test.

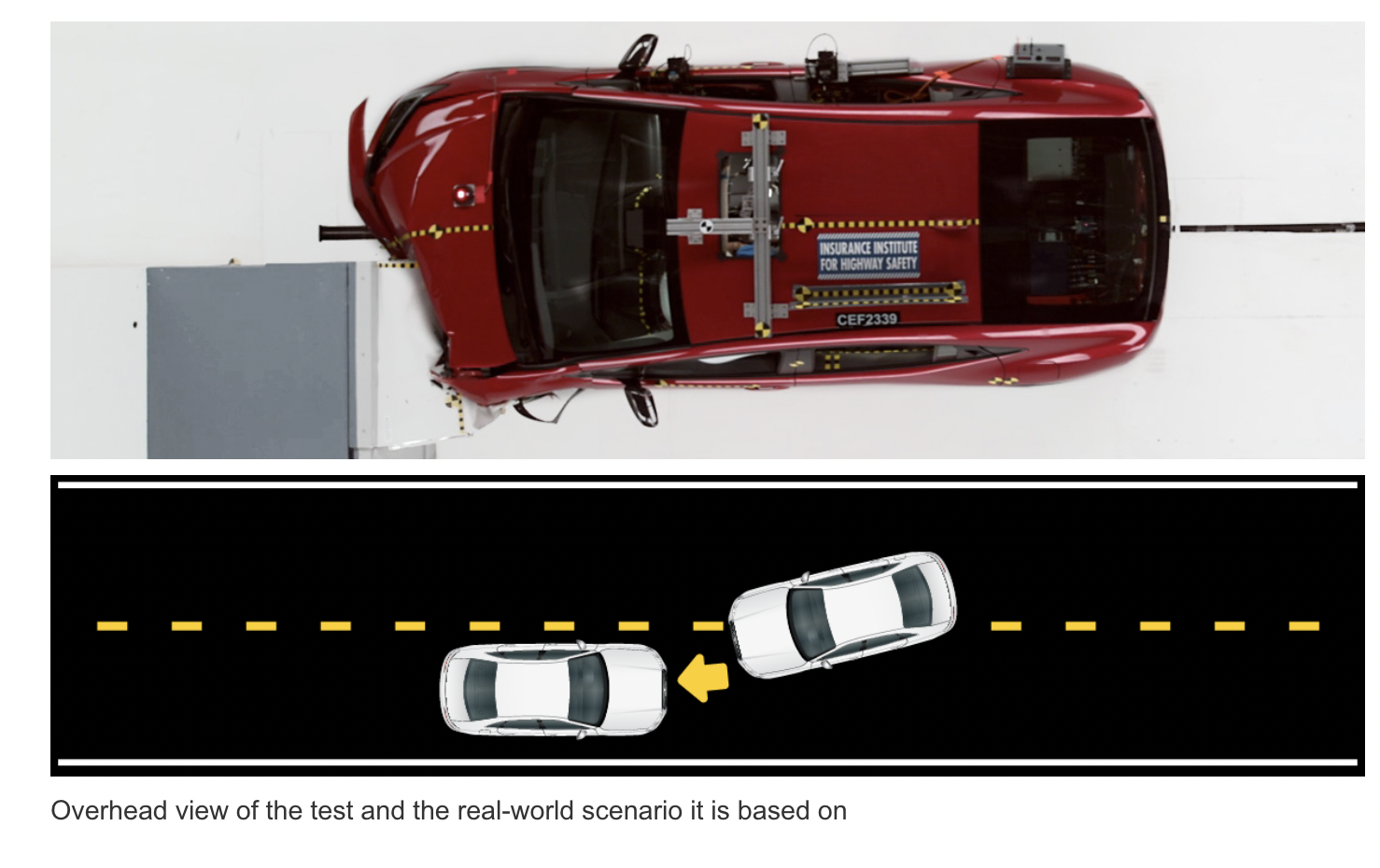

The modified Moderate Overlap test is the same as before — 40 percent of the front structure hits a rigid barrier — except now there’s a rear passenger, specifically a “smaller Hybrid III dummy representing a small woman or 12-year-old child is belted in the second-seat behind the driver.” That’s right; up until recently, frontal crash tests were only focused on the front passengers.

This topic came up with I emailed IIHS about the new Tesla Cybertruck crash tests; why had the Institute not put the Cybertruck through its hardest test, but instead the Moderate Overlap? Well, it turns out, Moderate Overlap is IIHS’s hardest test right now, with IIHS’s Joe Young telling me:

We chose the updated moderate overlap test because it’s proving to be the most challenging for new vehicles. Most new vehicles are doing fine in the side and small overlap crash tests since they’ve been around for a bit, but this one is proving challenging, and so we’re seeing a range of performance that can help consumers differentiate among models.

[…]…the front seats have gotten a lot safer in recent years thanks to crash testing that has mostly focused on these seating positions. Our new test is the first frontal crash test in the U.S. to add a dummy and related scoring metrics to the second row, which is forcing automakers to incorporate more sophisticated belt technologies into those seats and, in some cases, to redesign the rear seats. It’s proving to be challenging for some models.

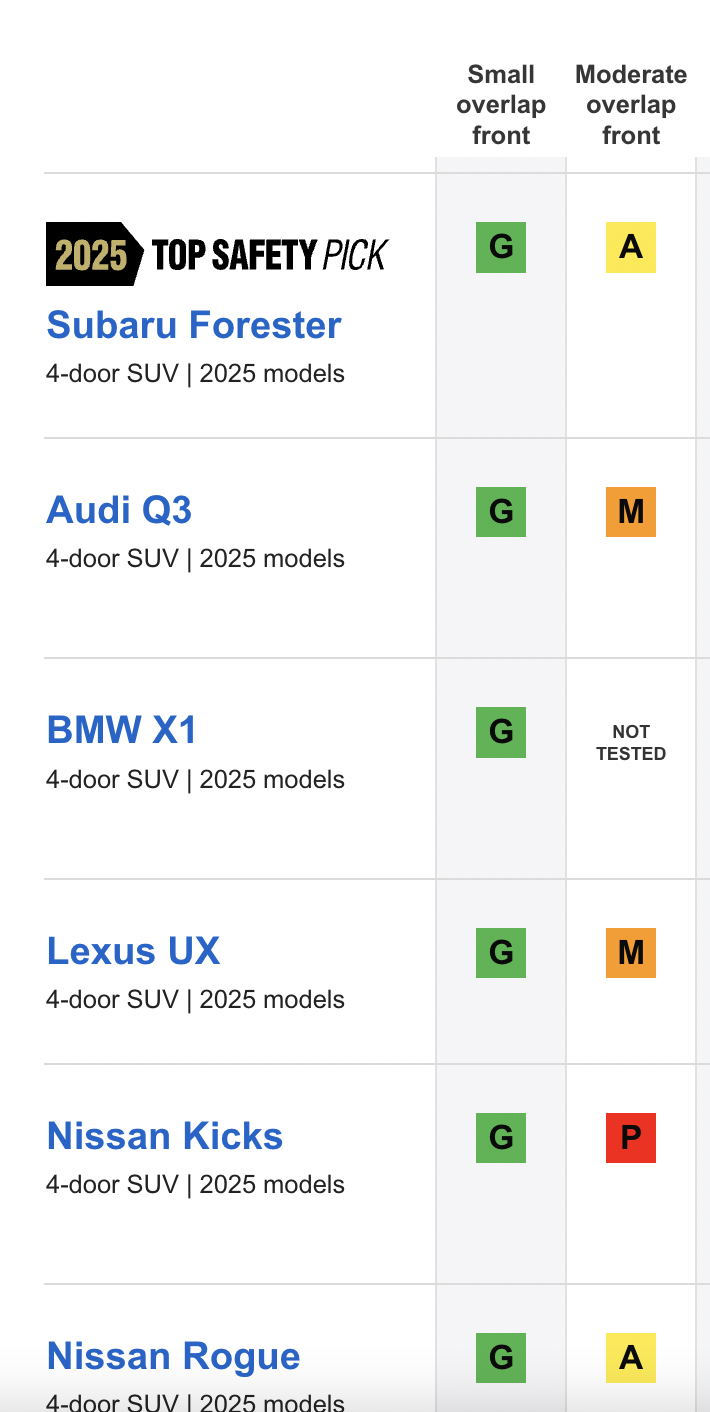

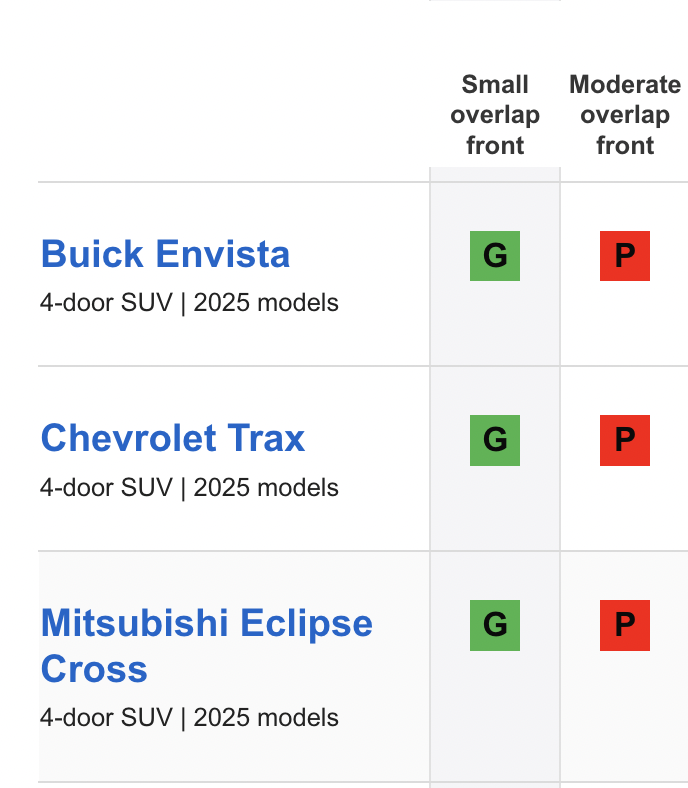

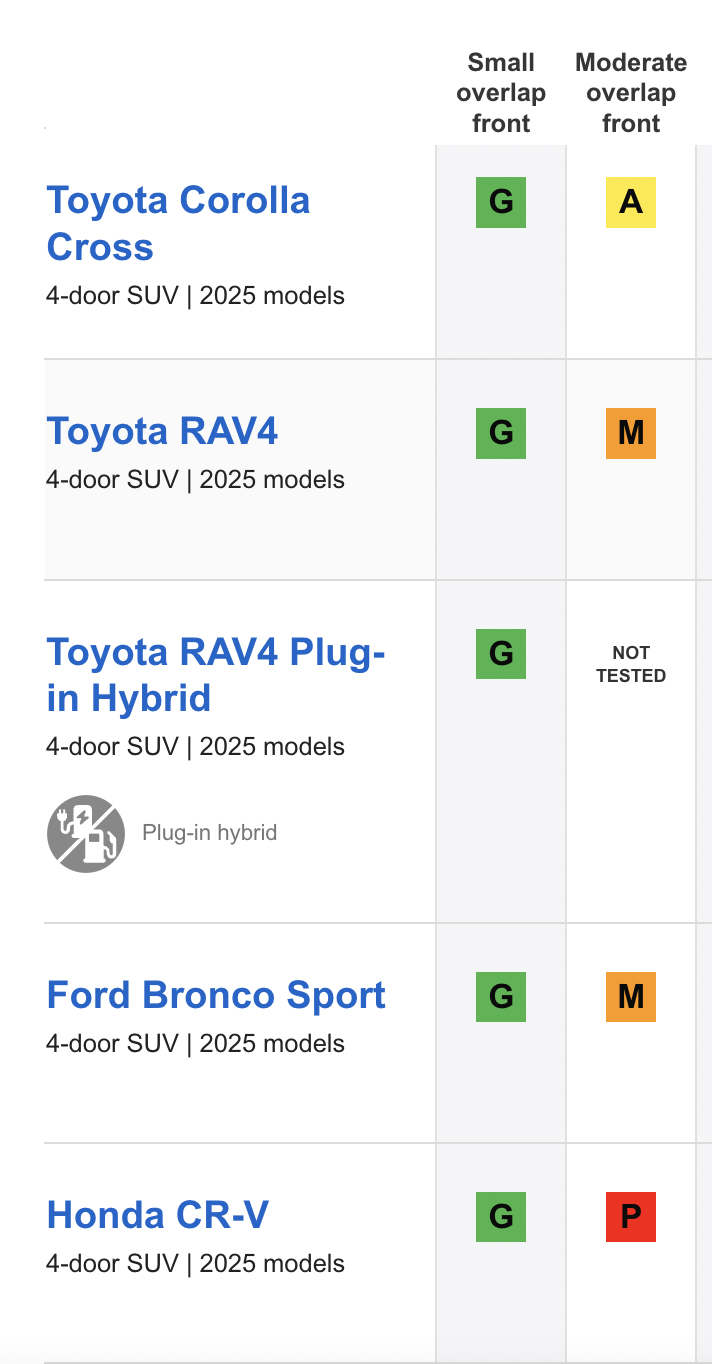

If you review the current scores by vehicle category (as an example I’ve linked small SUVs below, but you can toggle around), and focus on the three left-most columns (which are destructive tests), you’ll see that the moderate overlap test is where we’re seeing a lot of variation in scores as you scroll down.

Certainly, we are still seeing some vehicles fall short in the other crash tests. And as I mentioned, I think we will want to return to these EVs soon so we can provide consumers with important information about how they stack up in other test types.

Indeed, if you look at the Institute’s test Scores, even Subaru didn’t get a good rating on the new Moderate Overlap test, and longtime high-scorers, the Toyota Rav4 and Honda CR-V, got only marginal and poor scores, respectively.

Clearly, this test is the toughest one IIHS has today, and it comes as a result of an IIHS study of fatal crashes involving rear-seat passengers. From IIHS:

A new IIHS study of frontal crashes in which belted rear-seat passengers were killed or seriously injured suggests that more sophisticated restraint systems are needed in the back.

Front-seat occupants have benefited greatly from advancements in restraints — the umbrella term for airbags and seat belts, which work together during a crash to keep a person in the proper position and manage forces on the body. Back-seat occupants haven’t benefited from this technology to the same extent.

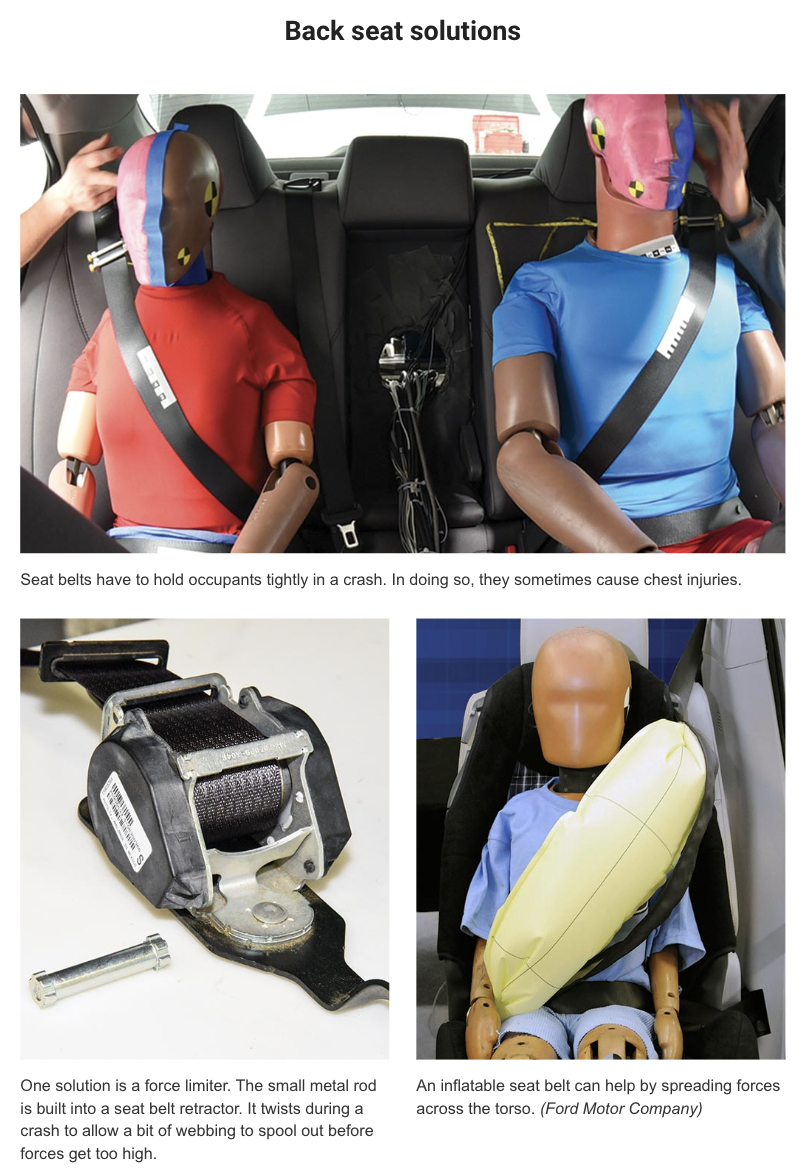

You might be thinking that, in the back seat you don’t have to worry about intrusion of the crash structure, and while that’s true, the crash forces on passenger’s back there are still enormous, and they are not mitigated by the same safety features found up front — no airbags, and oftentimes no seatbelt tensioners. From IIHS:

As soon as a frontal collision starts, seat belts in the front seat tighten around the occupants, thanks to embedded devices called crash tensioners. At the same time, the front airbags deploy within a fraction of a second. Depending on the crash configuration, the side airbags may deploy too.

The tightened belts and deployed airbags keep the front-seat occupants safely away from the steering wheel, instrument panel and other structure when the vehicle stops abruptly, even if the force of the crash pushes that structure inward. To reduce the risk of chest injuries, these belts also have force limiters, which allow some webbing to spool out before forces from the belt get too high.

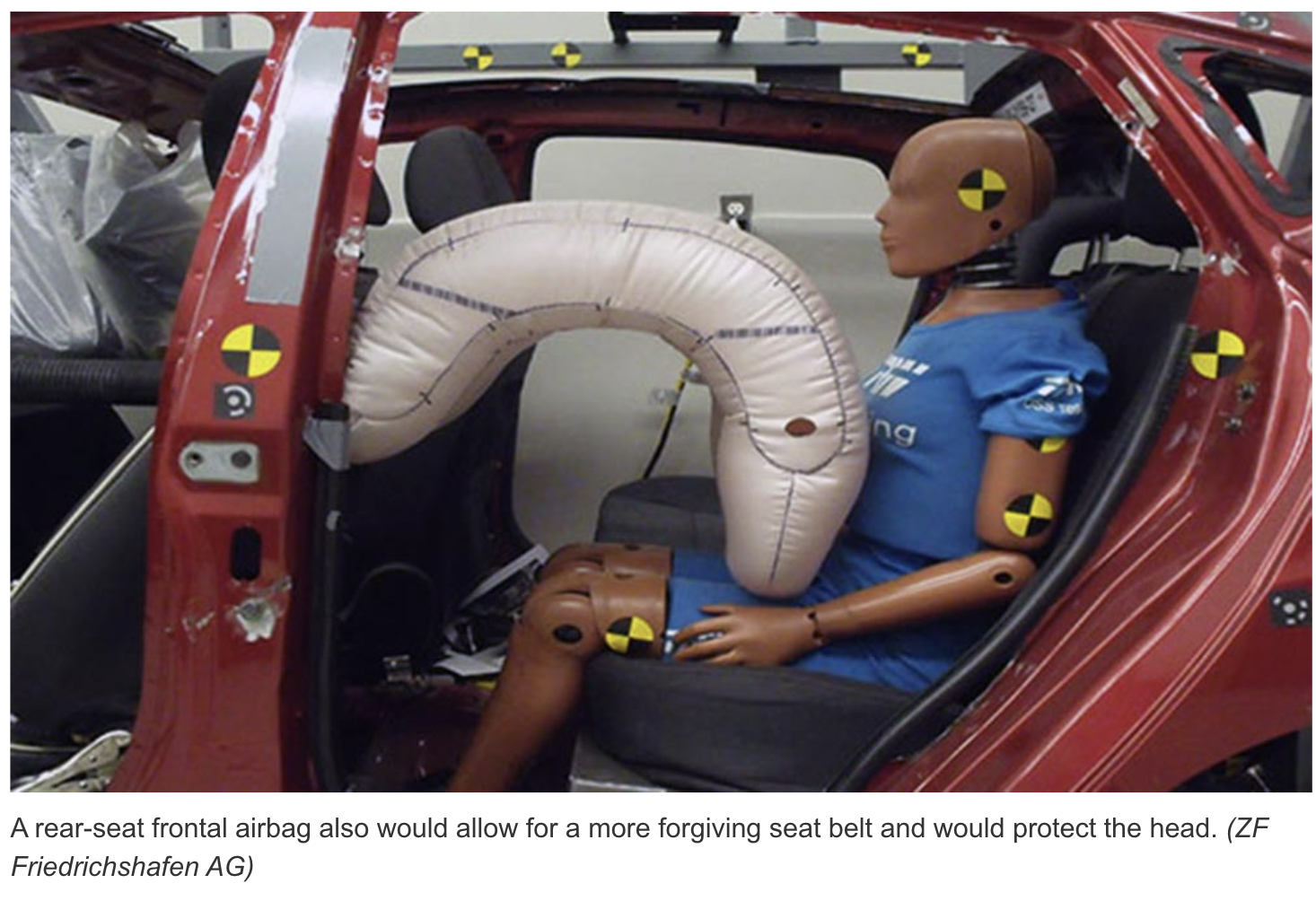

In the rear seat, side airbags protect passengers in a side crash, but there are no front airbags, and the seat belts generally lack crash tensioners and force limiters.

Although intruding structure is usually not an issue in the back seat during a frontal collision, crash forces can cause a back-seat passenger to collide with the vehicle interior. Seat belts can prevent that, but, as the new study shows, seat belts without force limiters can inflict chest injuries.

The study talks about how baby seats are safe, but that for people in the rear not in child seats, sometimes crash forces from their head hitting part of the car or from the seatbelt can cause serious injury.

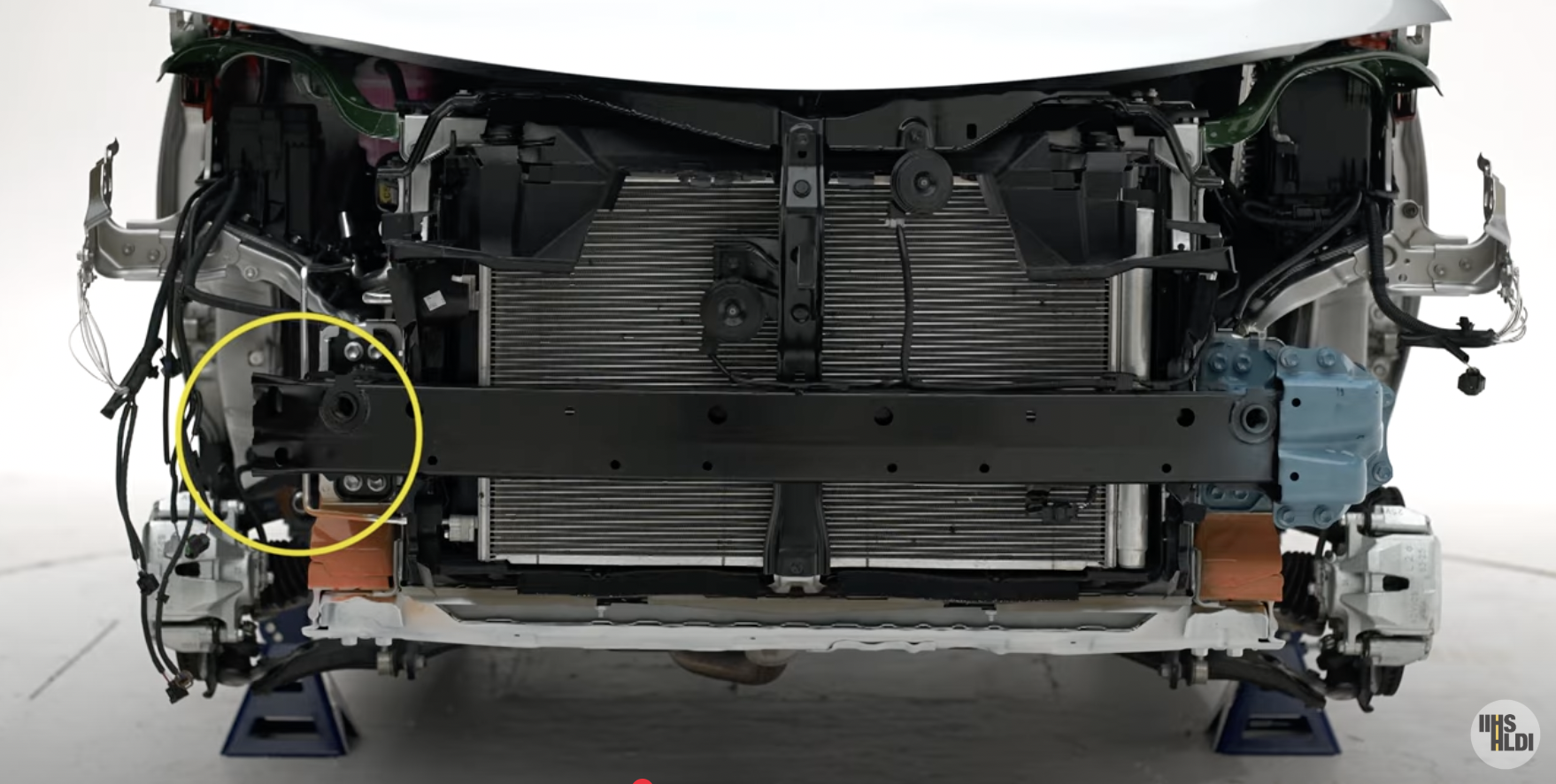

Will rear seats start to get airbags? Will we see more inflatable airbag-seatbelts in the rear? We’ll see. But for sure what we’ll see more of are crash tensioners and force limiters. “These two technologies combine to limit the forces to the chest during a frontal crash, which can prevent injuries,” per IIHS.

Some of those injuries can be a result of what’s called “submarining,” when the lap belt rides up into the abdominal:

Here’s a look at IIHS’s crash report for this new juggernaut of a test:

If big-dogs like the Toyota Rav4 and Honda CR-V are struggling, you know this is a tough one, and certainly now the big-dog in IIHS’s already challenging barrage of crash tests.

Source link