Mark SavageMusic correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMark Ronson is in trouble.

It’s summer 1998, and he’s hunched over the turntables at New York’s venerable VIP bar, Spy.

Ronson is there to DJ for Prince, the Purple pipsqueak of funk. It’s going well, until he pulls Michael Jackson’s Off The Wall from its sleeve, ready to drop the 1979 disco classic Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough.

Suddenly, someone’s tugging at his arm. It’s the rapper Q-Tip, and there’s an uncommon urgency to his voice as he shouts: “No! You can’t play that. Not in front of Prince!”

Remembering the star’s rivalry with Jackson in the 1980s, Ronson whips the record off the decks. But that leaves him with a problem.

“At this point there’s only 20 seconds left [of the previous song]. I pull another record out, but the tempos don’t match and I flub the mix.”

Ronson glances over to the VIP area, where Prince is holding court in a plush throne.

“And he’s glaring down at me like, ‘What is this train wreck?’

“It was slightly humiliating.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLuckily, train wrecks were a rarity.

Long before he was an Oscar-winning hitmaker for Lady Gaga and Amy Winehouse, Ronson was one of New York’s most in-demand DJs.

A nocturnal animal, he’d bait his prey with crates of vinyl, swooping in for the kill with a perfectly-timed drop of AC/DC’s Back In Black or Busta Rhymes’ Put Your Hands Where My Eyes Could See.

“I could walk into any room and, almost like the Terminator, scan the crowd and be like, ‘I know what the first three records are’,” he says.

That’s as close to boastfulness as Ronson gets. He’s so laid-back it’s almost comical, speaking in a perpetually sleepy drawl, like the Big Lebowski of music.

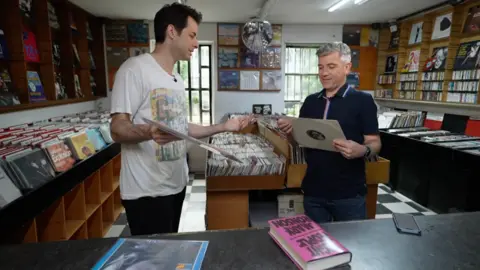

Mark Ronson

Mark RonsonWe meet in Notting Hill’s Music and Video Exchange – the shop that kick-started his record collection – and it’s only when he starts rifling through the racks that the 50-year-old comes to life.

“This one changed my life,” he says, pulling out a dog-eared copy of Pete Rock’s They Reminisce Over You.

“Oh, and here’s Salt-N-Pepa’s Shoop… Now, that’s my song!”

A similar enthusiasm permeates Ronson’s new memoir, Night People, which concentrates on the 1990s DJ career that saw him playing for everyone from Jay-Z to Mariah Carey.

“She had very specific songs she wanted to hear,” he recalls. “There was a great R&B record called Say I’m Your Number One, by Princess, that she’d always request.

“Eventually, I just knew to play it as soon as I saw her, to save her a trip to the booth.”

When he pitched the book, which ends long before his successes with Winehouse on Back To Black and Bruno Mars on Uptown Funk, “people were scratching their heads”, Ronson admits.

“They were like, ‘Oh right, so you want to write about the time before the thing we know you for?'”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut he stuck to his guns. The memoir is a heartfelt love letter to a bygone era, inspired by the death of his close friend and contemporary DJ Blu Jemz in 2018.

“I was just staring at all the records [we used to play] on my shelf, thinking about how each one was so evocative of a memory and a moment in time.

“It’s arguably the last time New York was the apex of hip-hop both creatively and commercially – A Tribe Called Quest, Wu-Tang, Biggie Smalls, Lil’ Kim, Busta Rhymes… all of it. And they were out in the clubs every night.”

Another figure who loomed over the scene was P Diddy, aka Sean Combs, who’s currently awaiting sentencing in New York after being found guilty on two counts of transportation for the purposes of prostitution.

Diddy gave Ronson one of his big breaks, hiring him to play at A-list events, including his 29th birthday party, after tipping the DJ with a $100 bill containing his phone number.

“It’s undeniable that the way he picked me for certain gigs elevated my star,” says Ronson, calling the accusations against Diddy “horrific”.

“I had no idea of anything like that going on,” he says, acknowledging the musician “wielded a tremendous amount of power and cachet” in New York.

“But in the five years I DJ’d for him, I doubt he spoke more than five sentences to me.

“He was mostly out there dancing and I knew if he was dancing, no-one was gonna yell at me.”

Mark Ronson

Mark RonsonAt the outset, Ronson wanted his book to capture the seediness of 90s club culture, where he’d play “night in, night out for $100” while “cokehead club owners shouted at me for not playing enough Madonna”.

As he wrote, another story also emerged.

Ronson was born in London to jewellery designer Ann Dexter-Jones and music publisher Laurence Ronson. Their house in St John’s Wood was a frequent haunt for actors and musicians, including Keith Moon and Robin Williams.

“My parents had crazy parties all the time,” he recalls. “Fifty or 60 slightly cracked people, smoking, drinking, having a great time.”

The aftermath was drastically different. In the book, he writes of “angry crescendos and heavy silences” from his parents’ bedroom, which instilled a “constant watchfulness that became instinct before I understood why”.

Later in life, DJing fulfilled a “need for control” that stemmed from that early instability.

“It wasn’t always the greatest way to grow up for a kid, and there was something about the DJ booth that was incredibly comforting.

“It’s like I’m an army of one. I make all the rules. It’s a refuge, in a way.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLearning to navigate delicate situations also helped Ronson’s career as a producer.

There’s an almost too-perfect example in Lady Gaga’s documentary Five Foot Two where, arriving for a recording session, the star crashes into Ronson’s car.

Mortified, she enters the studio in a garbled flurry of apologies. Ronson simply stretches out his arms for a conciliatory hug.

“If you have a problem, I wish you’d just say it to my face instead of my bumper,” he deadpans.

The situation is immediately defused.

Reminded of the scene, he says: “I remember working on that record [2016’s Joanne] pretty well, and Lady Gaga is probably one of the most chased, hounded, paparazzi-ed people you could imagine.

“Sometimes we’d slam the door and there’d be 20 people on the other side taking pictures. So my role is just to shut out the outside world [and] make the artist feel relaxed and comfortable at all times.

“Even when they’ve trashed your car.”

His unflappability also helped along Winehouse’s Back To Black, bringing focus to a feverish creative streak.

“I remember some of my friends saying, ‘Oh, you’re working with Amy? Good luck. She’s been working on this album for three years’,” he recalls.

“But when we got in the studio, she was such a fireball of inspiration. We demoed three or four songs, we wrote Back to Black, she wrote Rehab… All these things in five days. It’s a lot of incredible memories.”

Other songs took longer. Uptown Funk needed seven months. Dua Lipa’s Barbie anthem Dance The Night was rewritten “five or six times with different hooks”.

But those are stories for another time… and “maybe” a second volume of Ronson’s memoir.

Right now, though, I’ve lost him to the record store’s vinyl bins, picking out old favourites by the Stone Roses, Brand New Heavies and Cypress Hill – and prompting a moment of introspection.

“There are people who enjoy a night out and then there are night people,” he decides.

“I was definitely the latter… but I had no idea where it would take me.”

Source link