Chicago, Illinois

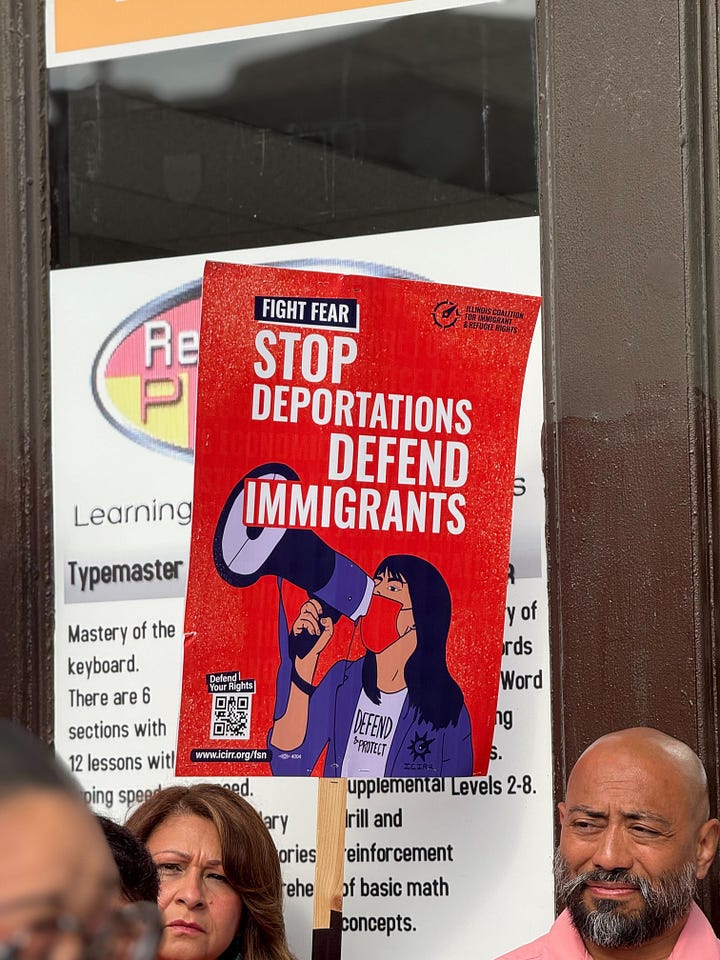

BEFORE DONALD TRUMP RETURNED to power, the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR) would receive roughly a hundred calls a month at its hotline for community members to report ICE sightings.

But as Trump publicly mused about declaring war on Chicago, things began to change: Call volume shot up to as many as five hundred in just one day.

That figure was just one of several startling revelations from a press conference ICIRR hosted along with the Illinois Legislative Latino Caucus and the Resurrection Project, a group that is connecting affected immigrant families with lawyers during the new crackdown. Local lawmakers at the press conference relayed that ICE activity was up in Archer Heights in southwest Chicago, as well as in west suburban Cicero and Berwyn, about twenty minutes outside downtown Chicago. On the first day of the Trump administration’s “Operation Midway Blitz” in the Chicago area, three people were arrested. DHS then touted thirteen more. The department called them the “worst of the worst”: criminals, rapists, and “violent thugs.”

The operation turned deadly Friday as an ICE agent shot and killed an immigrant just after he dropped off his kids at school. According to ICE, he resisted arrest, tried to flee the scene, and drove his car toward agents, one of whom was struck but then fatally shot the man.

Governor JB Pritzker said a full, factual accounting must come out, while activist leaders argued it was further evidence that the increasingly aggressive ICE tactics are making the community less safe.

This comes as Donald Trump’s clampdown on Chicago may not yet have taken its most heavy-handed form. For one thing, the military hasn’t stormed Chicago. The National Guard hasn’t been dispatched, and Trump seemingly announced on Friday that he was bypassing Chicago in favor of Memphis for his ‘Send the Military to Your Blue City’ Tour. But the federal government’s presence is very much felt here, like a chill from the lake. Much of it has settled over immigrant communities, where a pervasive fear has gripped the Latino and immigrant residents who are the lifeblood of many neighborhoods.

Illinois state representative Aarón Ortíz told me the operation is a dark shadow passing over the community, taking away regular, hardworking people.

“This is not law enforcement,” he said, “these are occupation tactics for TV and social media.”

“The community is being terrorized, that doesn’t mean it’s safer,” said local community activist Imelda Salazar with the Southwest Organizing Project, a progressive group that works across faith and racial lines. The White House, she added, was engaged in una guerra de miedo—“a war of fear.”

WHATEVER NAME ONE APPLIES to it, the fear began to kick in long before “Midway Blitz” even formally launched, as Trump for weeks framed Chicago as a failed city he would have to invade. The mood was conveyed to me through vivid anecdotes, like the one multiple organizers told me about Leodegario Martínez Barradas, a Latino flower vendor who worked at the intersection between South Archer Avenue and South Pulaski Road half an hour outside downtown. He was detained on Sunday and deported to Mexico on Tuesday, the Chicago Tribune reported. His presence—a fixture to passersby—was suddenly simply gone.

“He was a nice older man always trying to hustle,” Karina Martinez of the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council told me.

The fear is not just overtly palpable but present in subtle ways as well. School attendance is down; parents are afraid to pick up their children from school. Community events are being canceled, and people are afraid to attend the Mexican Independence day celebrations that started last week. Foot traffic has fallen off and business is following, making revenues plunge and putting businesses in the Mexican Main Street of Little Village in danger of closing.

Jennifer Aguilar, the executive director of the Little Village Chamber of Commerce, said that revenue is down 40 to 50 percent and that some businesses have closed while others are on the brink of closing. In Pilsen, another traditionally Latino area, Joe Gutierrez, a co-owner of margarita bar La Vaca—which has been in the area for generations—said business is also down 40 percent.

Local activists and Democrats believe that while ICE has held off, for now, on massive sweeps, it is conducting roving detention raids in scattershot fashion across the city. Andrew Herrera, who handles communications for the Resurrection Project’s immigration arm, said the upshot may be just what the administration really wants: for the city to be overtaken by an atmosphere of pervasive fear.

“If you can’t get the [arrest] numbers, you can take over the media cycle, turn on the panic, and freak people out,” he told me after the press conference.

Lori Lightfoot—who, during her tenure as mayor, dealt with a migrant crisis brought about by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott sending busloads of immigrants from his state to blue cities like hers—said the “fear” and “anxiousness” in immigrant-heavy areas is now ubiquitous.

Undocumented people, she explained, “are just staying home.” And it was having downstream effects: “They’re not going out to events,” she told me. “At health care clinics, people are canceling appointments. There’s a lot of fear of the unknown.” “There’s not a lot of ICE presence in the city right now . . . but the psychological warfare is real, and it’s having an impact.”

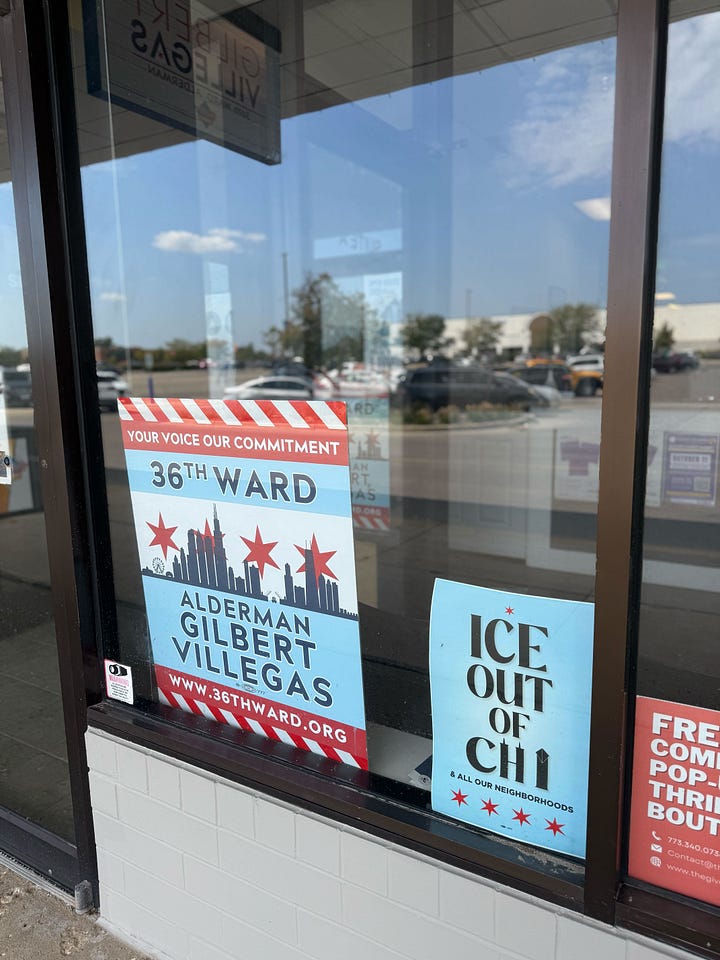

GIL VILLEGAS, A FORMER U.S. MARINE, is the 36th Ward Alderman. His district in Belmont Cragin is 79 percent Latino. But that may be undercounting it. Villegas’s chief of staff calls it the fastest-growing Latino neighborhood in Chicago, with people migrating there from Humboldt Park, Pilsen, and elsewhere. Like many Americans, they really love their neighborhood. They love being Latino, too.

As I headed into the area, I saw a Puerto Rican flag stationed next to the front door of a home. Cars with Mexican flags were also a common sight. I saw these as a reminder that Mexican Independence Day was coming, but locals said some of them were intended as a modest act of protest against the Trump administration, too.

I went to Belmont Cragin, forty-five minutes outside downtown, so I could see what is really happening in a neighborhood ICE would prioritize if it were planning major raids.

What I discovered is that the culture of fear is often experienced through things said in hushed or frantic tones. There is a steady stream of reports of ICE sightings, each of which then needs to be tracked down and verified, sometimes by Villegas’s office and often also by community groups. An Instagram page in the area has grown popular for posting all the tips the account owner receives about ICE operations. But some of the posts end up being dated photos. People are sent scrambling by them nonetheless.

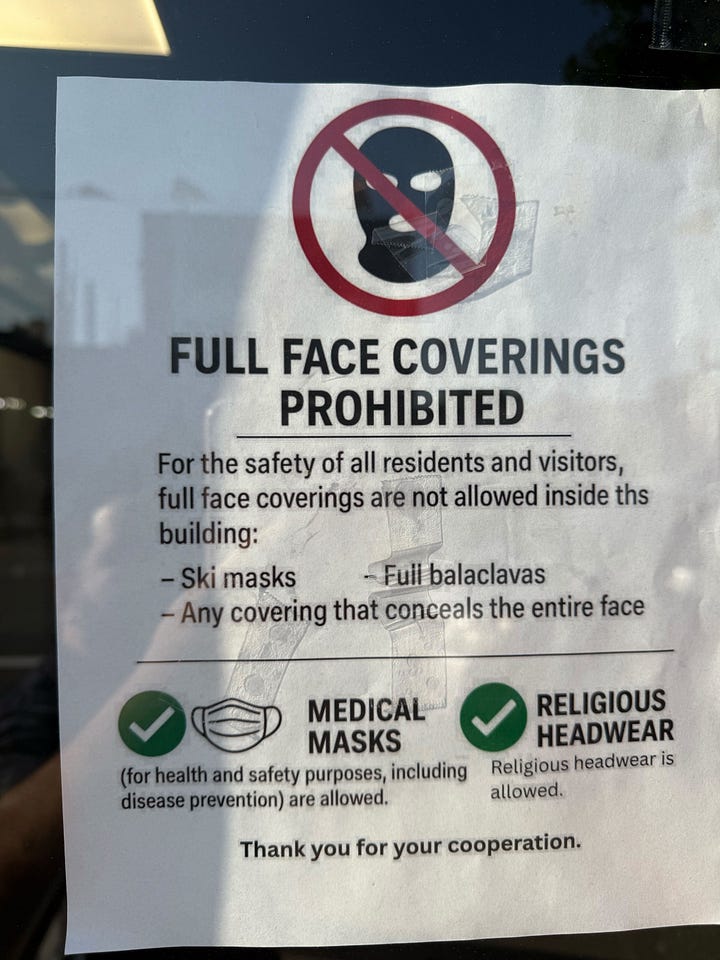

All across Belmont Cragin, school attendance is down, and parents and residents aren’t showing up for community events. Doors here are locked, even at Mexican restaurants, barring anyone from coming in unless they are cleared. There’s something unsettling about going to a place for food and community and finding the doors locked. One Mexican restaurant owner told me it’s a “temporary” measure, “until things calm down.”

When I went to the school building that houses a community enrichment program for parents (aptly called Parent University), a student there unlocked the door for me. I met Erika Amaya, in her fourth year as director of the community program. She said 80 percent of the parents who use their resources are undocumented. During this first week of programming, twenty-two parents registered for its mental health services, but only thirteen showed up. A similar diabetes workshop saw only half of its expected attendance.

In Villegas’s office, I spoke with Mari, an undocumented mother of two U.S. citizen kids, who said the fear in the Chicago area was persistent. As we spoke, her 11-year-old son played nearby, listening. I asked what the plan was if she were to be taken. She said a family member would come up from Miami to care for her son. She tried to voice positivity, but it was not hard to see how much the uncertainty of it all weighed on her.

Sitting next to us was Vanessa Valentin, Villegas’s chief of staff, who had helped organize the interview.

“If ICE came and got all the undocumented out of Belmont Cragin,” Valentin said, “we would lose our community.”

Source link