So it was the early astronauts that kind of drove the desire to take cameras themselves, but they were quite basic. Wally Schirra (Mercury-Atlas 8) then took the first Hasselblad. He wanted medium format, better quality, but really, the photographs from Mercury aren’t as stunning as Gemini. It’s partly the windows and the way they took the photos, and they’d had little experience. Also, preservation clearly wasn’t high up on the agenda in Mercury, because the original film is evidently in a pretty bad state. The first American in space is an incredibly important moment in history. But every single frame of the original film of Alan Shepard’s flight was scribbled over with felt pen, it’s torn, and it’s fixed with like a piece of sticky tape. But it’s a reminder that these weren’t taken for their aesthetic quality. They weren’t taken for posterity. You know, they were technical information. The US was trying to catch up with the Soviets. Preservation wasn’t high up on the agenda.

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

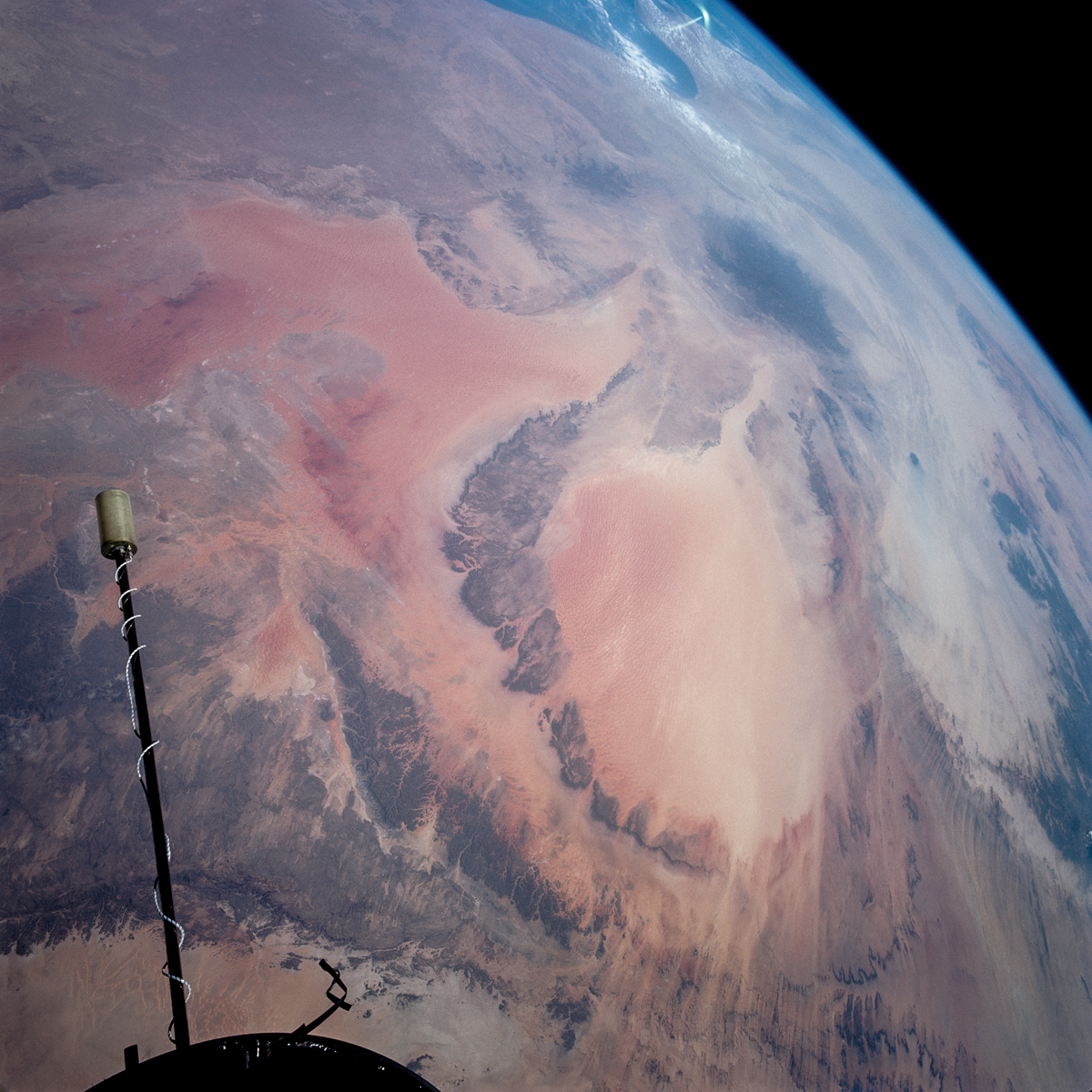

This is not some distant planet seen in a sci-fi movie, it’s our Earth, in real life, as we explored space in the 1960s. The Sahara desert, photographed from Gemini 11, September 14, 1966. As we stand at the threshold of a new space age, heading back to the Moon, onward to Mars and beyond, the photographs taken during Mercury and Gemini will forever symbolize and document the beginning of humankind’s expansion out into the cosmos.

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

Gemini took not only some of the first, but still some of the finest photographs of Earth ever captured on film – partly due to the high altitudes they flew to. Gemini 11’s Earth orbit altitude record held for 58 years until last year’s Polaris Dawn mission. Reflected in the window, Richard Gordon’s hand can be seen as he releases the shutter of his Hasselblad camera to capture the moment of apogee, over eastern Australia on September 14, 1966.

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

The rudimentary-looking Gemini spacecraft, Earth, and the unfiltered, bright, white sunlight captured at the start of Gene Cernan’s “spacewalk from hell” on Gemini 9A, June 5, 1966. Effectively blinded, exhausted, overheating, and losing communications with his Command Pilot, Cernan was fortunate to make it back inside the spacecraft alive.

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

Gemini took not only some of the first, but still some of the finest photographs of Earth ever captured on film – partly due to the high altitudes they flew to. Gemini 11’s Earth orbit altitude record held for 58 years until last year’s Polaris Dawn mission. Reflected in the window, Richard Gordon’s hand can be seen as he releases the shutter of his Hasselblad camera to capture the moment of apogee, over eastern Australia on September 14, 1966.

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

The rudimentary-looking Gemini spacecraft, Earth, and the unfiltered, bright, white sunlight captured at the start of Gene Cernan’s “spacewalk from hell” on Gemini 9A, June 5, 1966. Effectively blinded, exhausted, overheating, and losing communications with his Command Pilot, Cernan was fortunate to make it back inside the spacecraft alive.

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

NASA / ASU / Andy Saunders

Ars: I want to understand your process. How many photos did you consider for this book?

Saunders: With Apollo, they took about 35,000 photographs. With Mercury and Gemini, there were about 5,000. Which I was quite relieved about. So yeah, I went through all 5,000 they took. I’m not sure how much 16 millimeter film in terms of time, because it was at various frame rates, but a lot of 16 millimeter film. So I went through every frame of film that was captured from launch to splashdown on every mission.

Ars: Out of that material, how much did you end up processing?

Saunders: What I would first do is have a quick look, particularly if there’s apparently nothing in them, because a lot of them are very underexposed. But with digital processing, like I did with the cover of the Apollo book, we can pull out stuff that you actually can’t see in the raw file. So it’s always worth taking a look. So do a very quick edit, and then if it’s not of interest, it’s discarded. Or it might be that clearly an important moment was happening, even if it’s not a particularly stunning photograph, I would save that one. So I was probably down from 5,000 to maybe 800, and then do a better edit on it.

Source link