Astronomers have spotted a cosmic explosion of high-energy gamma-rays unlike any ever seen before. The gamma-ray burst (GRB) designated GRB 250702B set itself apart from other explosive bursts of gamma-rays by exploding several times in one day.

That’s something difficult to explain, given GRBs are thought to arise from the catastrophic deaths of massive stars, with no known scenario currently accounting for repeated blasts over a full day. Co-lead researcher and University College Dublin astronomer, Antonio Martin-Carrillo, said in a statement that this GRB is “unlike any other seen in 50 years of GRB observations.“

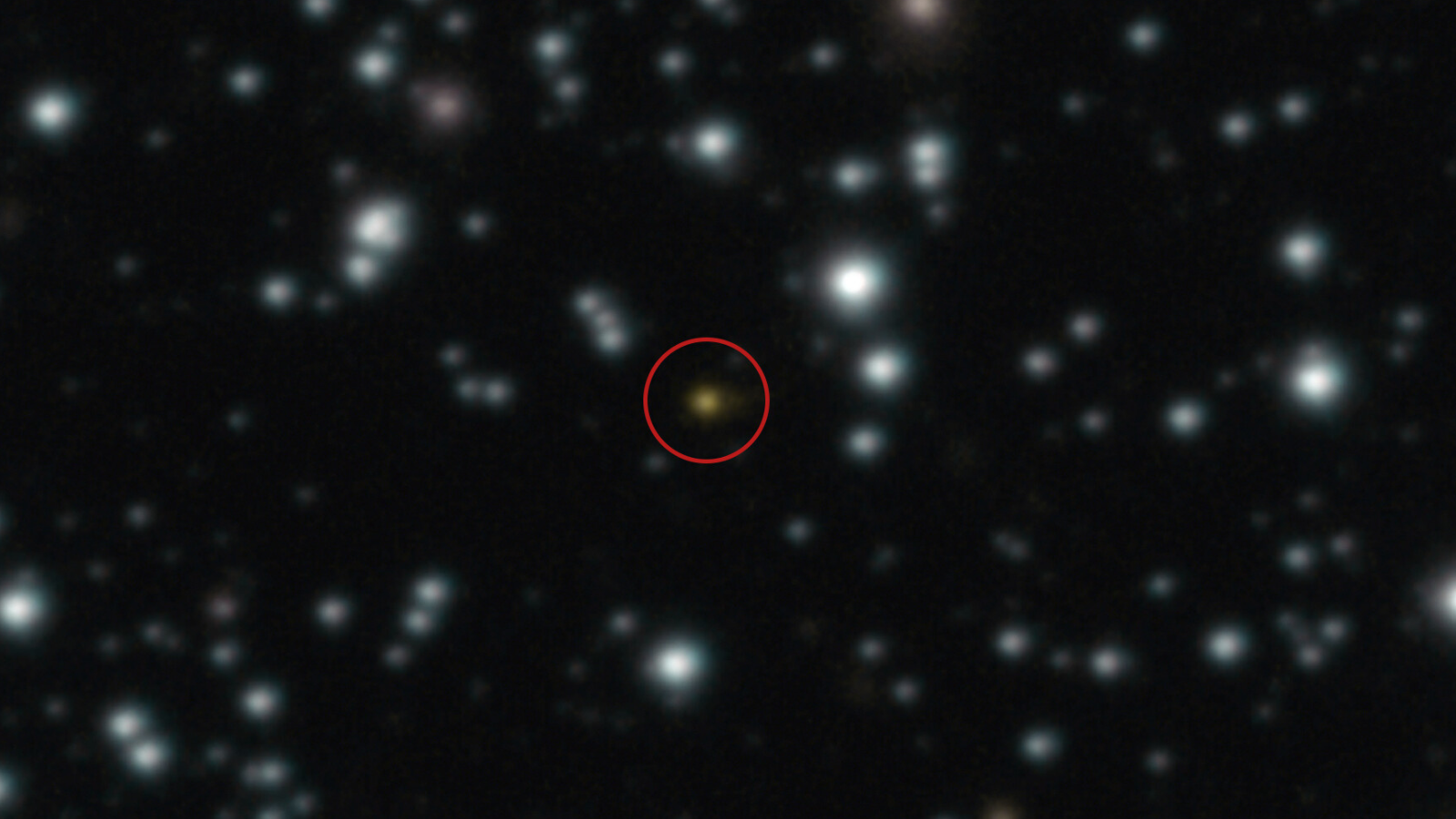

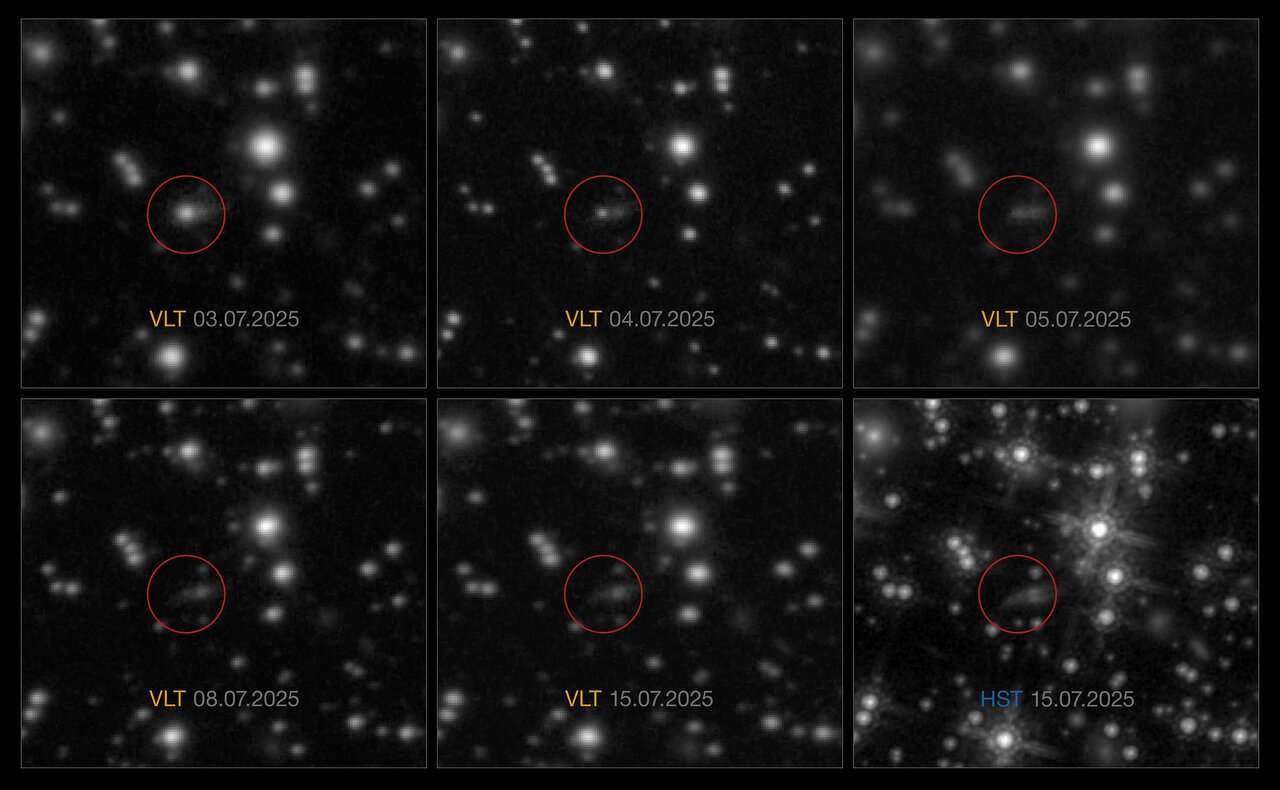

GRB 250702B was initially detected by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope on July 2, 2025, but its location was uncertain. The following day, GRB 250702B was investigated by the Very Large Telescope (VLT), which used its HAWK-I infrared camera to pinpoint the source of this GRB outside the Milky Way. This was later confirmed by the Hubble Space Telescope.

GRBs are believed to occur either when massive stars reach the end of their lives and undergo gravitational collapse to become black holes or neutron stars, or when an unfortunate star wanders too close to a black hole and is shredded in a so-called “tidal disruption event.”

This leads to what are currently thought to be the most energetic explosions in the universe, putting out as much energy in a period ranging from milliseconds to minutes as the sun will radiate in around 10 billion years.

GRB 250702B, on the other hand, lasted around a day. That is 100 to 1,000 times longer than most GRBs, according to co-team leader and Radboud University researcher Andrew Levan.

“More importantly, gamma-ray bursts never repeat since the event that produces them is catastrophic,” Martin-Carrillo added.

When Fermi initially saw GRB 250702B on July 2, the space telescope saw it burst three times over a few hours. Then, an examination of data from the Einstein Probe X-ray space telescope revealed that the same source had erupted a day prior. This makes GRB 250702B a long-period repeating GRB like nothing astronomers have previously observed. Its nature remains a mystery.

“If this is a massive star, it is a collapse unlike anything we have ever witnessed before,” Levan said.

Fermi and the Einstein Probe could not pinpoint the source of GRB 250702B, with the explosion appearing to have come from the plane of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. To confirm or refute this, the team turned to the VLT, one of the world’s most advanced optical telescopes located at the Paranal Observatory in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile.

“Before these observations, the general feeling in the community was that this GRB must have originated from within our galaxy,” Levan said. “The VLT fundamentally changed that paradigm.”

Observations made with the HAWK-I camera showed that GRB 250702B actually erupted beyond the limits of the Milky Way, in another galaxy. This was then confirmed by Hubble.

The exact distance to the source of GRB 250702B isn’t certain yet, but the team thinks that the size and brightness of its home galaxy indicate it is located billions of light-years away.

“What we found was considerably more exciting: the fact that this object is extragalactic means that it is considerably more powerful,” Martin-Carrillo said.

Further investigation of GRB 250702B will be needed to both more accurately pinpoint its location and to determine what caused this long-lasting repeating blast of gamma-rays.

One explanation would be a massive star collapsing onto itself, releasing vast amounts of energy. This should have created a GRB lasting mere seconds, however. Alternatively, a star being ripped apart in TDE could produce a day-long GRB, but this scenario fails to replicate other properties of the GRB 250702B, an explosion that would require a very unusual star being destroyed by an even stranger black hole.

The team is currently monitoring the site of this explosion with the VLT and the James Webb Space Telescope, hoping to catch a glimpse of its aftermath to better understand its nature.

“We are still not sure what produced this, but with this research, we have made a huge step forward towards understanding this extremely unusual and exciting object,” Martin-Carrillo concluded.

The team’s research was published on Aug. 29 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Source link