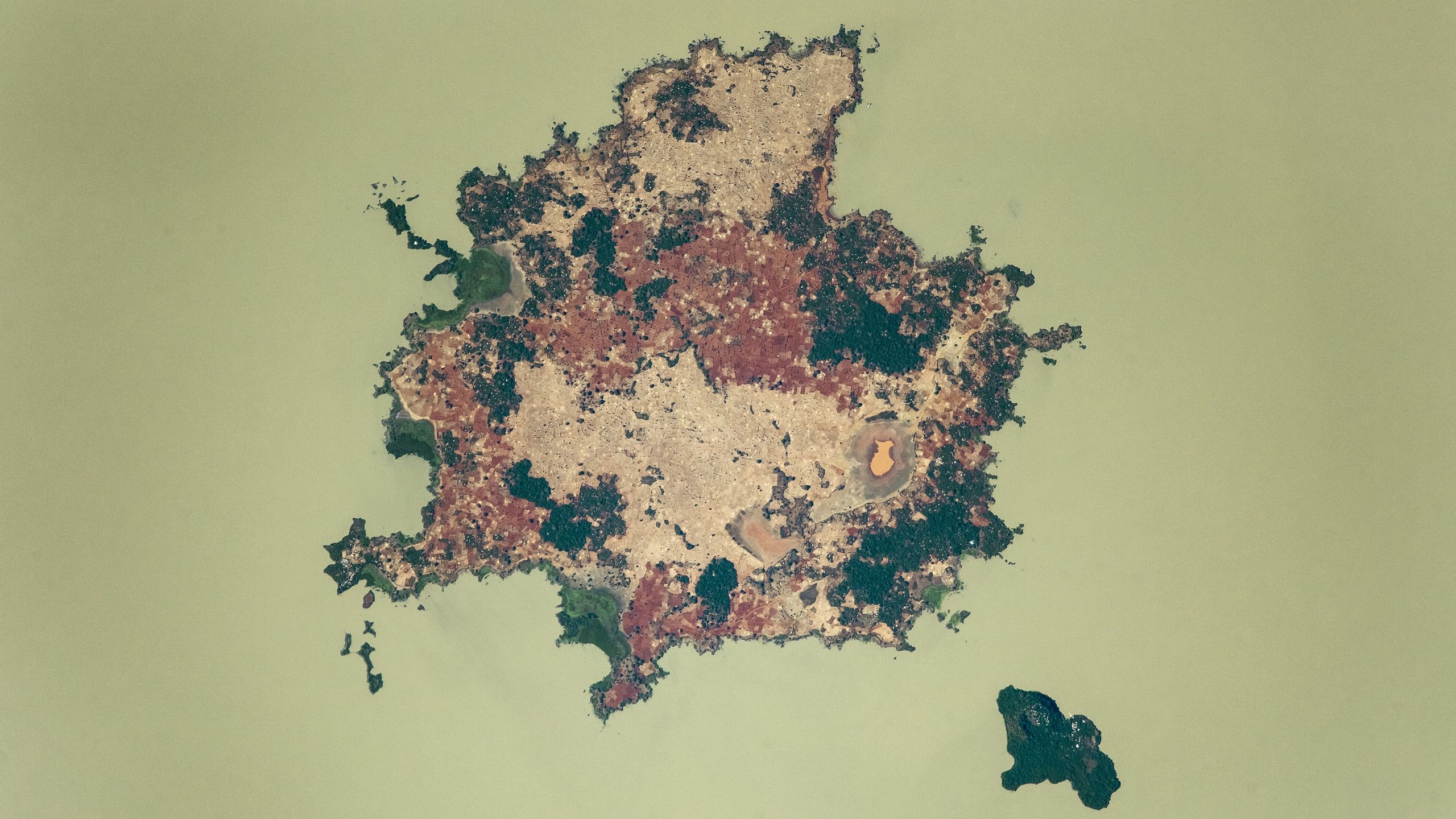

The appearance of strange ‘islands’ bristling with reeds on the drying playa of Utah’s Great Salt Lake may finally have an explanation.

A vast, natural network of underground plumbing emerges from the depths, piping in fresh water that feeds mounds where plant life can thrive, according to extensive surveys conducted by scientists over several years.

This opens a new window into the lake’s vast, complicated ecosystem that may help scientists learn how it works and how it might be preserved.

Related: Volcanic Activity Beneath Yellowstone’s Massive Caldera Could Be on The Move

“The last thing we wanted to do is for this to be characterized as a water resource we should be tapping,” says geologist Bill Johnson of The University of Utah. “It’s much more fragile than that, and we need to understand it better.”

The Great Salt Lake is one of the most ecologically important bodies of water in the US. Worried about its stability, scientists have been recording the lake’s slow decline in water levels since the 1980s. In 2022, the levels reached a record low.

As the water level falls, the salinity of the lake increases, disturbing the delicate balance on which life in the lake relies.

There’s a downside for humans, too. The drying lake exposes and dries the sediment that was on the lakebed. This fine silt turns to dust that affects nearby human towns and cities when the wind kicks up.

For these reasons, it’s important to understand where the lake’s water comes from. Most of it comes from rainfall and surface runoff, but the contribution from groundwater beneath the lake is unclear.

Johnson and his colleagues have been using nested piezometers, seepage meters, salinity profiles, resistivity surveys, permeability measurements, and environmental tracer data to monitor the lake, but in February 2025, they upped the ante. They recruited a company called Expert Geophysics to perform aerial electromagnetic surveys over Farmington Bay.

These surveys measure the magnetic fields over a given area. Scientists can then use these data to generate a 3D reconstruction of what’s under the ground. Coupled with data collected from the surface, a complex picture of an underground freshwater reservoir is emerging.

On the mounds themselves, the water is freshest at the center, becoming saltier and saltier the farther from the center you go. The new measurements suggest that the reservoir could extend in sediments more than 3,000 meters (10,000 feet) below the surface.

“We don’t know if it’s freshwater that deep, but it is certainly going to be fresh a long way down, and it could be fresh all the way down,” Johnson says.

“The last thing I want to do is get this hyped as a water resource, but it’s very clear, and it’s under pressure. And in my mind, it could help mitigate any dust generation on the exposed playa.”

The team’s findings were presented in July at the 2025 Goldschmidt conference.

Source link