A newly released study in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research has confirmed the first official sightings of Bootanomyia dorsalis—a European parasitic wasp—in both the eastern and western United States, raising concerns about ecological balance and species disruption. Researchers have confirmed that Bootanomyia dorsalis, a wasp species previously unseen in North America, is now causing alarm among scientists for its potential to disrupt local biodiversity and insect populations tied to native oak trees.

The wasp, which targets other parasitic insects known as oak gall wasps, has been quietly spreading through ecosystems with little fanfare. But new genetic evidence suggests it’s already more established than anyone expected—and its arrival could ripple through food webs in unpredictable ways.

What is Bootanomyia dorsalis and Why It Matters

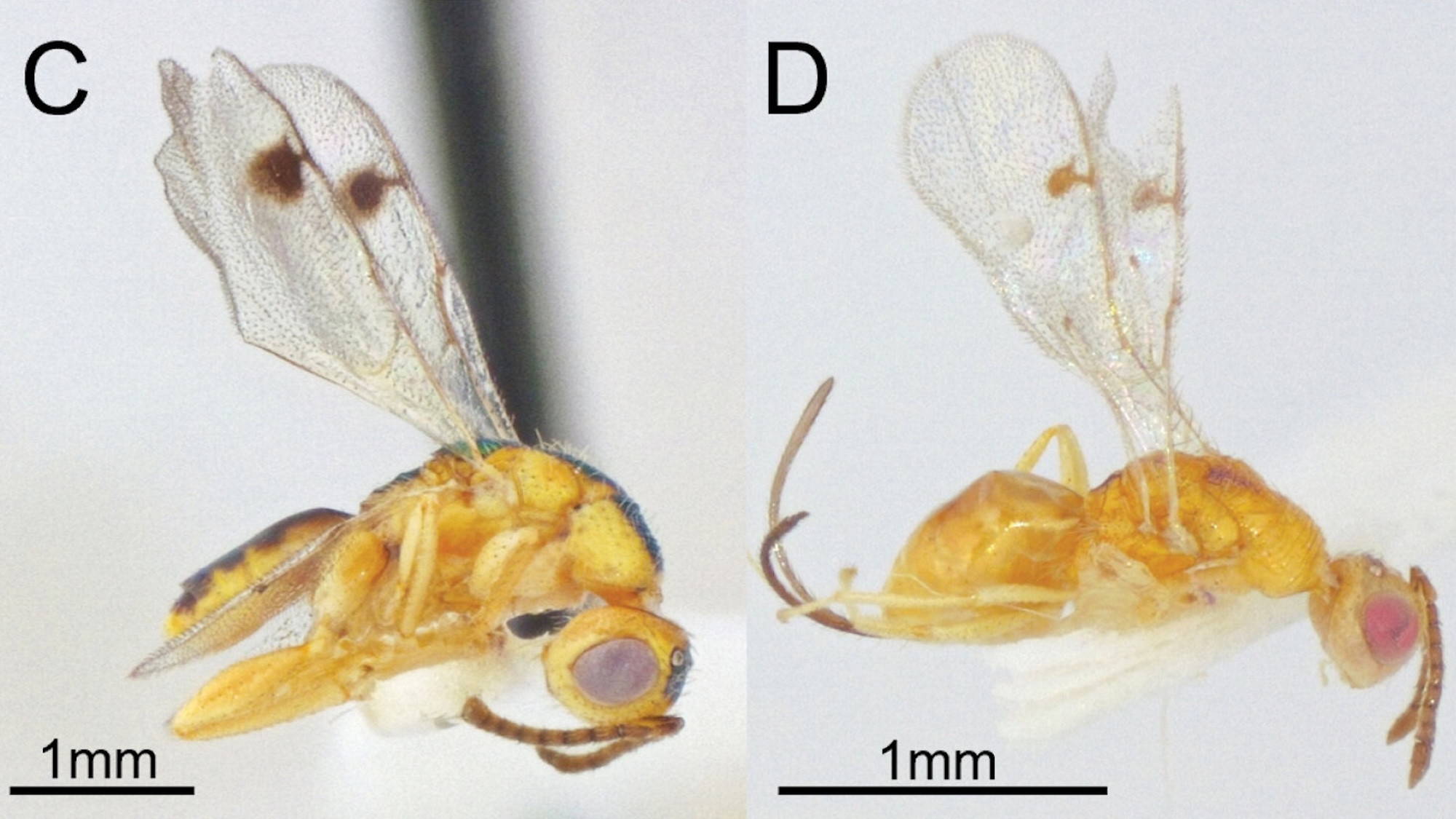

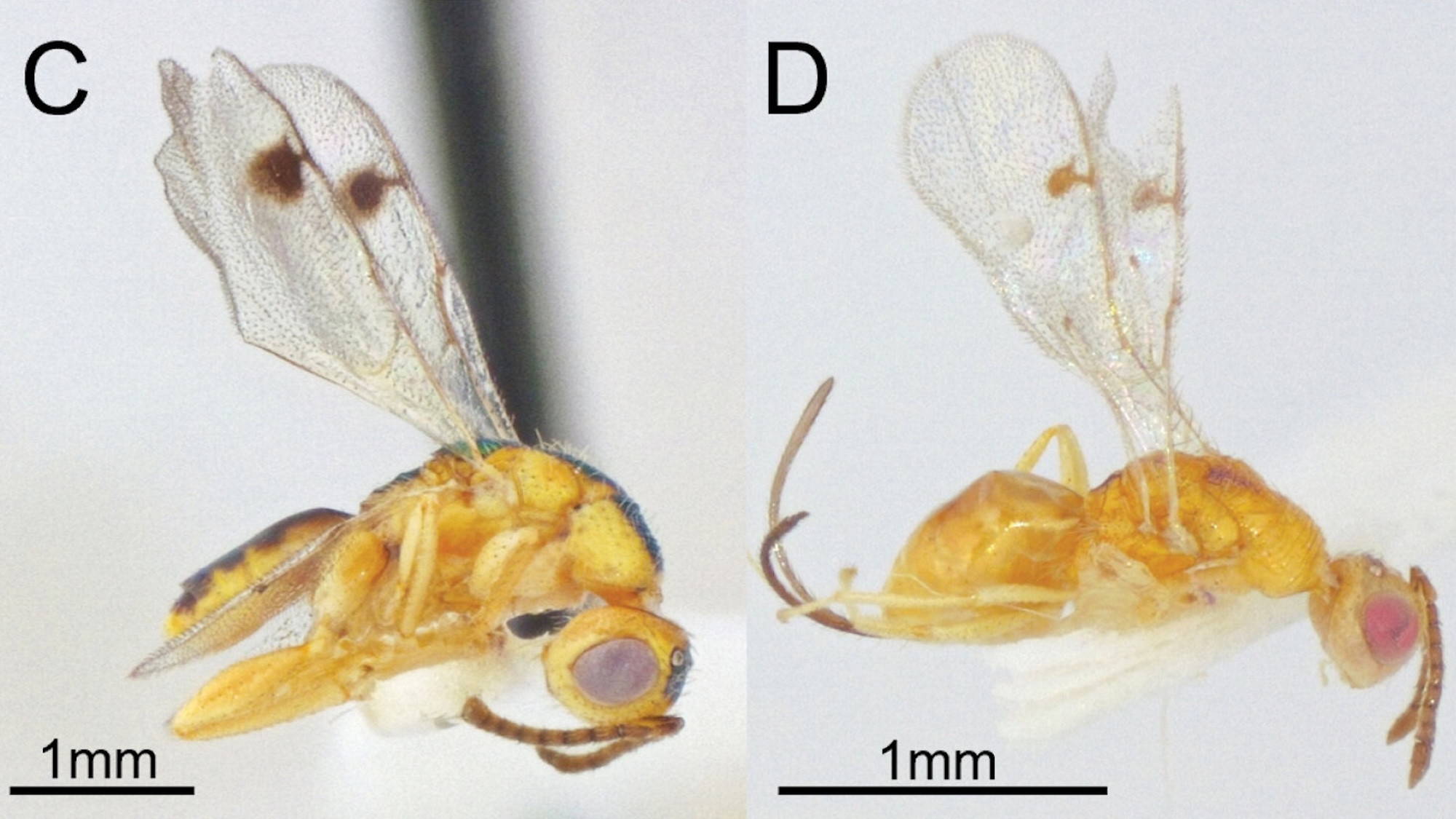

Unlike invasive species with high public visibility—think lanternflies or murder hornets—B. dorsalis is less dramatic in appearance, measuring just a few millimeters long. But its ecological impact could be significant. Native to Europe, B. dorsalis is a parasitoid, meaning it lays eggs inside other insects’ nests, killing the host larvae as its own offspring develop.

Its primary targets in the US appear to be oak gall wasps, a group of insects that use oak tree tissue to form protective growths—called galls—where they reproduce. The US is home to around 800 species of oak gall wasps, many of which are endemic. These insects may not be charismatic, but they form an important part of the ecosystem: their galls provide habitat and food for other insects, birds, and small animals.

According to Kirsten Prior, a biological sciences professor at Binghamton University and co-author of the study, parasitic wasps like B. dorsalis are “extremely important in ecological systems,” often serving as natural pest control agents. But the introduction of a non-native parasitic species like this one risks throwing those dynamics off balance.

Genetic Clues Reveal Two Separate Invasions

The research team discovered the wasp on both coasts of the US—specifically in New York and across several sites along the Pacific Coast. At first, it was unclear whether the same species had colonized both regions. But through genetic sequencing of mitochondrial DNA (specifically the Cytochrome Oxidase Subunit I gene), the researchers found something unexpected: the East and West Coast populations were genetically distinct.

That finding points to at least two separate introductions of B. dorsalis into North America. The East Coast wasps appear genetically similar to populations found in Portugal, Italy, and Iran. In contrast, the West Coast wasps are closely linked to individuals from Spain, Hungary, and also Iran. The higher genetic diversity observed on the East Coast suggests that these populations may have been introduced earlier or through multiple independent events.

The researchers speculate that the species might have first arrived as early as the 1600s, when European colonists brought over non-native oak species. But a more plausible theory is that modern global air travel introduced the insect more recently. Adult B. dorsalis can live up to 27 days, giving them ample time to survive transcontinental flights tucked inside cargo, luggage, or nursery plants.

How These Wasps Could Alter US Ecosystems

The presence of B. dorsalis raises immediate concerns among ecologists. While parasitic wasps generally play a useful role in natural insect control, the introduction of a foreign species threatens to destabilize native parasite-host networks. In this case, B. dorsalis competes with—and preys on—native parasitic wasps that have co-evolved with oak gall wasps over millions of years.

By targeting the larvae of oak gall-forming wasps, B. dorsalis removes a key component in oak forest food webs. These galls feed not only other insects but also woodpeckers, chickadees, and a wide array of forest-dwelling creatures. A collapse in gall wasp populations could result in a cascading decline in dependent species.

The exact ecological impact remains unclear, but Kirsten Prior warns that B. dorsalis has already demonstrated the ability to “parasitize multiple oak gall wasp species,” suggesting a high potential for widespread disruption.

Source link