Hurricane Katrina was a terrifying experience for more than a million people affected across the Gulf Coast region. Nearly 1,400 people died, most of them in New Orleans — and 20 years later, some communities are still struggling to recover.

The National Hurricane Center says the costliest hurricane in U.S. history — more than $201 billion based on the 2024 Consumer Price Index adjusted cost — caused widespread flood damage across Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.

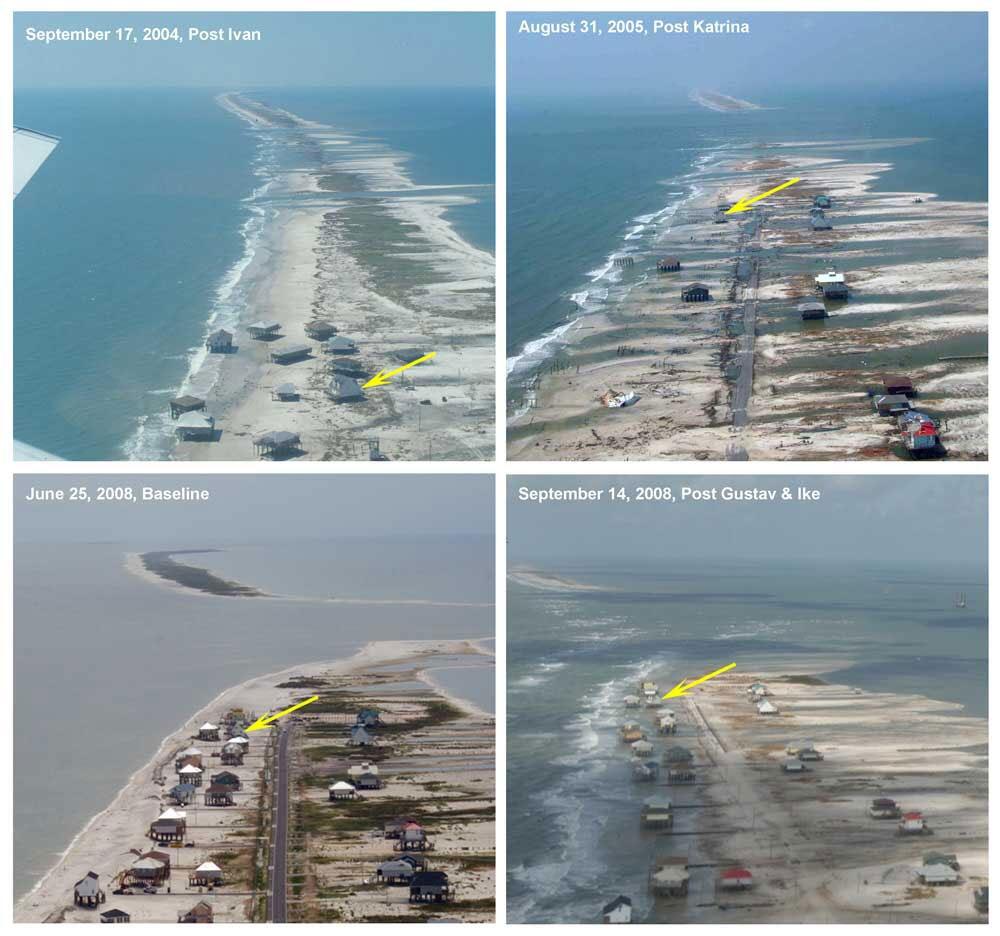

On Dauphin Island, Alabama, the barrier island town’s west end beach was severed during Katrina. A 1.5 mile-wide gap was left behind. More than 300 homes were destroyed on the island, and for many of those homes, the land on which they stood was permanently washed away.

Since Hurricane Katrina made landfall on Aug. 29, 2005, Dauphin Island has been shrinking and moving even more from additional storms and sea level rise. The island is now facing a dire existential crisis.

Mayor Jeff Collier never imagined storms, big or small, would batter the island so hard. Some residents are still paying property taxes on lots that are now under Gulf waters — vacationers frequently swimming over top of them.

“This area here is where most of those underwater lots are,” Collier said as he took a CBS News crew on a tour of Dauphin Island. “There are probably 50 lots in this stretch of the island.”

Some residents’ homes are sitting in perilous positions, their pilings now situated well into the Gulf. The homes are still technically livable — vacationers even renting them out this summer — but Collier says it’s only a matter of time before another storm wipes out more.

Over the last 20 years, the town has rebuilt some of its white sand beaches. Last year, on the island’s east end, the town was able to use Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill settlement money on a beach erosion project to push Gulf waters back about 350 to 400 feet, according to the mayor.

But on a barrier island like Dauphin, constant maintenance is critical. Jillian Fairbanks visits the island frequently and has seen the erosion first-hand over time.

“Just about a year later, I can already tell that the sand has eroded, I’d say 30 meters or so at least,” Fairbanks said. “It was still a shock to see that happen already in one year.”

Her parents have lived there for 13 years. She says they’ve advocated for beach restoration projects for years to protect the town.

“It’s more calm, laid back, peaceful,” Fairbanks said. “I’ll come here as long as it’s here.”

USGS

It will take millions of dollars from several grant sources to preserve what’s left, and Collier says that’s the biggest challenge.

Dauphin Island is planning to use more oil spill settlement money to help pay for another beach restoration project for the island’s west end, which will cost $60 million. The mayor is still pursuing additional funding sources to make the project possible.

He’s also utilizing help from an Environmental Protection Agency grant to upgrade the town’s stormwater runoff systems to help mitigate street flooding during storms, even low-grade ones. As of April, Collier says the town had already spent more than $420,000 on the $1.2 million project.

Because these projects need continuous upkeep and oversight, Collier sought help from a special FEMA program. He said a grant for a $250,000 project would help the town hire an engineering and design firm to create a specialized disaster mitigation plan.

The Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities grant, or BRIC, includes investments in state planning and capacity building, such as $2 million in Alabama to support statewide building code implementation costs, according to Derrick Hiebert, who oversaw the program.

He served as assistant administrator for the Hazard Mitigation Directorate at FEMA for the last two years.

“We selected over 1,900 projects. FEMA selected over 1,900 projects worth nearly $5 billion,” Hiebert said. “This included $150 million over three grants to improve three canal basins in South Florida that are plagued by flooding.”

He added the BRIC program was also funding a massive flooding mitigation project in Washington state.

“The North Shore Levy — $80 million in federal funding to a community that has suffered significant economic disruption in recent years,” he said. “It was going to protect 3,100 homes and businesses, removing them from the FEMA-designated floodplain and reducing risk in that community.”

Hiebert said it also helped some other western communities with wildfire mitigation efforts and was first established with bipartisan support.

“It was established during the first Trump administration, after the passage of the Disaster Recovery Reform Act, and it helped solve several long-standing challenges with local governments,” Hiebert said.

Against Hiebert’s wishes, the Trump administration’s FEMA canceled the program in April, calling it “wasteful and ineffective.” In another announcement, the agency said BRIC resulted in a “lack of concrete results.”

Hiebert said he supports any administration’s ability to “evolve and adapt” and he doesn’t see changes to FEMA as a bad thing, but he believes the cancellation of such projects is “devastating” to the places that need them.

“If the administration wants to change FEMA, or change the BRIC program to something different that looks a little different, that’s the prerogative. That’s good,” he said. “These communities that were expecting these funds, that were counting on these funds for these real large-scale infrastructure projects, what hurts me the most is to know that some of them, or many of them, may not get built, and that these risks … don’t have another place to turn to address these risks.”

Hiebert said he quit his position in June, two months after the program was scrapped. A group of 20 states last month sued the Trump administration, seeking to block what they say was an illegal termination of BRIC.

In response to the lawsuit, a FEMA spokesperson told CBS News that resiliency is a priority for the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees FEMA. “But over the last four years the Biden Administration used the BRIC program as a piggy bank for its green new deal agenda,” the spokesperson said.

FEMA data shows the cut impacted nearly 700 projects at a cost of $3.6 billion. A CBS News investigation found that the recent BRIC funding cuts have disproportionately affected counties that supported Mr. Trump in the 2024 election. The elimination of the BRIC program also especially deprives vulnerable communities across the Southeast, the CBS News data analysis found.

Earlier this month, a federal judge temporarily blocked the BRIC funding reallocation, arguing the transfer could lead to “irreparable harm” to flood-prone areas. Meanwhile, Collier says he has not heard any word from the federal government about next steps.

“We’re kind of in a limbo situation right now waiting to see what comes out of that,” Collier said.

CBS News reached out to FEMA for a comment, but has not received a response.

Collier said if it comes down to it, he will pursue paying for the hazard mitigation plan out of pocket.

“Of course, it’s nicer when you have grant funds to work with, but at the same time, this is such a critically important thing that we need … If we can’t get the funding elsewhere, you know, we just have to just deal with it ourselves,” Collier said. “So, one way or the other, we’re going to get our plan in place.”

Time is something Dauphin Island cannot afford. Even without a major hurricane, the beach is expected to continue washing away.

Asked what keeps him up at night, Collier said, “just the fact that we know additional hurricanes will eventually hit this area … knowing that there’s a clock ticking, that we only have a certain length of time in order to make differences and changes on the island before the next one hits.”

Source link