Cancer drugs that have been used for two decades were retooled until they were able to eliminate aggressive tumors in a “remarkable” clinical trial.

Two of the patients—one with the deadliest form of skin cancer called melanoma and another with breast cancer—were told their tumors disappeared completely.

Scientists at Rockefeller University in New York engineered an upgrade to an antibody that improved a class of drugs—called CD40 agonist antibodies—which have struggled to make good on their early promise, but showed great potential.

While effectively activating the immune system to kill cancer cells in animal models, the drugs had only “limited” impact on humans, while also triggering dangerous adverse reactions.

So, five years ago, the team at the New York university engineered an enhanced CD40 agonist antibody so that it improved its efficiency and limited any serious side effects for mice, with the next step being a clinical trial with cancer patients.

The results from the phase 1 clinical trial of the drug, dubbed 2141-V11, showed that six out of 12 cancer patients saw their tumors shrink, including two that saw them disappear completely.

“Seeing these significant shrinkages and even complete remission in such a small subset of patients is quite remarkable,” said study first author Dr. Juan Osorio.

He said the effect wasn’t limited to tumors that were injected with the drug; tumors elsewhere in the body either got smaller or were destroyed by immune cells.

“This effect—where you inject locally but see a systemic response—that’s not something seen very often in any clinical treatment,” said Professor Jeffrey Ravetch who oversaw the study.

“It’s another very dramatic and unexpected result from our trial.”

ANOTHER BREAKTHROUGH: Lung Cancer Drug Elicits Unprecedented Results in 2024 Trial

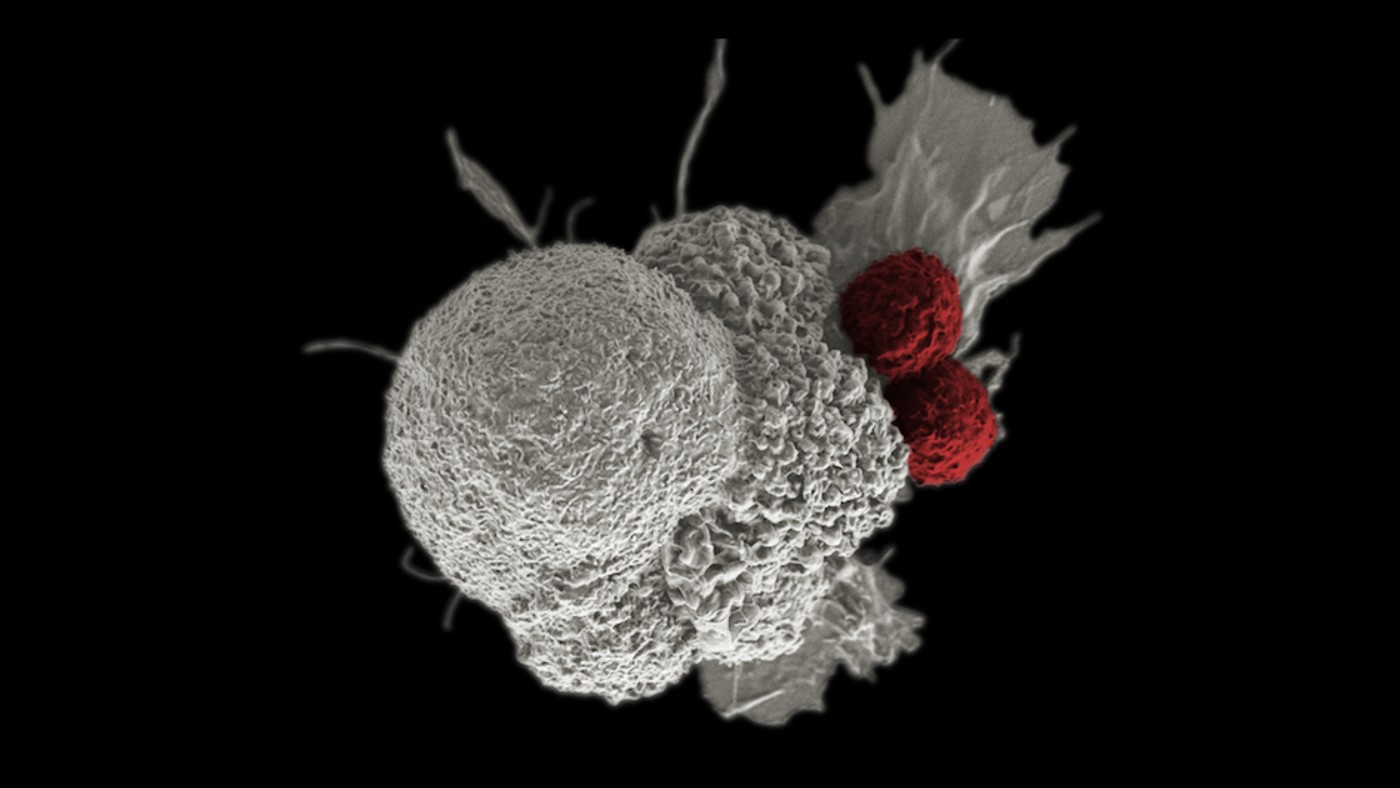

He explained that CD40 is a cell surface receptor and member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor “superfamily”—proteins that are largely expressed by immune cells. When triggered, CD40 prompts the rest of immune system to spring into action, promoting anti-tumor immunity and developing tumor-specific T cell responses.

In 2018, Prof. Ravetch’s lab engineered the 2141-V11, a CD40 antibody that binds tightly to human CD40 receptors and is modified to enhance its cross-linking by also engaging a specific Fc receptor.

It proved to be 10 times more powerful in its capacity to elicit an anti-tumor immune response.

The research team then changed how they administered the drug. When previously given intravenously, too many non-cancerous cells picked it up, leading to the well-known toxic side effects.

They instead injected the drug directly into tumors. When they did that, they saw “only mild toxicity”, said Prof. Ravetch.

ALSO CHECK OUT:

• Cancer Vaccine Triggers Fierce Immune Response to Fight Malignant Brain Tumors in Human Patients

• Oxford Breakthrough Could Allow Cancer to be Detected 7 Years Earlier Than Current Methods

The new trial included 12 patients who had various types of cancer, and of those 12, six experienced systemic tumor reduction, of which two had their cancers (notorious for being aggressive and recurring) disappear entirely.

“The melanoma patient had dozens of metastatic tumors on her leg and foot, and we injected just one tumor up on her thigh. After multiple injections of that one tumor, all the other tumors disappeared,” Ravetch said.

“The same thing happened in the patient with metastatic breast cancer, who also had tumors in her skin, liver, and lung. And even though we only injected the skin tumor, we saw all the tumors disappear.”

Tissue samples from the tumor sites revealed the immune activity that the drug stimulated.

“We were quite surprised to see that the tumors became full of immune cells—including different types of dendritic cells, T cells, and mature B cells—that formed aggregates resembling something like a lymph node,” said Dr. Osorio.

“The drug creates an immune micro-environment within the tumor, and essentially replaces the tumor with these tertiary lymphoid structures, which are associated with improved prognosis and response to immunotherapy.”

BRILLIANT: Glowing Dye Clings to Cancer Cells Giving Doctors ‘Second Pair of Eyes’

The team also found TLS in the tumors they didn’t inject.

“Once the immune system identifies the cancer cells, immune cells migrate to the non-injected tumor sites,” said Dr. Osorio.

The findings, published in the journal Cancer Cell, sparked several other clinical trials that the Ravetch lab is currently working on with researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering and Duke University.

The trials are investigating 2141-V11’s effect on specific cancers, including bladder cancer, prostate cancer, and glioblastoma—all aggressive and hard to treat.

Nearly 200 people are enrolled in the various studies that the researchers hope will explain why some patients respond to 2141-V11 and others do not—and how to potentially change that.

SHARE THE AMAZING NEWS With Patients on Social Media…