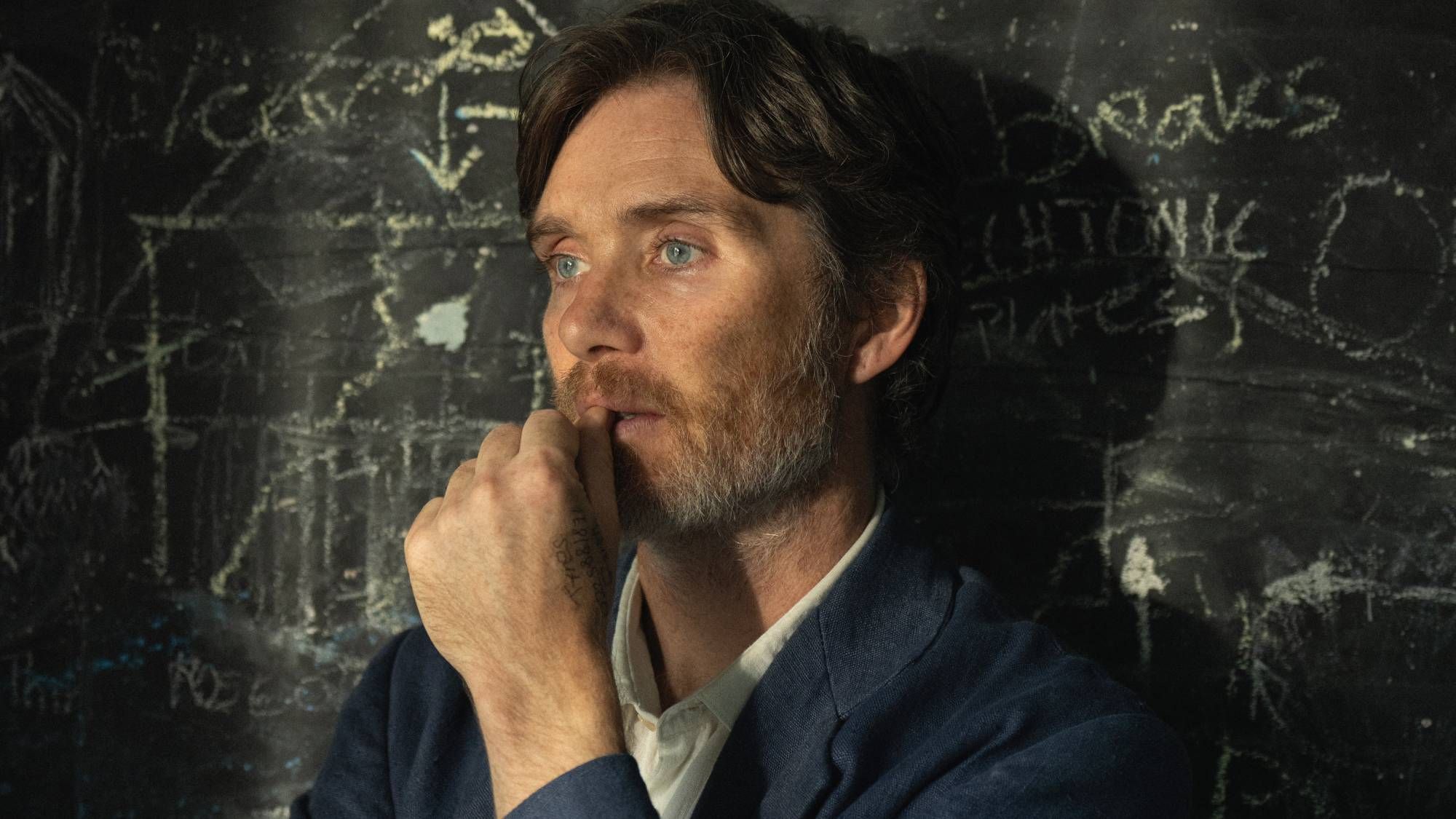

EXCLUSIVE: Oscar winner Cillian Murphy’s next feature, Steve, will world premiere at the Toronto Film Festival before receiving a theatrical release in select cinemas September 19, then dropping on Netflix on October 3. We’ve got a fresh exclusive image from the movie, and also recently caught up with star-producer Murphy along with Steve writer/executive producer Max Porter; director Tim Mielants; and Murphy’s producing partner Alan Moloney with whom he founded Big Things Films, which produces Steve in collaboration with Netflix.

The drama, which also features some darkly funny moments, is set in the mid-1990s and follows a pivotal day in the life of the titular headteacher and his students at a last-chance boys’ reform school amidst a world that has forsaken them. As Murphy’s Steve fights to protect the school’s integrity while also fighting its impending closure, he grapples with his own mental health. In parallel to Steve’s struggles, troubled teen Shy (Jay Lycurgo) is caught between his past and what lies ahead as he tries to reconcile his inner fragility with his impulse for self-destruction and violence.

This is a reimagining of Porter’s 2023 novella Shy, and takes place on a day where a documentary TV crew is interviewing the teens and the teachers. It functions as well as a commentary on the political present, which Porter discusses below.

Steve also stars Tracey Ullman (in a rare, and stunning, dramatic turn), Top Boy’s Simbi Ajikawo (aka Little Simz) and BAFTA winner and Oscar nominee Emily Watson.

Murphy likes to surround himself with familiar collaborators, and has done so again with Steve. He previously starred in the stage adaptation of Porter’s Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, winning raves for the performance. They later worked together on the short All of this Unreal Time. Murphy also has a long history with Mielants, going back to Season 3 of Peaky Blinders, and more recently Big Things Films’ first feature, 2024’s Small Things Like These. Watson was in Small Things, too; and it’s on Steve that Murphy first worked with Lycurgo, who is in the upcoming Peaky Blinders feature.

In a Q&A below, Murphy, Porter, Mielants and Moloney discuss the film’s genesis and themes, casting, collaboration and the balance of telling tough stories that remain entertaining.

(This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

DEADLINE: One thing I’m positively dying to know about is the casting of Tracey Ullman. During the screening I saw, I found myself saying, “Is that Tracey Ullman? No, can’t be. Wait, yes it is!” She is so good in such an unexpected role … How did that come to pass?

TIM MIELANTS: I think Tracey was Cillian’s idea.

ALAN MOLONEY: I think it was Yvonne (McGuinness, Murphy’s wife).

CILLIAN MURPHY: Yeah, it was Yvonne. Most of my ideas come from my wife, my good ideas.

I knew Tracy before. She was going out with a friend of mine, and we had hung out, and I’m such a fan of her. She’s such an icon. And then Yvonne knew her as well. But then Yvonne heard her on some podcast, and she was saying, “I’ve always wanted to be in like a Ken Loach movie.” And we were like, “Well, this isn’t quite Ken Loach, but…” And then I called her up and I said, “There’s this script I have, and that Max has written, and would you take a look?” And it’s like everyone who read the script, they responded like calling in floods of tears, going, “Yes, yes, yes.” And she immediately came back and said yes. It was amazing.

DEADLINE: OK, thanks for clearing that up… Max, you and Cillian have worked together before, but how did this project come about.

MAX PORTER: Just purely out of conversations, and Cillian had got back off the very intense period of work he’d been doing, and said, “Would you consider writing me something again?” I had just come off the Shy book tour, and I said to him that one of the things that keeps on happening is that people keep on standing up at the end of my events. And I expected some people to say, you know, “I was Shy, and I liked this and understood this book,” and I expected people to say, “I’m a parent of a Shy and I liked and understood this book.” But what was happening more and more was that people were standing up saying, “I’m a teacher or carer or run a facility for kids comparable to this.” Their feedback was the thing that was sort of most generative for me and most interesting. So I had this idea that we could, you know, rewrite the whole book, twist it on its axis from Steve’s point of view.

So he told me to have a go at it. And I did, and then when I was done with it, took it straight to Alan. Alan will tell you about the very expensive lunch I bought him when we first met.

MOLONEY: One of the finest ham rolls, Nancy.

PORTER: I didn’t even pay to eat in, we sat on the steps of the local church.

MOLONEY: Yeah, as it happens, we live close to each other. So it was a nice day out in the leafy suburbs of Bath. We’d read a copy of the book…. and very quickly we hatched out a plan to get it from that to script. It took probably about three or four months, but Cillian and Max had sort of identified the Steve part of the story.

DEADLINE: Cillian, how involved were you in developing your character with Max?

MURPHY: Like Max said, we talk all the time, and we get into it — we don’t do small talk, we go straight into it. I gotta say, it was one of the most kind of exposing and terrifying characters I’ve ever played, because it was written bespoke for me by Max, but also had, I think, quite a lot of him in there… There’s elements that I feel like, you know, there was no accent.

DEADLINE: I was gonna say, you actually sound like you, which is rare…

MURPHY: Yeah, and Max knows me so well at this stage, he would kind of write for the way I go on and talk. So, it was quite terrifying, because there’s no real prep needed. Both my parents are teachers, so I grew up in a household where I saw the after effects of standing in front of 35 teenagers all day long while my mother was trying to raise four of her own, and they were both out at work. My grandfather is a headmaster. All my aunts and uncles are teachers. So I know that inside-out of that world. This is a more extreme world, clearly, because you’re dealing with these very volatile and unpredictable and damaged kids. But having said that, I kind of knew it, but I couldn’t have done it without knowing the people like the way I know these guys so well and trust them so much, because there was really no acting involved. It was kind of like reacting or existing or being and being available and being porous and being just completely without filter or anything like that. And it was f*cking scary in a great way, and it’s a very exhilarating way, but like, just you’re in this jangled state of anxiety for two months.

Alan Moloney, Max Porter and Tim Mielants

Courtesy

MOLONEY: Interestingly, we shot it in sequence, so you kind of knew what was coming the next day. But emotionally, I think that had an impact on sort of everybody, because we all knew where Steve’s character was heading. And we were watching Cillian inhabit this character. Every day he was a slightly other shade of gray; it was kind of progressing in a direction, and I find the whole thing quite emotional because of all of that. It was very, you kind of feel it in the air.

DEADLINE: I can only imagine. I mean, it certainly translates to the screen. I was a mess at the end.

MOLONEY: We were all a mess in the car park.

PORTER: There was real, real feeling. Tim and I, in fact, all of us, were having conversations with one another about whether we were okay and the extent to which this was hurting, and obviously, with a compassionate umbrella over us that we were looking after each other on set and everything, but understanding that there was nowhere to hide. You know, particularly for Cill and for Jay, there’s no costume, there’s no superhero cloak for a young actor like that. But I think what Tim has kept in the film is an extraordinary aura of truth-telling around these performances. I can’t think of a note in this film that has any inauthenticity or artificiality about it, because everybody plugged right into it from where they were coming from.

DEADLINE: Speaking of Tim, how did it happen that he turned right back around for this one just after Small Things?

MURPHY: The first time myself and Max spoke about it, I immediately said that Tim should direct it, like, straight away, from before there was even a script. I said it has to be Tim.

DEADLINE: And, Tim, were you on board right away?

MIELANTS: I’m always anxious when I read something. I think I’m gonna screw it up. So I was more like, okay, how am I gonna do it? I loved it, but it was a script you don’t often come across. It was ambitious, that’s the beauty of it. And then we started talking about it and working on it, and then other elements came in.

DEADLINE: Can you talk about those?

MIELANTS: Throughout the making of the movie, in a very, very close collaboration with Max, I remember (suggesting), “What if you make interviews with all the different characters there? Because if I would be a documentary filmmaker, I would go to the kids and find the beauty in the pain.”

Max started writing all these beautiful interviews, and they became part of the movie as well. And it starts evolving all the time. The script was already there, and that’s also the movie. But we kept working and thinking and talking about images and possibilities. It was really a collaboration I’ve never experienced before. Small Things was kind of in my head before I started, and this was, like, along the way, it became bigger and beautiful, but we did it all together. And that was an amazing experience.

DEADLINE: There’s a sense with those interviews that the boys might just be riffing, but that’s not actually the case…

MURPHY: People have been asking me this, they’re like, “Oh, it was so great seeing those kids improvise those interviews.” And, I say, “No, no, no, no, they did not improvise those interviews. That is all scripted, every last part of it.” They can’t believe it. But that’s Max’s writing.

DEADLINE: And some of the kids had never acted before, so how do you get that authenticity?

MIELANTS: I think the reason why it’s so natural is Max wrote it, and he knows his characters so well, and then we went into a rehearsal period where Max was there all the time. Me and Max were talking one-on-one with all these kids, and they talked about their problems. And I think Max started kind of mixing the real kid and the character kid together somewhere. Sometimes we were inspired by some of the kids who never acted before, and they became the character, and the character became them.

PORTER: We managed to keep it alive. And that crucial week, spending time with the boys, particularly, but also seeing how they were responding to each other… I knew the script was unconventional. I had hoped that we would maintain some of that texture, but in fact, the way that Tim has edited those interviews gives you a texture that’s a very novelistic texture. It has the fabric of the juxtapositions that are so precious to me on the page because they allow your viewer to feel things very, very deeply and to kind of collaborate with the texture of the piece in order to feel. So, when the boys started saying to me, “Could I be Cornish?” or, “Could I actually be a little bit reserved?” or “Could I find the bullying actually hurts me?”… For a writer to have the opportunity to tweak the script as we’re filming it was absolutely glorious.

DEADLINE: Yes, that’s an amazing opportunity – and rare for a writer to be on set the whole time.

PORTER: (Laughs) I just like the free food, really…

DEADLINE: In the film, sometimes there’s this frenetic pace, and then there’s this quite slow pace, and at times the camera work flips. Tim, can you talk about that?

MIELANTS: You’re totally right. It’s kind of what I do if we get a period case, I go to the movies back in that time. I was 16 in 1996 so, what movies were around, and what kind of movies did I love? And we felt that the dogma style, the Lars von Trier style at the beginning stood the storytelling because you’re very intrigued by the character of Steve, but you can’t really figure it out. That’s what von Trier did with his DPs: He didn’t tell them the blocking, and then he threw them in the middle.

But then at the moment when we start to know the character a little bit better, I think we’re more observing in a way. We’re going from dogma style to Requiem For a Dream. We start to observe him a little bit, we start looking at him with empathy, and that’s kind of these two extreme genres. That’s the kind of art we’re doing camera wise. But it works because the emotions are so extreme that the different elements are so extreme. It’s a kind of a love letter to the 90s style-wise.

And we’re kind of going through every genre… and the surreal elements.I just saw them in front of me… I don’t know why I suddenly wanted to shoot stuff upside down. I just saw things upside down and I started shooting.

DEADLINE: Max, is there a reason you set it in that time period?

PORTER: I wanted to write somewhat about the political present in the UK during the decimation of the conservative government’s work with social care and our various infrastructures and systems that have been so despoiled by greed and corruption over the last 15 years. But I didn’t want to write an obvious piece. I thought the distance would help, particularly also for a kind of cause and effect, you know, what happens if you dismantle this system? What happens to young people if you close these schools specifically?

But also for me, the texture of the bullying and the communication of the children, it was very important and interesting to do it before mobile phones, which have been such a paradigm shift. And then when it came to whether we should keep it in that period for the film, Tim had this connection to movies at that time. I felt very strongly that the music and the fashion of that time would be really interesting. I think in terms of creating an esthetic, particularly with the documentary film crew, it was just too irresistible to create a period piece. It’s like a historical drama, but it’s recent enough that these are all things that we’ve been in or fed from.

DEADLINE: I don’t mean this to sound reductive in any way, but I probably saw this film shortly after I had watched Adolescence, and just young boys and bullying doesn’t mean that it all goes in one pot. I know, Cillian, you don’t like to like tell people what to think about a movie, but I wonder if you could expand on how Steve relates to today, through that period setting.

MURPHY: It never goes away. That stuff just exists, right? But like you mentioned Adolescence, I think that that is sort of the landmark piece of television, I think, it’s one of the greatest things I’ve ever seen. And definitely there’s a sort of a thematic crossover to a degree, but I think it was very smart of Max to set it in the 90s, to show this sh*t still exists. People are still, kids are still wounded and vulnerable and alienated without social media. You know, they still need human interaction. They still need face-to-face connection to get to them. You know what I mean, that’s just perennial, that just exists.

And yeah, you’re right, I always find it difficult to engage in a kind of a prescriptive, dogmatic way before the audience see it. Because I think the audience will tell us what they think. It was like when we made Small Things Like These, and we started showing it to people in Ireland, particularly, people responded in a way that was overwhelming. And then we could feed back to the audience. And I feel like when the audience sees this, like Max said, when people read his book, that they were like, “I see myself, I see my sister, I see my dad…,” you know, they would see things in it, and then the conversation will begin. So I’m kind of very reluctant to go, “This is what you should feel. This is what the film means. And give us 10 out of 10.” I really don’t feel in the position to do that ever. And I don’t think the film is finished until the audience sees it.

MOLONEY: I think there’s another aspect which is probably worth saying, which is, Adolescence — and I would echo Cillian, is an extraordinary piece of television — I think it’s significant that that and Steve are on Netflix. I think, to a degree, there’s a public service aspect to the broadcasting, and there is a broadsheet kind of environment with which to offer for discourse and debate that did, obviously come out of Adolescence, and we would hope comes out of this. And, crucially, when you look at the amount of people who watched Adolescense, there is an audience out there that wants to be challenged, and has an appetite for what would be, I suppose, described as difficult stories. And the truth is, they’re not actually difficult stories. It’s tough material, but it’s stuff that we need to consider, and we need as a society, to discuss and debate, and it’s really important that Netflix is doing it, because, frankly, nobody else is doing it right.

PORTER: I was sort of anticipating a comparison and a sort of shared conversation around them, and I left it quite late to watch Adolescence, because I don’t watch things if Keir Starmer tells me I have to. But I thought it was honestly, utterly astonishing. I thought really, beyond their subject matter of masculinity or whatever, beyond what they what they appear to have in common, politically, what they both struck me as having in common, and as Alan says, this is huge props to Netflix for making this work, is that they both do a notionally difficult thing. They smuggle deep meaning and layer the layers of discourse into a thing that was also primarily and overwhelmingly colossally ambitious as film, like those single shots in Adolescence and Tim’s approach to the montage and the work and the work that you then get out of your actors if you put them under that kind of pressure, like what happened particularly to Jay and Cill and Simz and Emily, Tracey as well, under the pressure of Tim’s gaze, which is why he’s such an extraordinary filmmaker, because he looks at people like some kind of Dutch master painter; he’s working round people in a room, asking them to go a little bit harder or a little bit deeper, or turn a scene on its head and see if it yields if you try it from a completely different angle. That works so well with political subject matter, because it doesn’t just become prescriptive or illustrative. As everyone keeps saying, it’s not our message. It becomes the viewers’ collaboration, which unlocks the message — if there is one inherent — and I just love that about both these pieces of work.

MURPHY: I’d like to add as well, just on that, that I think neither Adolescence or hopefully our film will succeed unless it’s entertaining. You can have a boring polemic and no one’s gonna get engaged with it. No one’s gonna have a discussion about it. But Adolescence is monstrously entertaining, as well as being soul crushingly moving, and hopefully our film is as entertaining as it is, kind of engaging politically or whatever. I think your first duty is to entertain, and then after that, like Max said, you can smuggle stuff in, and if you can do that elegantly, I think then you’ve won.

DEADLINE: Alan and Cillian, this being the second Big Things, production, what, if any sort of lessons have you taken from this one?

MOLONEY: Oh, God, that’s a big question, Nancy. I think it is probably, you know, look, we’re really pleased with the film. Really, really pleased. I think it is the film we set out to make in the same way that Small Things was. I think it has probably only further confirmed, for me at any rate, that if we trust our instinct, that we have the capacity to make the films that we set out to make.

It is, again, always about working with great people. It’s really just confirmed the reason why we wanted to make films together was exactly for this reason.

MURPHY: It’s exactly that. I mean, it’s no coincidence that they’re both directed by Tim. We got very, very lucky the fact that we have this incredible director that’s made two unbelievably different films so, so brilliantly. And, to have that level of trust, like I said to you at the beginning — and I’ve always said this about working — for me, the trust thing is the kind of most important thing. The scene in the basement when Steve goes down and screams at himself, that couldn’t have happened if I wasn’t working with these people… It’s because of the relationship I have with Tim. So for me, I think there’s something in the relationships that have made manifest in these films. And I’m really, really proud of that.

MOLONEY: Both of them are, on the face of it, challenging films to make. And I think the confidence that Tim brings to that just takes so much kind of fear and worry away.

PORTER: So let’s just carry on blowing smoke up Tim’s ass for a sec because this was a very unconventional script, and it posed a series of logistical problems. The level of Tim’s work, figuring that out way in advance and in watching his drawings, watching his storyboarding, watching the way he communicates with his team. At various points in the shooting of it, I would say to Cillian — I’m careful not to pay him compliments — but the quality of the work was something else. Never in your wildest dreams as a writer do you see this landing as hard and as powerfully as he’s been capable of here. And he would often say, “Tim can just get this out of me and this is what Tim does when you get us in a room together.” So I think that’s right. It’s a testing of and an honoring of the relationships that already existed and pushing it further.

MOLONEY: It’s worth saying about Cillian’s performance, because I love embarrassing him, but it is an extraordinary performance. As you know, you’ve seen the film, he just nails it. I mean, it just gets better and better.

MIELANTS: I really would like to express that we did it really all together. I think Cillian was so helpful in the edits. Of course, his performance is mind-blowing. Nobody knows this, but actually he’s a very good editor. And yeah, I think he should be an editor on the side of some I don’t know… We just have a good team that rolls.

DEADLINE: Small Things opened Berlin, and then Steve will world premiere in Toronto, and you’re also getting a theatrical release. All of this speaks to award season, so can you talk to me a little bit about why Toronto and how that came about and why that festival felt like the right place?

MOLONEY: We wanted the film to have that theatrical release, and Netflix were good enough to support that, and the nature of the film is such that we believe it needs to be best seen in a festival environment and reviewed in that way… There’s DNA of independent film all over this piece, and it sort of sits in a particular space. So we wanted to be judged on those merits. Toronto is a festival that has always been very kind to us, has a great audience. Obviously, we are multinational, but it’s an English (language) film, so to take it to North America felt like strategically the right thing to do.

DEADLINE: And then you’re having a European premiere in Cork.

MOLONEY: It’s a festival that Cillian is associated with in Cork, and we wanted to do something in Ireland. Cork is obviously Cillian’s hometown, and so the timing of it all just worked the way it did. It feels like the right thing to do. We are very excited about that, very excited to go to Cork. And people from Dublin, as I am from, don’t go to Cork very often.

DEADLINE: Speaking of Ireland in general, Cillian, are you guys making headway on that cinema that you and Yvonne bought in Dingle, County Kerry?

MURPHY: Yeah, we are. We’re working away. We’re just doing public consultation now with the community, and we’re fully, fully engaged in it. And it’ll take a while, but we’re determined to get it going.

DEADLINE: Otherwise, we know you wrapped the Peaky Blinders movie, but what’s next on the docket?

MURPHY: I’m kind of taking the year off. I’m doing this work, but I’m not actually acting on anything, which is nice for a while. I’m just waiting for Tim to cast me in his next film.

DEADLINE: This is totally aside, but you are definitely in 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, right?

MURPHY: I think Danny (Boyle) has already confirmed that. So I can confirm.

DEADLINE: And you would be sort of the focal point of the third movie. If the third movie gets green lighted.

MURPHY: Exactly, so in order for that to happen, every single person has to go and see Bone Temple.

Source link