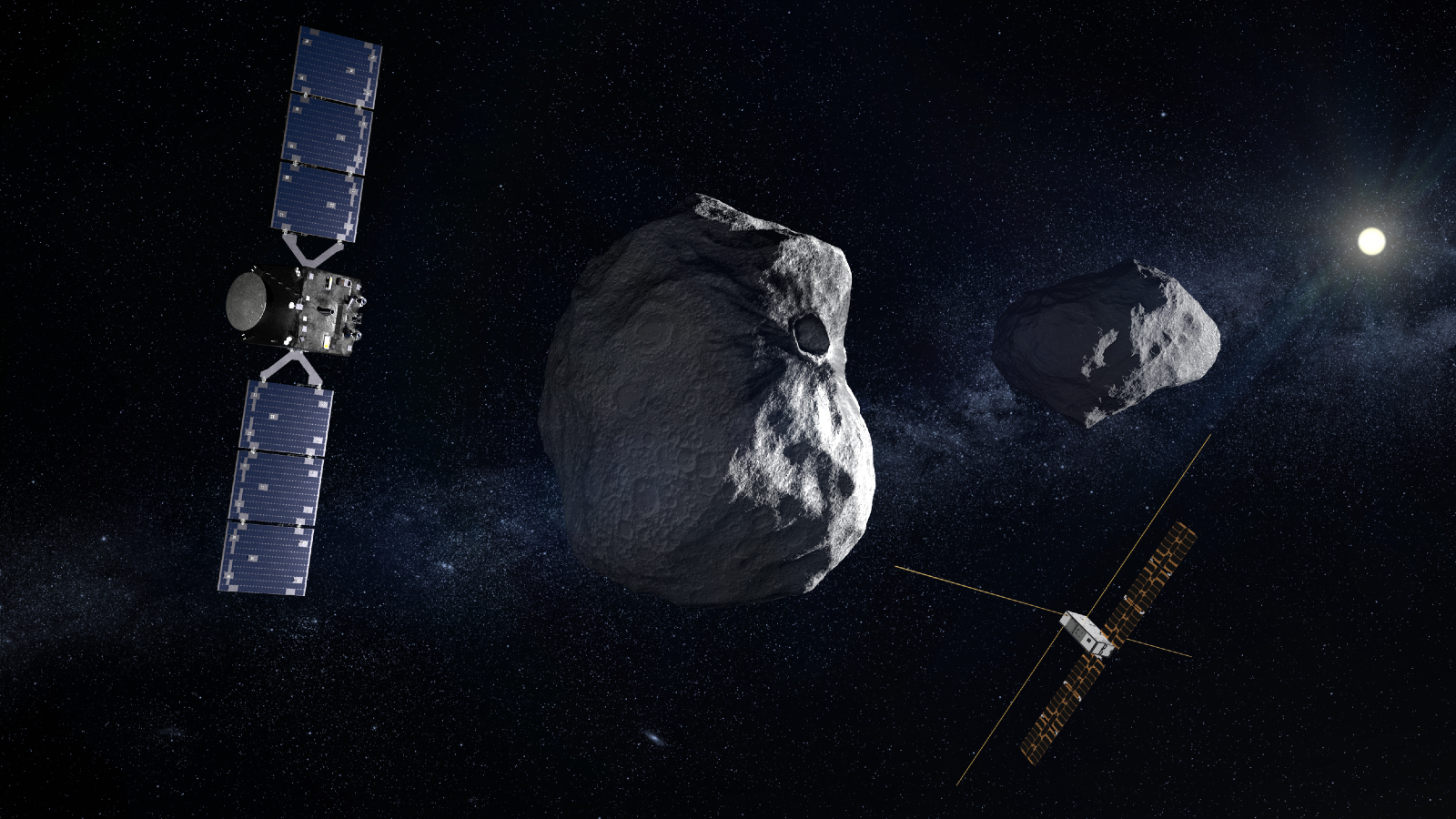

The Hera mission to follow-up on the aftermath of NASA’s DART asteroid crash has caught sight of two other asteroids in an important test of its camera ahead of its rendezvous its main target: the double space rock system of Didymos and Dimorphos.

In September of 2022, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART for short, slammed into the small asteroid Dimorphos, which orbits the larger Didymos, to demonstrate how potentially hazardous asteroids that could one day be on a collision course with Earth could be bumped off their trajectories so they miss our planet.

Two years later, on Oct. 7, 2024, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched the Hera mission that is currently on its way to Didymos and Dimorphos to observe in detail the effect that the DART impact had on both asteroids.

In March of 2025, Hera had a close encounter with Mars, using the Red Planet’s gravitational tides to slingshot through the asteroid belt. And speeding through this zone of space rocks has been an ideal opportunity to test out some of Hera’s instruments.

“The Hera spacecraft is performing very well,” said Giacomo Moresco, who is Flight Dynamics Engineer at ESA’s European Space Operations Center, in a statement. “So, we can use the cruise phase to test procedures and carry out other activities that will help us prepare for arrival, such as attempting to observe nearby asteroids.”

Unlike depictions in popular media, the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter is pretty sparse. It is mostly empty space and, usually, if you dropped a pin to a random part of the belt, the closest asteroids would be millions of miles away. This posed a challenge for Hera, which is indeed not currently close to any denizens of the asteroid belt.

It was the duty of ESA’s Flight Dynamics team to identify which asteroids Hera might be able to image, program commands to prompt Hera to slew towards and target the chosen asteroids, then make sure Hera can follow a pre-determined sequence of observations. It took Moresco’s team a couple of weeks to sort it all out.

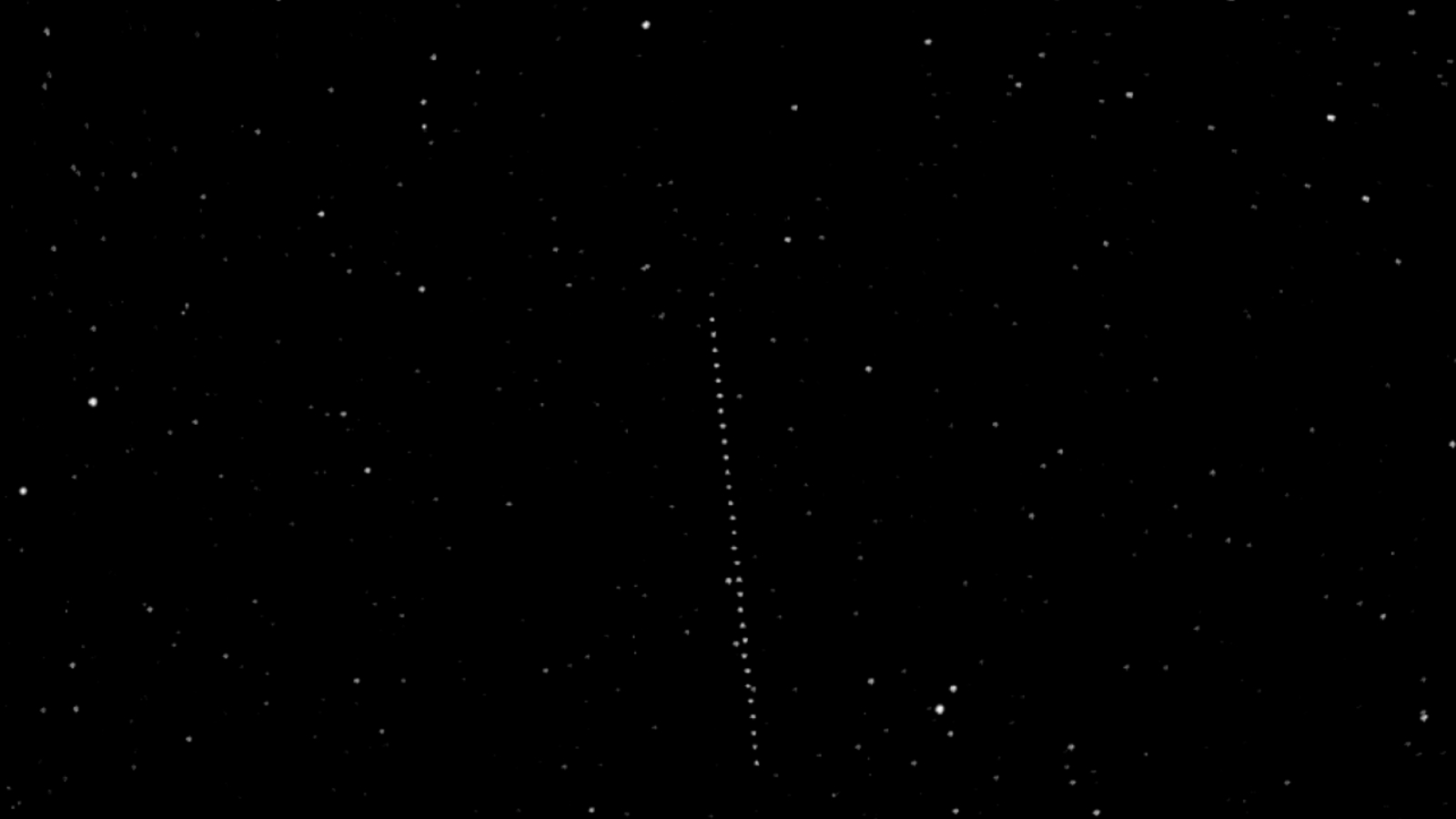

The asteroids they chose were (1126) Otero and (18805) Kellyday, neither of which are particularly well known. Both are also very distant and very faint. However, imaging them would mimic the conditions in which Hera’s Asteroid Framing Camera will first spot Didymos and Dimorphos.

“Didymos will also be a tiny, faint point of light among the stars when it first appears,” said Moresco. “The spacecraft will need to identify Didymos as soon as possible and keep the asteroid in the center of the camera’s field of view as it approaches.”

First up was Otero, on May 11. Discovered in 1929 by the German astronomer Karl Reinmuth, it is named after the Spanish courtesan and dancer Carolina Otero. The asteroid is a rare example of an A-type asteroid, which are typically found in the inner asteroid belt and have a reddish spectrum with a strong chemical fingerprint of the mineral olivine. A-type asteroids are thought to have come from the mantle of a larger protoplanet that smashed apart long ago.

Hera’s Asteroid Framing Camera tracked Otero for three hours, snapping an image every six minutes. Some 187 million miles (3 million kilometers) from Hera, the asteroid appeared merely as a faint point of light — but over the course of those three hours, it began appearing as a trail moving against the background stars.

Then, on July 19, Hera imaged Kellyday, which is named after U.S. high school student Kelly Jean Day, who won third place in the 2003 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. One of the prizes was to have an asteroid named after her (one hopes ESA has sent her the image of her asteroid!).

The challenge in imaging Kellyday was that to Hera it appeared 40 times fainter than Otero.

“So, these observations really pushed the limits of Hera’s faint object detection and of our image-processing capabilities,” said Moresco. “But nonetheless, we spotted it!”

All in all, imaging the two asteroids was a very successful test of Hera’s Asteroid Framing Camera and the spacecraft’s ability to target faint asteroids in preparation for the day it catches sight of Didymos and Dimorphos.

There is also an added twist to being able to take images of Otero and Kellyday. Now that the Flight Dynamics team have sussed out how to reorient the Hera spacecraft and use it to image faint targets, the spacecraft could potentially be used to keep an eye on any newly discovered but potentially hazardous asteroids, helping astronomers to calculate the asteroids’ orbit and determine whether any will collide with Earth. Alternatively, Hera could also be requisitioned to image interstellar objects like 3I/ATLAS that arrive suddenly on the scene and prompt a rapid scramble to image them.

“By demonstrating that we can safely and efficiently command Hera to observe a new target on short notice, we are building confidence for the mission’s science phase, while also demonstrating a potential framework for rapid-response observations of interesting objects in deep space,” said Moresco.

Hera is set to arrive at Didymos and Dimorphos in late 2026 to begin a six-month mission characterizing the two asteroids and observing DART’s impact site.

Source link