The wrists of birds are incredibly complex and functionally crucial in both flight and the folding of wings at rest, says Will Newton.

To stabilise their wings during flight, birds rely on a tiny bone known as the pisiform. This bone was long thought to have been lost in the early ancestors of birds, only returning as they started to take to the skies and evolve into the birds we know today.

However, CT scans of two small, flightless theropod dinosaurs – an unnamed troodontid and an oviraptor known as Citipati from the Late Cretaceous (75 to 71 million years ago) – have revealed the presence of pisiforms in their wrists. These dinosaurs were discovered in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert and recently prepared for close examination.

“Wrist bones are small and even when they are preserved, they are not in the positions they would occupy in life, having shifted during decay and preservation,” said Alex Ruebenstahl, a co-author of the new study, in an associated press release. “Seeing this little bone in the right position cracked it wide open and helped us interpret the wrists of fossils we had on hand and other fossils described in the past.”

Prior to this study, pisiforms were only identified in the earliest theropod dinosaurs – a group of meat-eating dinosaurs that includes famous species such as T.rex and Velociraptor.

The discovery of pisiforms in the wrists of the aforementioned theropod dinosaurs suggests the bone ‘re-appeared’ a lot earlier than first thought. It also established its presence in Oviraptorosauria and Troodontidae, in addition to later birds.

Based on their discovery, Ruebenstahl, lead author James Napoli, and co-authors Matteo Fabbri, Jingmai O’Connor, Bhart-Anjan Bhullar, and Mark Norell examined fossils from a wide range of theropod species, including Microraptor,Ambopteryx, and Caudipteryx. Knowing what to look for, the team found pisiforms in all three of these dinosaurs and more.

A key change in the transformation of forelimbs to wings was the replacement of another wrist bone – the ulnare – with the pisiform. “The pisiform, in living birds, is an unusual wrist bone in that it initially forms within a muscle tendon, as do bones like your kneecap – but it comes to occupy the position of a ‘normal’ wrist bone called the ulnare,” said co-author Bhullar.

The results of this new study indicate the pisiform replaced the ulnare before the origin of the clade Pennaraptora – a group of raptor-like dinosaurs who can trace their roots all the way back to the Late Jurassic, roughly 160 million years ago.

This pushes back one of the key mechanisms in the origin of bird flight by tens of millions of years. It also quashes the previous assumption that flight-stabilising pisiform bones were a novelty restricted to just birds; they were also present in near-bird dinosaurs who were just starting to experiment with the power of flight.

This study is published in the journal Nature and is a collaboration by palaeontologists from Stony Brook University, Yale University, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Mongolian Academy of Sciences.

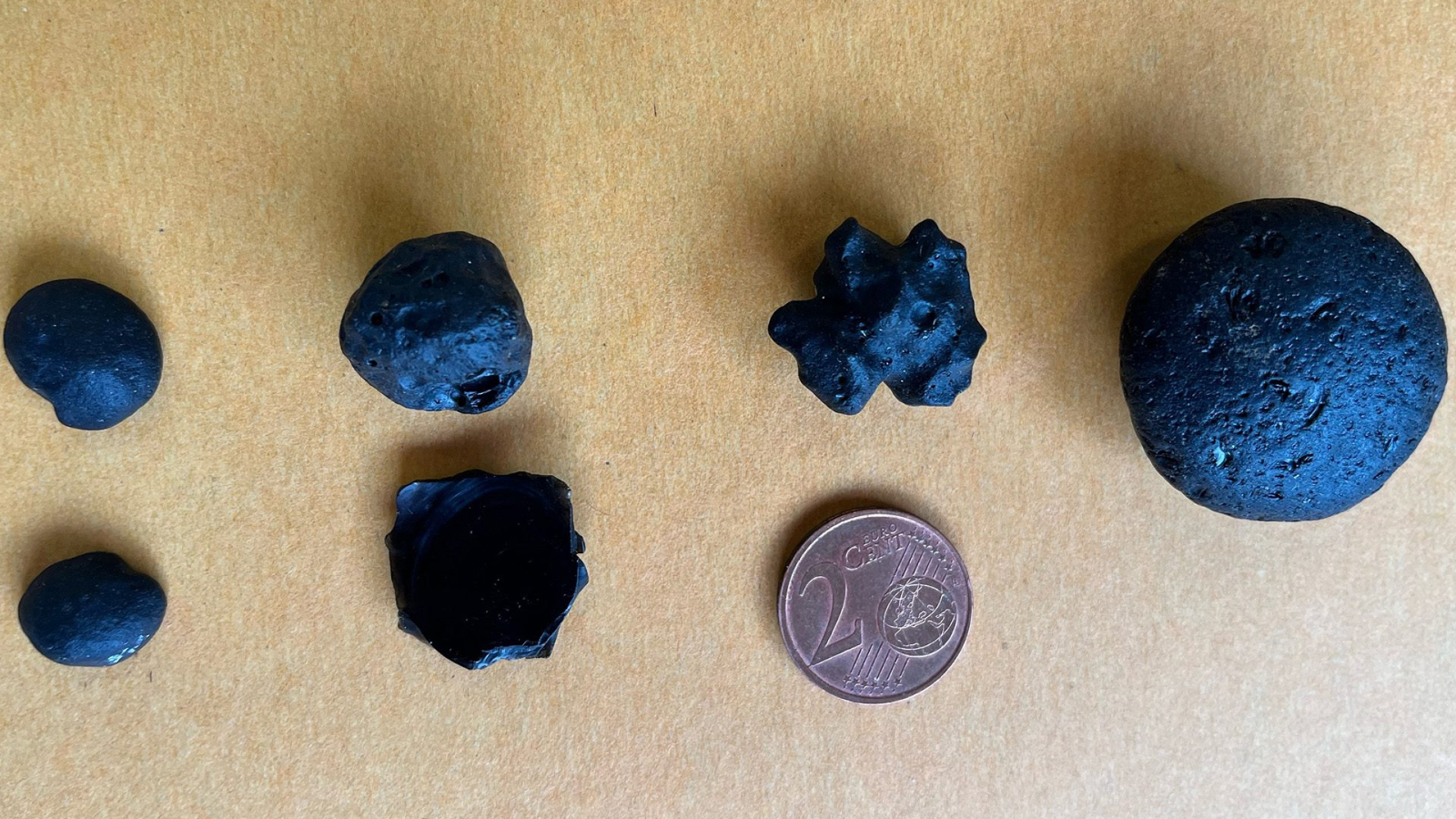

Main image: A life reconstruction of the specimen of Citipati, a dinosaur closely related to birds, analyzed with an x-ray cutaway of the specimen’s wrist. The small and rounded pisiform is highlighted in blue.

Credit: A life reconstruction of the specimen of Citipati, a dinosaur closely related to birds, analyzed with an x-ray cutaway of the specimen’s wrist. The small and rounded pisiform is highlighted in blue. © Henry S. Sharpe/University of Alberta

Source link