A new discovery in the Grand Canyon is giving scientists a closer look at some of Earth’s earliest animals. This stunning find includes fossils of soft-bodied creatures from more than 500 million years ago.

These aren’t just any fossils – they offer a rare glimpse into how early animals lived, fed, and evolved during a time of rapid biological change.

The fossils were found in rocks that date back to the Cambrian explosion. This period, between 507 and 502 million years ago, marks when many of the major animal groups first appeared.

Intense competition and evolutionary innovation marked this window in time. For the first time in this famous national park, scientists have found exceptionally preserved remains of soft-bodied animals, such as mollusks, crustaceans, and even fragments of their last meals.

A microscopic fossil treasure

Researchers from the University of Cambridge led the study. They collected rock samples during a 2023 expedition along the Colorado River in Arizona.

“We collected a total of 29 samples of diverse shale lithologies, ranging from massive to fissile, gray to purple, and with various degrees of weathering and dolomitization,” the team noted.

The researchers brought the samples back to their lab, where they dissolved the rocks using hydrofluoric acid. After running the sediment through sieves, they uncovered thousands of tiny fossils.

“These rare fossils give us a fuller picture of what life was like during the Cambrian period,” said first author Giovanni Mussini, a Ph.D. student in Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences.

“By combining these fossils with traces of their burrowing, walking, and feeding – which are found all over the Grand Canyon – we’re able to piece together an entire ancient ecosystem.”

Early animals had wild ways to eat

The level of preservation is remarkable. Although the fossils weren’t fully intact, the researchers were able to identify structures like spiky teeth, scraping tools, and feeding limbs. These features show how the creatures once lived.

Scientists usually see this kind of fossil preservation only in places like the Burgess Shale in Canada or China’s Maotianshan Shales.

Some of the most surprising finds were animals with complex feeding tools. “These were cutting-edge ‘technologies’ for their time, integrating multiple anatomical parts into high-powered feeding systems,” said Mussini.

Among the fossils were tiny crustaceans resembling modern brine shrimp. They had grooves around their mouths lined with hair-like structures and molar-like teeth that allowed them to grind food efficiently.

Tiny grooves and fossilized food particles near their mouths gave clues about what they were eating.

Fossils reveal feeding variety

The fossils also showed slug-like mollusks with chains of teeth similar to modern garden snails. This suggests they scraped algae or bacteria from rocks.

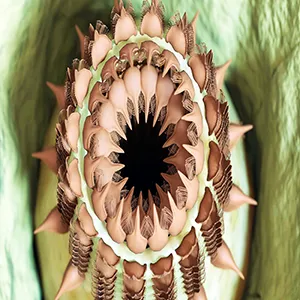

A priapulid worm – commonly known as a cactus worm – stood out as the most unusual creature, with complex rows of branching teeth.

The researchers named it Kraytdraco spectatus, inspired by the krayt dragon from the Star Wars universe.

“We can see from these fossils that Cambrian animals had a wide variety of feeding styles used to process their food, some which have modern counterparts,” said Mussini.

Perfect conditions to evolve

Half a billion years ago, the Grand Canyon area was much closer to the equator. It was a place where shallow, oxygen-rich waters met just the right amount of sunlight and nutrients.

This balance provided ideal conditions for early animals to evolve and experiment with new traits.

“Animals needed to keep ahead of the competition through complex, costly innovations, but the environment allowed them to do that,” said Mussini. “In a more resource-starved environment, animals can’t afford to make that sort of physiological investment.”

“It’s got certain parallels with economics: invest and take risks in times of abundance; save and be conservative in times of scarcity.”

These fossils show that early animals weren’t just surviving – they were adapting, experimenting, and thriving.

Thanks to their preservation in the fine-grained rocks of the Grand Canyon, we now have a clearer image of an ancient ecosystem that helped shape the diversity of life we see today.

The full study was published in the journal Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–