The Iron Age was one of the most significant epochs in human history, and researchers may have uncovered the secrets of how we left the Bronze Age behind – via a 3,000-year-old smelting workshop called Kvemo Bolnisi, in southern Georgia.

This is a site that’s been pored over before, but anthropological archaeologists Nathaniel Erb-Satullo and Bobbi Klymchuk, from Cranfield University in the UK, wanted to take a fresh look at the evidence.

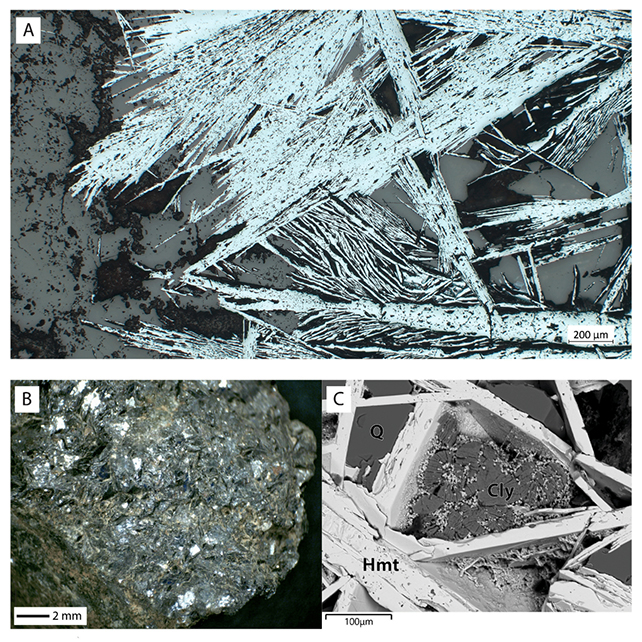

The place was previously thought to have produced iron, due to the extensive amount of hematite (an iron oxide mineral) and slag waste (a byproduct of smelting) found there.

Using chemical analysis techniques and microscopic imagery, the researchers came to a different conclusion: iron oxide was actually being used as a flux, a substance added to smelting furnaces to improve, in this case, copper production.

Related: Iron Age DNA Reveals Women Dominated Pre-Roman Britain

That then suggests that iron was discovered through experimentation in copper smelters, rather than being developed separately. This is something that’s been hypothesized before, but without much direct evidence to back it up.

“It’s evidence of intentional use of iron in the copper smelting process,” says Erb-Satullo. “That shows that these metalworkers understood iron oxide – the geological compounds that would eventually be used as ore for iron smelting – as a separate material and experimented with its properties within the furnace.”

“Its use here suggests that this kind of experimentation by copper-workers was crucial to [the] development of iron metallurgy.”

Once it was underway, the Iron Age – spanning 700 years – marked a significant time of change and disruption for humanity. Farming became more efficient, battles got more brutal, and new tools were developed with this hard, durable metal.

Of course, this is only one location, and the production of iron is likely to have developed differently in different places. However, the researchers do draw comparisons with other similar sites – including one in Israel.

It may also be significant that iron-bearing minerals are often found in the same locations as copper deposits, making it more likely that copper smelting processes regularly involved elements of iron as well.

“Iron is the world’s quintessential industrial metal, but the lack of written records, iron’s tendency to rust, and a lack of research on iron production sites has made the search for its origins challenging,” says Erb-Satullo.

“That’s what makes this site at Kvemo Bolnisi so exciting.”

It’s a fascinating period of history, which is constantly being reassessed. A whole host of other factors, including supply routes, trade deals, and political turmoil also need to be taken into account when considering the transition between the Ages.

As analysis techniques and tools continue to improve, it gives experts a reason to go back and look again at archaeological sites – including the Kvemo Bolnisi one, which has revealed new secrets decades after it was first discovered.

“There’s a beautiful symmetry in this kind of research, in that we can use the techniques of modern geology and materials science to get into the minds of ancient materials scientists,” says Erb-Satullo.

“And we can do all this through the analysis of slag – a mundane waste material that looks like lumps of funny-looking rock.”

The research has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Source link