“In terms of putting things in order, in terms of being able to compare between different regions in particular, and understand that pace of change, it has been really important,” explains Rachel Wood, who works in one of the world’s most distinguished radiocarbon dating labs, the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit.

She and her colleagues date materials including human bones, charcoal, shells, seeds, hair, cotton, parchment and ceramics, but also stranger substances. “We do the odd really unusual thing, like fossilised bat urine,” she says.

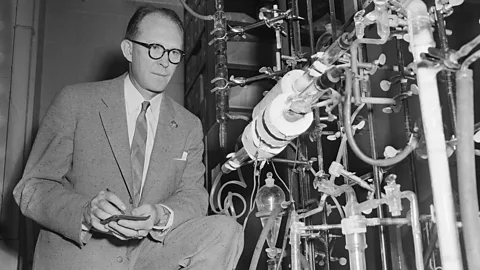

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe lab uses a device called an accelerator mass spectrometer to directly quantify the carbon-14 atoms in a sample – unlike Libby, who was only able to measure the radiation emitted and thereby infer how much carbon-14 a sample contained. The accelerator can also date tiny samples, in some cases a single milligram, whereas Libby needed much more material.

Removing carbon-containing contaminants can take weeks, but once done the accelerator readily spits out a sample’s estimated age. “It’s really exciting to be able to see the results immediately,” says Wood.

Source link