The threat of increased rates is real, but good policy can bring lower prices as demand grows.

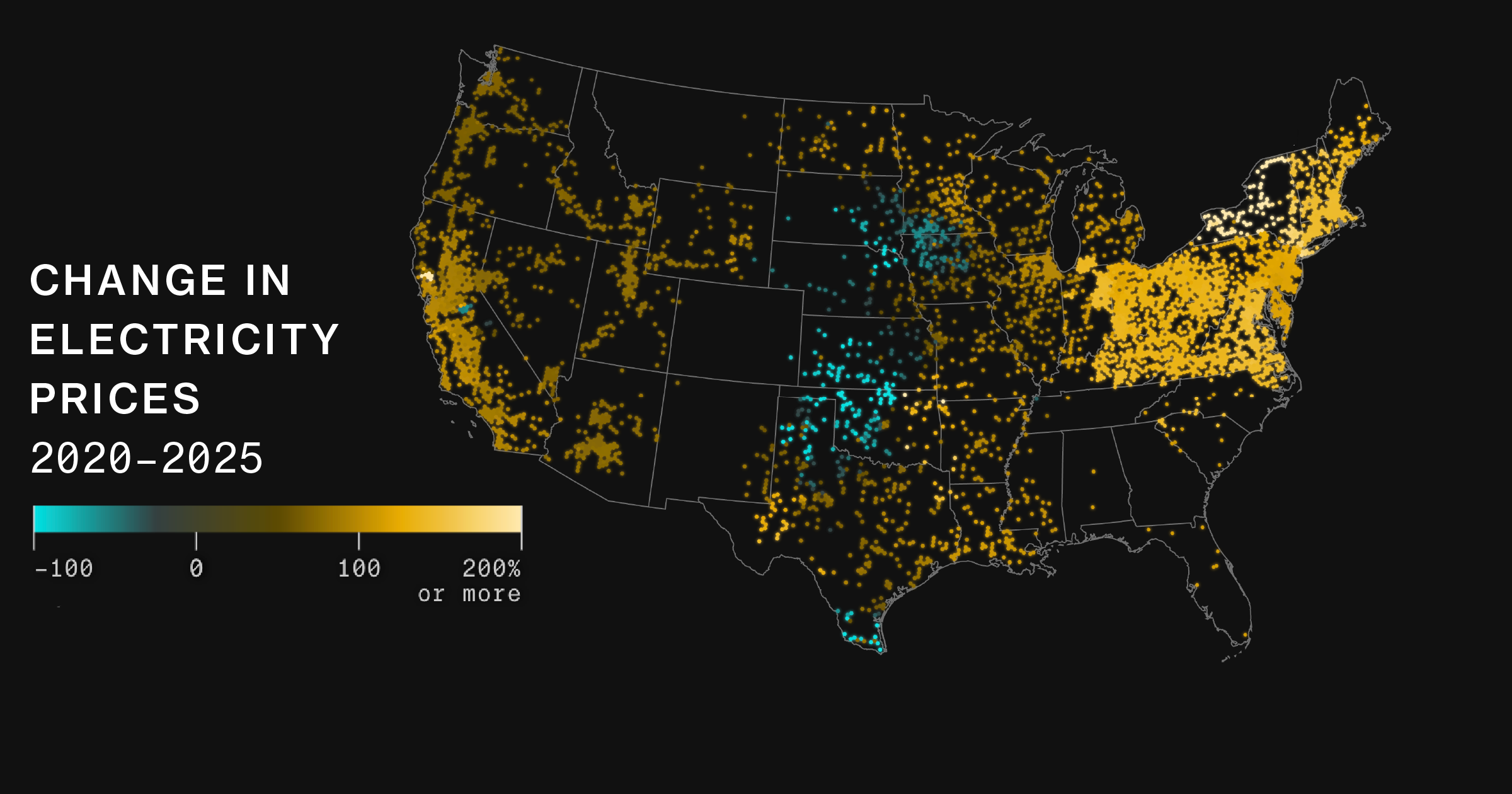

Electricity has recently replaced eggs, beef, and gasoline as the inflation concern du jour. Reporters looking for a new angle on rising prices have grabbed onto recent BLS data of escalating electricity rates. More complete data from the Energy Information Administration indicate that, outside of California, rates had been rising in line with inflation until a few months ago, but have since accelerated. Reports of recent utility rate requests also suggest that we may be at an inflexion point towards rate increases that outrun other consumer prices.

News reports of these increases invariably point to burgeoning artificial intelligence (AI) electricity demand as a major culprit. There is some truth to this narrative, but articles on it typically offer either muddled explanation of the link, or none at all. And there is much more to the relationship between demand growth from AI data centers and your electricity rates than has gotten coverage. So, today I want to explore the broader story of what an AI electricity demand boom could do to retail bills.

(Source) Data centers in Virginia, home to over one-third of worldwide hyperscale data centers.

—

The half-empty data center cost glass

As anyone reading this blog knows, data centers for AI use a lot of electricity. Both the software and the hardware are getting more efficient, but for at least the near term, it seems very likely that the growing use of AI will outrun efficiency improvements. That can increase retail prices in two ways.

First, demand growth can strain generation (and occasionally transmission) capacity, pushing up wholesale prices. Just as gentrifying neighborhoods raise rents for long-time residents, this new power demand boosts prices for all buyers in the energy market. If a retail electric supplier has locked down long-term contracts, then its customers are less exposed to the scarcity, but most utilities and competitive retailers still buy much of their juice at short-term prices. And as they go into the market to sign new contracts, they are competing with all buyers, including large data centers.

This dynamic isn’t unique to electricity. Many industries experience price jumps when demand suddenly accelerates. Those higher prices typically attract new production capacity, which then creates downward price pressure. There is valid reason for concern about a short-term price spike, but also extensive evidence that supply will respond (if the government doesn’t block it and grid operators avoid delaying interconnections) and eventually drive prices down again.

(Source)

The second way in which data centers – or any other new large load – could drive up retail prices is if they induce utilities to make expensive grid infrastructure upgrades to accommodate the new facilities and then the data center doesn’t actually buy much, or any, electricity. That could happen because the new company goes bankrupt (as crypto miners may do), or the company gets a better deal from a different utility, or the company decides to co-locate its own generation with its data center. As I wrote late last year, just as in other industries, buyers of a critical input like electricity that requires enormous investment from the provider should be required to sign long-term purchase contracts. That will reduce the risk that other retail electricity customers will get stuck with the bill.

As many analysts have pointed out (including me), much of the additional costs imposed by new large loads can be eliminated if they ratchet down their demand from the grid at times when the system is strained. By flexing their demand this way, they can avoid the 1% or fewer of the hours each year when additional demand can drastically raise prices, and also reduce reliability.

(Source)

—

Or is the glass more than half full?

But the impact of data centers needn’t be all bad. In fact, I think that in the medium run new data center loads can lower our rates. That’s because there are a lot of electricity network fixed and public policy costs that can be spread over more kilowatt-hours, thereby lowering the markup a utility has to charge to cover those network costs. That’s why PG&E and other utilities are touting new data center customers as a pathway to reduced rates.

That outcome, however, is not guaranteed. It requires overcoming some natural tendencies of utilities and policymakers to burden ratepayers. First, utilities like to grow their load in order to justify additional capital expenditures (such as transmission and distribution infrastructure) on which they typically earn a generous rate of return. So they are often not that excited about – or may even actively resist – giving new, or existing, customers incentives to trim demand during peak hours. Regulators too often fall in line with the utilities, possibly because more complex pricing and incentive structures to encourage reduced peak-time consumption make their lives more complicated than simpler rates. Or possibly because they believe that such incentives don’t work – despite many studies showing that customers respond to peak pricing programs.

Second, because they seek load growth, utilities often want to offer a sweet deal to a new customer who can bring significant electricity demand. Lower pricing to these new buyers means that they are contributing less to cover the network fixed costs and thus not lowering rates as much for other customers. The problem is exacerbated when utilities compete with one another to attract new large loads to their service territories by offering discount pricing. Policymakers often support the local utility’s race-to-the-bottom price competition, because they hope the new customers will bring jobs and tax revenues, despite the fact that data centers bring few new jobs and some of those same policymakers are offering tax breaks as well.

—

Getting to demand-driven rate reductions

It’s clear that rapid data center demand growth can drive up retail rates for other customers, particularly in the near term. But it is also clear that this can be an opportunity to spread the fixed costs over more sales, costs that make up a substantial part of our bills. The key to making new data center electricity demand a benefit to other customers is to create incentives for these new loads to restrain their peak demand and to avoid discount pricing so the new loads significantly contribute to covering system fixed costs.

—

I am now posting suggested energy readings (and some political views) most weekdays on Bluesky @severinborenstein.bsky.social

Follow us on Bluesky and LinkedIn, and subscribe to our email list to keep up with future content and announcements.

Suggested citation: Borenstein, Severin. “What Will Data Centers Do To Your Electric Bill?” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, September 29, 2025, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2025/09/29/what-will-data-centers-do-to-your-electric-bill/

—

By default comments are displayed as anonymous, but if you are comfortable doing so, we encourage you to sign your comments.

Source link